There’s a new exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles that explores medieval concepts of death and the afterlife via illuminations, printed works, stained glass and other visual arts. Heaven, Hell, and Dying Well: Images of Death in the Middle Ages runs from May 29 to August 12, and it makes extensive use of the Getty’s manuscript collection, including works which are not regularly on display.

Between plagues, famines, wars, and killer childbirth and infant mortality rates, death was an omnipresent theme in medieval art as in medieval life. Recurring allegories like “memento mori” (“remember thou art mortal”) and the “danse macabre” (“dance of death”) emphasized the inevitability and universality of death, which can strike anyone from any social class, at any age. Depicting what came after, an afterlife of bliss or eternal damnation, was an attempt to make sense of our terminally mortal condition and to encourage people to live and die well so they’d wind up in good eternity with God instead of the bad one with beaked millipede demons eating and excreting human souls.

Here, for instance, is the lovely Denise Poncher, an example of virtue and piety confronting death with serene acceptance.

Master of the Chronique scandaleuse (about 1493 – 1510), Denise Poncher before a Vision of Death, about 1500, Tempera colors, ink and gold on parchment, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 109, fol. 156.

It’s a page from The Office of the Dead, a Catholic prayer book that was commissioned particularly for Denise, probably on the occasion of her marriage. She’s wearing a red dress, on her knees before a particularly macabre representation of Death. He’s carrying four scythes and has already claimed three people. He’s striding callously over their dead bodies coming for Denise. Despite the rotting flesh sloughing off and the maggots writhing in and out of him, Denise is not scared. Her luminous white skin contrasts with Death’s decomposition. She knees with her prayer book in hand, soul shriven and ready for Heaven.

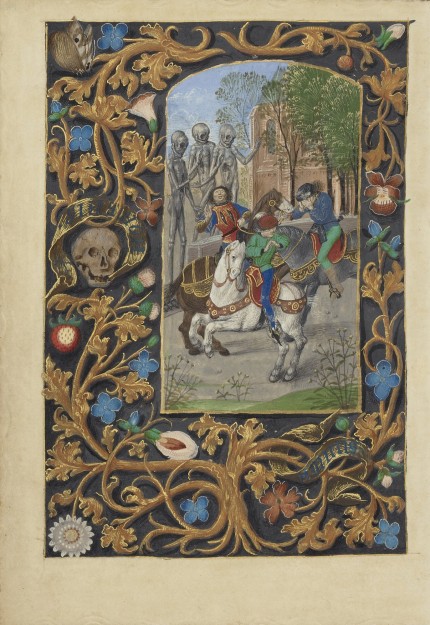

These three gents, on the other hand, are not so good an example.

Master of the Dresden Prayer Book or workshop (Flemish, active about 1480 – 1515) and Illuminator Unknown, The Three Living and the Three Dead, about 1480 – 1485?, Tempera colors and gold on parchment, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 23, fol. 146v.

This illumination depicts a well-known parable of the time: the Three Living and the Three Dead. As the story goes, three men on a boar hunt encounter three corpses. As the men reel back in shock, raise their hands in a last minute prayer, and cover their eyes in terror, the corpses identify themselves as their ancestors who have returned from the grave to admonish their descendants to change their ways before it’s too late. They must stop wasting their finite days playing games and spending lavishly on fine clothes and horses, and instead focus on the things that matter in life. “What you are, we were. What we are, you will be,” the corpses tell them, so live a humble, caring, pious life while you still can.

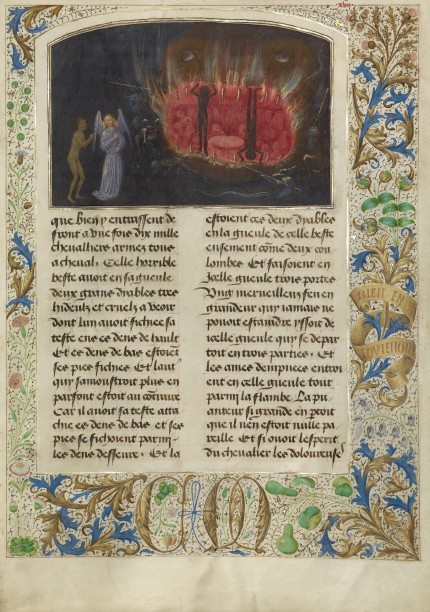

Then there’s The Visions of the Knight Tondal. Originally written by an Irish monk in the monastery at Regensburg in the 12th century, the story about an Irish knight who is taken on a journey through Heaven and Hell by his guardian angel was immensely popular in its day. It was translated into 15 languages dozens of times by the 15th century and may have inspired Dante’s later masterpiece, The Divine Comedy.

The Getty’s Tondal is a French edition from 1475 and it’s the only fully illuminated edition to survive. Made for Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy and her husband Charles the Bold, the text was done by David Aubert of Ghent and the 20 illuminations and elaborate border designs by Simon Marmion of Valenciennes.

The story begins with a narration describing the young and noble Lord Tondal who, the narrator tells us sadly, “was so confident in his youth, in his good looks, and in his strength, that to the salvation of his soul he never gave a thought.” He is in that very frame of mind at a feast when he suddenly falls unconscious. As his party guests freak out, Tondal’s guardian angel appears and takes his naked soul to Hell where he sees demons of terrifying grossness and briefly experiences the torture he will experience for all eternity unless he straightens up and flies right.

Simon Marmion (Flemish, active 1450 – 1489), The Beast Acheron from The Visions of the Knight Tondal, 1475, Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 30, fol. 17.

Next, the angel takes Tondal to Heaven, with a quick stop in a sort of limbo or purgatory where they encounter “the good but not very good.” After seeing the glories of Heaven which unlike the tortures of Hell he is allowed to observe from the outside but not participate in, Tondal resolves to change his life. He awakes and puts his Scrooge-like revelation into action, telling everyone he encounters about his experience and how they too must change and live lives of honest piety.

Take an interactive tour of Tondal’s story here or page through the entire book here. Click on any page to explore it in detail.

The Getty is holding lectures and talks in conjunction with the exhibition, but my favorite event hands down is the film series of Dante’s Inferno. On June 23, the Harold M. Williams Auditorium at the Getty Center will be showing two movies. The first is L’Inferno, a 1911 silent film that was the first Italian feature film ever made and an international blockbuster in its day. It took director Giuseppe de Liguoro three years to make. The special effects and set designs were revolutionary and even today many film experts consider it the greatest version of Dante’s work ever made.

That’s at 3:00. At 7:00 they’ll be showing Dante’s Inferno, an adaptation that uses hand-drawn paper puppets and miniature sets by artist Sandow Birk (who started the whole thing when he published a phenomenal update of The Divine Comedy) to bring Dante (voiced by Dermot Mulroney) and Virgil (voiced by James Cromwell) into the urban decay of modern Los Angeles.

That’s at 3:00. At 7:00 they’ll be showing Dante’s Inferno, an adaptation that uses hand-drawn paper puppets and miniature sets by artist Sandow Birk (who started the whole thing when he published a phenomenal update of The Divine Comedy) to bring Dante (voiced by Dermot Mulroney) and Virgil (voiced by James Cromwell) into the urban decay of modern Los Angeles.

I know it sounds crazy, but it’s brilliant and hilarious and if you can’t catch it at the Getty, watch it on Netflix or buy it from the website.