After an unprecedented campaign to raise £9 million ($14.5 million) in 8 months, the British Library has reached its goal and is now the proud owner of the 7th century St. Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest book in Europe that is fully intact from covers to binding to sewing structure to vellum pages. It was the most ambitious and most successful fundraising campaign in the Library’s history, marshaling donations from the likes of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the British Library trusts, the Art Fund, the Garfield Weston Foundation, the Foyle Foundation, major individual donors and members of the public.

After an unprecedented campaign to raise £9 million ($14.5 million) in 8 months, the British Library has reached its goal and is now the proud owner of the 7th century St. Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest book in Europe that is fully intact from covers to binding to sewing structure to vellum pages. It was the most ambitious and most successful fundraising campaign in the Library’s history, marshaling donations from the likes of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the British Library trusts, the Art Fund, the Garfield Weston Foundation, the Foyle Foundation, major individual donors and members of the public.

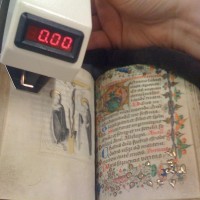

Although the former owners, the Society of Jesus, had loaned the book to the Library since 1979, since it wasn’t publicly owned the institution could not spend any money on conservation. It was on display, but with the cover closed to avoid any damage to the pages. Once the money to acquire the Gospel was secured, the British Library brought in leading conservation experts to assess the ancient volume. They found it in unbelievably good condition.

The Gospel has now gone on display in the entrance hall of the Sir John Ritblat Gallery in the British Library building at St. Pancras and for the first time it is open so that visitors can see two of the pages. This exhibit closes on June 17th.

The Gospel has now gone on display in the entrance hall of the Sir John Ritblat Gallery in the British Library building at St. Pancras and for the first time it is open so that visitors can see two of the pages. This exhibit closes on June 17th.

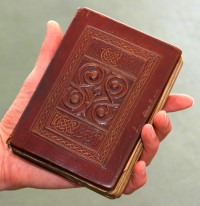

The St. Cuthbert Gospel is a copy of the Gospel of St. John written in Latin around 687 A.D., the year Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, died. The cover and back are made of crimson goatskin leather over birch boards, with a chalice and vine motif embossed on the front. It’s an incredibly rare surviving example of Anglo-Saxon leather work. Inside, the Latin script on the vellum pages is beautifully preserved and extremely clear.

It was written by monks at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, probably with the specific intention of creating a pocket gospel to place in Cuthbert’s coffin when it was moved behind the altar at Lindisfarne Cathedral in 698. When the coffin was opened, Cuthbert’s body was found to be incorrupt for the first, but not the last, time.

It was written by monks at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, probably with the specific intention of creating a pocket gospel to place in Cuthbert’s coffin when it was moved behind the altar at Lindisfarne Cathedral in 698. When the coffin was opened, Cuthbert’s body was found to be incorrupt for the first, but not the last, time.

The Vikings invaded Lindisfarne in 875, and the monks fled carrying the coffin and its precious cargo with them. They were on the lam for seven years until they settled in Durham. The saint was kept in a church on the site of the present Durham Cathedral (with occasional interludes elsewhere while escaping later invaders), then in Durham Cathedral as we know it today until Henry VIII’s marauders came to pillage the cathedral during the Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1541.

The monks hid St. Cuthbert’s body, but the Gospel was taken during this time and passed into private hands. It turned up again in 1769 when a private collector gave it to the English Jesuit College at Liège, later moved to England and renamed Stonyhurst College. The Jesuits kept it in the Stonyhurst Library until they loaned it permanently to the British Library in 1979.

Despite this checkered past, the St. Cuthbert Gospel has been preserved in a virtually incorrupt state of its own. You would never imagine looking at it that it’s 1300 years old. Now that the Library owns it, they are making long-term conservation plans to ensure that it retains its preternatural condition. They’ve also digitized the entire volume and uploaded it to their website.

The British Library is partnering with Durham Cathedral so the Gospel will split its time between London and Durham.

The Very Reverend Michael Sadgrove, Dean of Durham, said: “It is the best possible news to know that the Cuthbert Gospel has been saved for the nation. For the people of Durham and North East England, this is a most treasured book. Buried with Cuthbert and retrieved from his coffin, it held a place of great honour in Durham Cathedral Priory. The place in the Cathedral where it was kept in the Middle Ages is still the home of our unique manuscript collection.

“I want to pay tribute to the heroic efforts of the British Library in achieving this wonderful outcome. It has been a privilege to be associated with this fundraising campaign. I am pleased that the Friends of Durham Cathedral have supported it with a generous gift, and that one of the fund’s donors has chosen to channel a major gift through the Cathedral.

“As part of the plan agreed between the World Heritage Site and the British Library for its display, we look forward from time to time to welcoming this precious book back to the peninsula where Cuthbert’s remains are honoured. It will be always be loved and cherished here. I am sure Cuthbert shares our delight.”