The Toledo Museum of Art has owned the Etruscan black-figure kalpis, a large ceramic vase used for holding water, for 30 years, the last 11 of them while under investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations division (HSI) and the Italian government. Despite evidence that the kalpis had been looted, smuggled and sold to the museum with (poorly) forged documentation, the Toledo institution fought the law, holding out longer than wealthier and more prestigious museums like the Getty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Now the law has finally won, and still kicking and screaming, the Toledo Museum of Art has grumpily agreed to return the vase to Italy.

The Toledo Museum of Art has owned the Etruscan black-figure kalpis, a large ceramic vase used for holding water, for 30 years, the last 11 of them while under investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations division (HSI) and the Italian government. Despite evidence that the kalpis had been looted, smuggled and sold to the museum with (poorly) forged documentation, the Toledo institution fought the law, holding out longer than wealthier and more prestigious museums like the Getty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Now the law has finally won, and still kicking and screaming, the Toledo Museum of Art has grumpily agreed to return the vase to Italy.

This sordid tale of beauty, greed, lust, deception, fraud and willful blindness begins at the end of the 6th century B.C., around 510-500 B.C., in the Etruscan city-state of Vulci. Vulci was an important political and artistic center 50 miles northwest of Rome, famous as the birthplace of the legendary sixth king of Rome, Servius Tullius (reigned 578-535 B.C.), and as the likely location for the workshop of an artist known to us today solely as the Micali Painter.

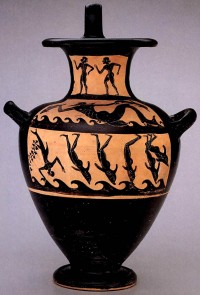

The Micali Painter made black-figure pottery, a style imported from Greece in the 7th century B.C. Figures are painted with a clay slip on fresh clay vessels. When fired, the painted areas turn black and contrast with the native red of the clay. Micali was the most prolific Etruscan artist of the genre, and he made the style his own rather than just copying Greek artists. His work is in the world’s top museums.

Vulci was defeated by Roman consul Tiberius Coruncanius in 280 B.C. Rome cut off Vulci’s access to the sea and, cut off from the maritime trade that had sustained it, the city declined and died. No new town was built over it. All that is left of Vulci today are some ruins and a massive underground necropolis with tens of thousands of tombs; many of them remain unrecorded and unexplored.

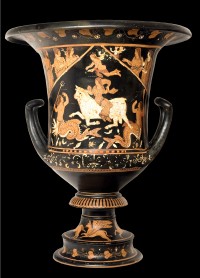

That makes Vulci prime territory for the depredations of the tombaroli, tomb robbers who stick spikes in the ground searching for undocumented tombs. When they find one, they strip it of everything they find, from vases to jewels to the frescoes on the wall and mosaics on the floor. Often they destroy the tomb itself on the way out to cover up their tracks. They then sell the treasures they’ve ripped from the ground to middlemen and “art dealers” like the infamous Giacomo Medici for ridiculously small sums. Just to give you an idea of what I’m talking about, the tombarolo who in the mid-1970s looted the Asteas krater, a large red-figure vase used for mixing water and wine painted with the Rape of Europa in the 4th century B.C. by Greek master Asteas, sold it for $1,533 and a suckling pig. True story. The dealers who bought it from him sold it to the Getty in 1981 for $275,000. The Getty was forced to return the krater to Italy in 2005.

That makes Vulci prime territory for the depredations of the tombaroli, tomb robbers who stick spikes in the ground searching for undocumented tombs. When they find one, they strip it of everything they find, from vases to jewels to the frescoes on the wall and mosaics on the floor. Often they destroy the tomb itself on the way out to cover up their tracks. They then sell the treasures they’ve ripped from the ground to middlemen and “art dealers” like the infamous Giacomo Medici for ridiculously small sums. Just to give you an idea of what I’m talking about, the tombarolo who in the mid-1970s looted the Asteas krater, a large red-figure vase used for mixing water and wine painted with the Rape of Europa in the 4th century B.C. by Greek master Asteas, sold it for $1,533 and a suckling pig. True story. The dealers who bought it from him sold it to the Getty in 1981 for $275,000. The Getty was forced to return the krater to Italy in 2005.

Sometime before 1981, tombaroli found a black-figure Etruscan kalpis by the Micali Painter depicting a scene from the life of Dionysus wherein the god of wine and drama punishes the pirates who try to kidnap him for ransom or to sell him into slavery by turning them into dolphins as they dive into the sea to flee his wrath, a story immortalized in a Homeric hymn. It’s a unique and beautiful piece. It’s more than 20 inches in height and has three handles. The pirates are captured mid-transformation, with the legs of men but the heads and fins of dolphins and with the tails and fins of dolphins but the heads of men. The tombaroli sold the water jug to Giacomo Medici, who in turn sold it to dealers Gianfranco and Ursula Becchina.

In 1982, the Becchinas sold it to the Toledo Museum of Art for a modest price of $90,000. The only documentation they provided the museum of the kalpis’ collection history prior to their purchase of it was a photocopy of a declaration signed by deceased Swiss collector Karl Haug claiming decades of ownership. The Becchinas said they purchased the vessel from Haug’s son who provided them with the document ostensibly written by his father.

In two paragraphs typed in German on the stationery of the Haug-owned Hotel Helvetia in Basel, Switzerland, Haug stated to whom it may concern that he had owned the vessel since 1935, conveniently preceding the passage of the 1939 Italian law declaring all antiquities property of the Italian state unless the possessor can prove ownership prior to 1902. Still, even that made-up date was well after a 1909 law that required all antiquities to be declared to customs for proper licensing and taxation. Haug made no such declaration, so even if it were true that he had bought it in 1935, it still would have been illegally smuggled out of the country.

