Another sculpture that has been idling in a museum for ages is getting new attention all of a sudden. Egyptologist Giuseppina Capriotti of the Italian National Research Council believes a statue in the Cairo Museum depicts the twin children of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene. The sandstone statue was discovered near the temple of Hathor in Dendera on the west bank of the Nile in 1918. Cleopatra VII is known to have commissioned works in that temple, most famously a monumental pharaonic relief of herself and her son by Julius Caesar, Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, aka Cesarion.

Another sculpture that has been idling in a museum for ages is getting new attention all of a sudden. Egyptologist Giuseppina Capriotti of the Italian National Research Council believes a statue in the Cairo Museum depicts the twin children of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene. The sandstone statue was discovered near the temple of Hathor in Dendera on the west bank of the Nile in 1918. Cleopatra VII is known to have commissioned works in that temple, most famously a monumental pharaonic relief of herself and her son by Julius Caesar, Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, aka Cesarion.

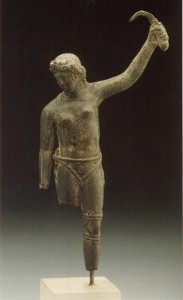

The Cairo Museum bought the five-foot-tall statue but didn’t pay it a great deal of attention, thinking it a representation of the twin gods Shu and Tefnet, son and daughter of the sun god Atum-Ra.

The statue is of two nude children, one male, one female, who bear the attributes of sun and moon respectively. They have an arm over each other’s shoulders while they hold a serpent in their other hands. The coils of two snakes wind around their legs and the base of the statue.

Capriotti noticed that the boy has a sun-disc on his head, while the girl boasts a crescent and a lunar disc. The serpents, perhaps two cobras, would also be different forms of sun and moon, she said. Both discs are decorated with the udjat-eye, also called the eye of Horus, a common symbol in Egyptian art.

“Unfortunately the faces are not well preserved, but we can see that the boy has curly hair and a braid on the right side of the head, typical of Egyptian children. The girl’s hair is arranged in a way similar to the so-called melonenfrisur (melon coiffure) an elaborated hairstyle often associated with the Ptolemaic dynasty, and Cleopatra particularly,” said Capriotti.

The statue dates to between 50 and 30 B.C. Mark Antony and Cleopatra’s twins were born in 40 B.C. so the timing fits, but it’s the unusual iconographic choices which suggest this is not just a statue of Shu and Tefnet. In the Egyptian pantheon, Tefnet, the sister, wears the solar disk, but in this piece the female twin wears the crescent moon and the male wears the sun, in keeping with the Greek tradition of the female moon goddess Selene and the male incarnation of the sun, Helios.

The twins’ embrace could suggest a solar eclipse, which is significant because when Mark Antony officially recognized the twins as his children three years after their birth, the event was marked by a solar eclipse. That’s when Cleopatra changed their names from plain Cleopatra and Alexander to Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios.

The twins’ embrace could suggest a solar eclipse, which is significant because when Mark Antony officially recognized the twins as his children three years after their birth, the event was marked by a solar eclipse. That’s when Cleopatra changed their names from plain Cleopatra and Alexander to Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios.

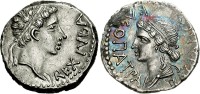

If these are Antony and Cleopatra’s twins, it’s the first representation of the two together ever discovered. The only other image we have is of an adult Cleopatra Selene on coins minted during her reign as Queen of Mauretania. Alexander Helios does not appear to have survived into adulthood, nor his younger brother Ptolemy Philadelphus.

After their parents’ suicides, all three of Antony’s children by Cleopatra were taken to Rome by Octavian in 30 B.C. to march in his triumph as royal captives in gold chains. He handed the three of them over to his sister Octavia, Antony’s third wife, to raise. The boys disappear from the historical record, perhaps dead at Augustus’ hand, perhaps from natural causes. Cleopatra Selene, on the other hand, was married around 20 B.C. to King Juba of Mauretania, a north African client state.

By all accounts she was an accomplished and powerful ruler, working alongside her husband and maybe even bossing him around a little. It’s not often you see coins with the king on the one side and the queen on the other. She even named her son Ptolemy, in keeping with her mother’s tradition rather than the more common practice of naming sons after their fathers, or at least including some reference to the paternal line.

By all accounts she was an accomplished and powerful ruler, working alongside her husband and maybe even bossing him around a little. It’s not often you see coins with the king on the one side and the queen on the other. She even named her son Ptolemy, in keeping with her mother’s tradition rather than the more common practice of naming sons after their fathers, or at least including some reference to the paternal line.