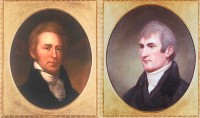

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent two years and three months working side by side, exploring the newly purchased Louisiana Territory and lands west, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. They kept extensive journals of their 1804-1806 expedition, documenting more than 200 plants and animals unknown to Western science and including no fewer than 140 maps of the vast region. They didn’t sign those copious notes, however.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent two years and three months working side by side, exploring the newly purchased Louisiana Territory and lands west, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. They kept extensive journals of their 1804-1806 expedition, documenting more than 200 plants and animals unknown to Western science and including no fewer than 140 maps of the vast region. They didn’t sign those copious notes, however.

Lewis’ autograph on its own is hard to find, despite his having been one of President Thomas Jefferson’s aides before the expedition and governor of the Louisiana Territory after. Clark served as agent of Indian affairs and general of the territorial militia during Lewis’ governorship. You’d think, therefore, that there would be at least some government documents, land grants or some such, signed by both men squirreled away in some institutional collection, but if there are, we don’t know of them. The Library of Congress doesn’t have any. The American Philosophical Society and Yale University who own some of the original journals don’t have any. Auction records going back 40 years have no record of a double Lewis and Clark autograph being sold.

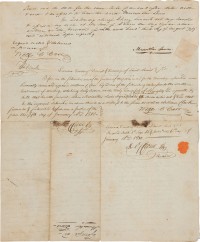

The only one we know of is an 1809 land indenture granting Jean Pierre Chouteau, a wealthy, influential French creole fur trader who was a personal friend of both Lewis and Clark, various properties in St. Louis for the sum of $4,355.50. It was signed by Meriwether Lewis as governor of the territory, with William Clark and lawyer William C. Carr as witnesses. This incredibly rare and historically significant document will go under the hammer at Heritage Auctions on June 9.

The only one we know of is an 1809 land indenture granting Jean Pierre Chouteau, a wealthy, influential French creole fur trader who was a personal friend of both Lewis and Clark, various properties in St. Louis for the sum of $4,355.50. It was signed by Meriwether Lewis as governor of the territory, with William Clark and lawyer William C. Carr as witnesses. This incredibly rare and historically significant document will go under the hammer at Heritage Auctions on June 9.

The combined autographs of Lewis and Clark aren’t the only thing that makes this document important. It was signed on August 3, 1809. Meriwether Lewis died under mysterious circumstances never fully explained on October 11, 1809. A month to the day after he signed Choteau’s land indenture, he left St. Louis on his way to Washington, D.C. to deal with some headaches arising from his questionable administrative choices. The territorial secretary, settlers and local political leaders had all complained to Washington about him and there were rumors that he had misused government funds. He was always slow to communicate with the Jefferson administration and particularly slow to deal with these kinds of allegations. Finally he was forced to deal with things when the federal government refused to pay War Department drafts he had drawn as governor of the Louisiana Territory.

On October 10, he stopped at an inn called Grinder’s Stand on the old Natchez Trace trail near what is today Hohenwald, Tennessee, 70 miles south of Nashville. The next morning before dawn, shots rang out. Servants found Lewis felled by multiple gunshots to his chest and head, including one that took off a chunk of his skull. He lived for a few more hours, dying just after the sun rose. Although nobody claimed to have witnessed the shooting, Lewis’ guide reported that he had committed suicide. The innkeeper’s wife Priscilla Grinder claimed she had seen Lewis behaving strangely the night before and to have observed him alone crawling back to his room after the gunshots woke her up.

It is generally accepted by scholars (and at the time by Thomas Jefferson and William Clark) that he committed suicide, but his family insisted that he was murdered. In any case, the death of Lewis fell so near to the signing of this indenture that William C. Carr, an original witness to the signing, was called upon a second time to attest to the document’s legality. The document was notarized on the verso on January 5, 1810, and reads: “Before me the Subscriber one of the Justices of the peace in and for the township aforesaid – Personally came and appeared William C. Carr Esqre one of the Subscribing witnesses to the within Instrument of writing , who being duly sworn on the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God deposeth & saith that he was present, when Meriwether Lewis signed & sealed & delivered the same as his act & Deed that he the deponent subscribed his name thereto as a witness to the Same as well as William Clark.”

Meriwether Lewis was buried on the spot, today milepost 385.9 of the Natchez Trace Parkway. There was no autopsy. The only doctor to ever examine the body did so in 1848 and he said it appeared Lewis had been murdered. Lewis’ family has been trying since 1993 to have the body exhumed, but the Natchez Trace Parkway is under the purview of the National Park Service, which as a point of policy prohibits exhumations unless the burial is in danger of being damaged by development, park activities or natural forces. As of its most recent ruling in 2010, the Department of the Interior is sticking with the policy and refusing to exhume Lewis’ body.