The same auction selling the document signed by both Lewis and Clark features an exceptional collection of Wild Westerniana. Heritage Auction’s Legends of the Wild West Signature sale lives up to its name, offering objects, pictures and assorted ephemera from some of the most iconic figures of the American West.

One of them is Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, the vain, fearless cavalry commander who fought with distinction for the Union during the Civil War and with considerably less distinction in the Indian Wars. From the days of his earliest commands in the Civil War, Custer made a name for himself — usually not a good one — with his flashy look. He eschewed the standard uniform, creating customized clothing (buckskin jacket, red neckerchief) and gear (pearl-handled Webley revolvers) that came to define him and his men as they adopted elements of his style.

One of them is Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, the vain, fearless cavalry commander who fought with distinction for the Union during the Civil War and with considerably less distinction in the Indian Wars. From the days of his earliest commands in the Civil War, Custer made a name for himself — usually not a good one — with his flashy look. He eschewed the standard uniform, creating customized clothing (buckskin jacket, red neckerchief) and gear (pearl-handled Webley revolvers) that came to define him and his men as they adopted elements of his style.

It’s one of those custom pieces that is now for sale: a personal cavalry saddle he had made to his specification and used during the Indian Wars. The cavalry used the McClellan saddle, invented by General George McClellan and adopted by the War Department in 1859; however, Custer wanted to include convenient features from the Western saddle, so he had a saddler modify the cavalry-issue to his specifications. He added a saddle horn, leather covered stirrups and elaborate decoration fit for the dandy he was.

The saddle remained in the Custer family until 1941 when it was purchased by collector Lawrence Frost, so whoever buys it will be only twice removed from the original owner, in addition to having a direct connection to his butt.

Custer died in the disastrous Battle of Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876 fighting the Sioux and Cheyenne, among them the warriors of Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man and chief Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull had been fighting the encroaching United States forces for years before Custer and the 7th Cavalry met their end at Little Bighorn. The Sioux and Cheyenne’s famous victory on that day turned out to be Pyrrhic because it resulted in the US military sending thousands more troops to hunt them down over the next year. Sitting Bull and his band refused to surrender and escaped to Canada in 1877. Their living conditions in Saskatchewan were deplorable.

Finally in 1881, cold and hunger drove them back across the border where they surrendered to the Army detachment at Fort Buford in Dakota Territory. Sitting Bull spent the next two years as a prisoner of war before the US authorities allowed him and his people to move to the Standing Rock Reservation in what is now North Dakota. When they arrived at Standing Rock on May 10, 1883, Buffalo Bill Cody was rehearsing his first Wild West in Omaha, Nebraska. As soon as he heard that Sitting Bull was (sort of) free, Buffalo Bill began to campaign for him to join his show.

Finally in 1881, cold and hunger drove them back across the border where they surrendered to the Army detachment at Fort Buford in Dakota Territory. Sitting Bull spent the next two years as a prisoner of war before the US authorities allowed him and his people to move to the Standing Rock Reservation in what is now North Dakota. When they arrived at Standing Rock on May 10, 1883, Buffalo Bill Cody was rehearsing his first Wild West in Omaha, Nebraska. As soon as he heard that Sitting Bull was (sort of) free, Buffalo Bill began to campaign for him to join his show.

Standing Rock Indian agent James McLaughlin had other ideas. He wanted to use Sitting Bull for his own profit. McLaughlin put together a show of his own, the “The Sitting Bull Combination,” and toured with the chief, some of his friends, their wives and an interpreter. Part of the show was a speech by Sitting Bull. He would talk about his people’s dire living conditions, then the interpreter would spin a lurid tale about the killing of Custer at Little Bighorn which had nothing even remotely to do with anything Sitting Bull had actually said. (Sitting Bull wasn’t even on the battlefield at Little Bighorn. He was in charge of non-combatant defense.)

The Secretary of the Interior was not amused. He made McLaughlin dissolve the troupe, leaving a void for Buffalo Bill to step into. On June 6, 1885, Sitting Bull and John M. Burke (proxy for Buffalo Bill and his partner Nate Salsbury) signed a contract for the chief to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. It was a good deal. Sitting Bull and ten of his people got paid well for four months of work. Sitting Bull made $50 per week, two weeks in advance, plus a $125 signing bonus, plus travel expenses to and from Standing Rock. In an addendum to the contract, Sitting Bull also got sole rights to selling his pictures and autographs, a highly lucrative side deal. The money he made touring with Buffalo Bill supported his people for the rest of the year.

The Secretary of the Interior was not amused. He made McLaughlin dissolve the troupe, leaving a void for Buffalo Bill to step into. On June 6, 1885, Sitting Bull and John M. Burke (proxy for Buffalo Bill and his partner Nate Salsbury) signed a contract for the chief to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. It was a good deal. Sitting Bull and ten of his people got paid well for four months of work. Sitting Bull made $50 per week, two weeks in advance, plus a $125 signing bonus, plus travel expenses to and from Standing Rock. In an addendum to the contract, Sitting Bull also got sole rights to selling his pictures and autographs, a highly lucrative side deal. The money he made touring with Buffalo Bill supported his people for the rest of the year.

That contract is now up for auction. Because of the addendum to that contract, Sitting Bull sold hundreds of signed pictures and postcards. His signature just by itself is not impossibly rare. His signature on a contract, on the other hand, is not just rare but unique. He never signed a treaty with the US government. This contract marks his entry into the legend of the Wild West as Buffalo Bill wrote it.

Petite but deadly sharpshooter Annie Oakley became part of that legend thanks to Buffalo Bill, even though she was born and raised in Ohio and never stepped foot out west until she went on tour with Cody. In fact, her skills were so remarkable that she was integrated into the mythology both literally and figuratively. When Sitting Bull was in St. Paul doing one of McLaughlin’s shows before he signed that contract with Buffalo Bill, he saw Annie Oakley’s sharpshooting act and was so impressed that he asked to meet her. They got along so well that he adopted her according to Lakota custom, giving her the name “Little Sure Shot.” Annie took the honor seriously, used the name from that day forward and truly considered Sitting Bull her adopted father.

There are all kinds of Annie Oakley memorabilia available for sale in this auction. Some relatives of hers are selling a wonderful group of pictures, weapons, letters and my personal favorite: a Stetson hat that is the only western style hat of hers known to survive. It’s beautiful even just as a vintage piece, but it’s downright dreamy given that it once adorned Annie’s wee head.

There are all kinds of Annie Oakley memorabilia available for sale in this auction. Some relatives of hers are selling a wonderful group of pictures, weapons, letters and my personal favorite: a Stetson hat that is the only western style hat of hers known to survive. It’s beautiful even just as a vintage piece, but it’s downright dreamy given that it once adorned Annie’s wee head.

Thanks to Thomas Alva Edison, we actually have footage of Annie doing her thing. In 1884, three years after the first demonstrations of the kinetograph, Edison’s first moving picture recorder, he asked Annie to come to his studio in West Orange so he could film her high speed shooting with the kinetograph. He wanted to test his machine for accuracy, to see if it could capture the smoke from her gun. It did.

That spring, Annie’s quick decimation of glass targets became one of the first movies shown to the public in kinetoscope parlors.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eAmnQvMHlRs&w=430]

As for Buffalo Bill himself, he is represented in the auction by a single lot that is filled with gems. The star of the lot is a Civil War-issue Remington New Model Army .44 percussion revolver Cody used during his years slaughtering buffalo and as a guide for the Army during the Indian Wars. He gave it to his best friend Charles Trego and his wife Carrie for Christmas in 1906. In the accompanying note (also included in the lot) he wrote: “To Charlie & Carrie Trego. This old Remington revolver. I carried and used for many years in Indian Wars and Buffalo killing. And it never failed me.”

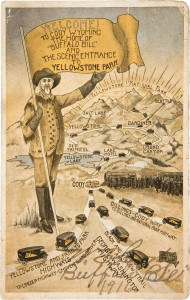

Its unsavory murderous associations keeps it from being my favorite piece of the varied lot, though. A humble postcard from just before Bill’s death takes that honor. It’s a bird’s eye view of Cody, Wyoming and the entrance to Yellowstone National Park. Buffalo Bill signed and dated it in 1916, a historically significant date for three reasons: 1) it’s the year before Bill Cody’s death and 2) it’s the year after Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane first authorized private cars to enter Yellowstone. The postcard is promoting the town of Cody as a the apex of three great driving routes leading to Yellowstone and cars, flagged as coming from all over the country, especially the northeast, feature prominently in the scene. The train with its vast shadowy passenger masses is secondary to the cars and the individual freedom they provide to drive through Yellowstone and points beyond.

Its unsavory murderous associations keeps it from being my favorite piece of the varied lot, though. A humble postcard from just before Bill’s death takes that honor. It’s a bird’s eye view of Cody, Wyoming and the entrance to Yellowstone National Park. Buffalo Bill signed and dated it in 1916, a historically significant date for three reasons: 1) it’s the year before Bill Cody’s death and 2) it’s the year after Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane first authorized private cars to enter Yellowstone. The postcard is promoting the town of Cody as a the apex of three great driving routes leading to Yellowstone and cars, flagged as coming from all over the country, especially the northeast, feature prominently in the scene. The train with its vast shadowy passenger masses is secondary to the cars and the individual freedom they provide to drive through Yellowstone and points beyond.

Lastly, 1916 was an election year pitting Republican candidate Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes against the Democratic incumbent President Woodrow Wilson. On the back of the postcard, Bill Cody wrote an election joke to Charles Trego: “Hughes can’t ride Woodrow he is pulling leather already and will be disqualified.” Pulling leather is a term to describe when a bronco rider is forced to touch his saddle with his free hand, a disqualifying error. So Woodrow Wilson was the metaphoric bucking bronco in this scenario, and he was throwing Hughes so off-balance that he was forced to touch the saddle and thus knock himself out of the running.

Lastly, 1916 was an election year pitting Republican candidate Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes against the Democratic incumbent President Woodrow Wilson. On the back of the postcard, Bill Cody wrote an election joke to Charles Trego: “Hughes can’t ride Woodrow he is pulling leather already and will be disqualified.” Pulling leather is a term to describe when a bronco rider is forced to touch his saddle with his free hand, a disqualifying error. So Woodrow Wilson was the metaphoric bucking bronco in this scenario, and he was throwing Hughes so off-balance that he was forced to touch the saddle and thus knock himself out of the running.

I love that so much. If that postcard were separated out from the lot of expensive things like the revolver, I would totally have bid for it.