Whatever rudimentary due diligence Toledo did to confirm that the photocopy of the typewritten “Swiss collector” claim wasn’t a blatant and obvious fraud, it didn’t extend to checking with the Italian authorities for evidence of legal export. You’d think that would be step one, unless, of course, looking the other way was standard operating practice for museums at this time. (Spoiler: it was.) Besides, the Metropolitan Museum of Art also wanted the vase, and Toledo wanted badly to beat them to the punch.

Of course Haug’s story wasn’t true at all. It wasn’t even written by Haug. The facade began to crack in 1995 when a warehouse in Freeport, Switzerland owned by Giacomo Medici was raided by the Italian Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale unit (a.k.a., the Art Police), as well as Swiss and British police forces. They found thousands of artifacts, some of them still encrusted with dirt from their recent excavation, plus files and Polaroids documenting past sales. One of the Polaroids was of an Etruscan three-handled black-figure kalpis depicting Dionysus turning the Tyrrhenian pirates into dolphins. The kalpis in the picture was muddy, as was the picture itself. Now, I don’t know exactly what model of Polaroid took that picture, but it was certainly produced long after 1935.

Of course Haug’s story wasn’t true at all. It wasn’t even written by Haug. The facade began to crack in 1995 when a warehouse in Freeport, Switzerland owned by Giacomo Medici was raided by the Italian Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale unit (a.k.a., the Art Police), as well as Swiss and British police forces. They found thousands of artifacts, some of them still encrusted with dirt from their recent excavation, plus files and Polaroids documenting past sales. One of the Polaroids was of an Etruscan three-handled black-figure kalpis depicting Dionysus turning the Tyrrhenian pirates into dolphins. The kalpis in the picture was muddy, as was the picture itself. Now, I don’t know exactly what model of Polaroid took that picture, but it was certainly produced long after 1935.

Medici was formally arrested in 1997 and the slow wheels of Italian justice began to grind their way towards a trial. Meanwhile, in 2000 the Toledo Museum of Art, still fearing no legal repercussions, sent the kalpis to Venice so it could be a part of the seminal exhibit of Etruscan artifacts at the Palazzo Grassi. “Gli Etruschi” ran from November 2000 to July 2001 and was a smash hit, exhibiting an unprecedented vast collection of Etruscan objects loaned from museums all over Italy and the world. The vase was still on display in Venice when the Museum received a subpoena in 2001 from the assistant U.S. Attorney in Toledo asking for its documentation of the kalpis.

Doubtless fearing that Italy, which had initiated the U.S. Attorney’s investigation, might confiscate the kalpis while it was still on Italian soil, the museum sent a registrar to Venice to bring it back pronto. Thus began the decade-long battle.

More evidence of the looting, smuggling and fraud was discovered when the contents of the Becchinas’ warehouses in Basel were seized by the Swiss police on February 23, 2002. Again they found thousands of artifacts, photographs and documents exposing decades of theft barely covered up by half-assed forgeries like the Haug document. In the Becchina archives was yet another Polaroid of the kalpis, caked in mud from its recent excavation. There were also stacks of blank documents on Hotel Helvetia letterhead, rubber-stamped and ready to be filled in with whatever “Swiss private collection” fantasy the Becchinas wished to concoct.

In 2004 Giacomo Medici was convicted on multiple counts of receiving stolen archaeological artifacts illegally removed from Italy. One of those archaeological artifacts he was convicted of fencing was the Dionysus kalpis. Confronted with a legal decision from an Italian court that the vase had been looted and smuggled out of Italy at most a few years before the museum’s purchase of it, the Toledo museum director said that if the object had been stolen they’d return it. They just wanted a little more proof, is all.

The Polaroids, the paper trail in the Becchina archives, even Ursula’s confession to how they routinely forged Haug collection histories using rubber-stamped blanks were not apparently sufficient. A single flimsy photocopy of Haug’s so-called statement was more than sufficient proof of legitimacy for them to buy the piece, but piles of evidence accumulated over years of painstaking investigation and even a conviction in a court of law weren’t enough to convince them their precious was ill-gotten gain. They would keep dancing this “more evidence” dance for another seven years.

In April 2010, Immigration and Customs Enforcement sent an agent to the museum to yet again discuss the return of the kalpis. Between November 2010 and January of 2012, ICE three times warned the museum that if they wouldn’t hand over the vase, agents would have to confiscate it. Museum director Brian Kennedy told the Toledo Blade these were “threats” and that it felt like the museum was the victim of a “drug bust.” They kept holding out for more proof, for more time to establish a cultural exchange with Italy (meaning they wanted Italy to give them something else on long-term loan to fill the hole in their collection the kalpis would leave).

Finally in March of this year, the Toledo Museum of Art was satisfied that they had been provided sufficient evidence of what everyone has known for a decade. They agreed to return the kalpis. On June 7, United States Homeland Security Investigations “constructively seized” the vase (you can read their case filed in district court here), allowing it to stay on the museum premises for security reasons until a formal return ceremony later in the year. The U.S. Attorney’s Office and ICE released statements applauding “the integrity of the Toledo Museum of Art for their willingness to ensure that this piece is repatriated to its home country” and claiming this long, strange ride as “an example of our office, ICE HSI and the Toledo Museum of Art working collaboratively to return this artifact to its rightful place,” statements which look a little silly given the museum’s sour grapes in the Toledo Blade article from four days ago, but oh well. At least the kalpis is finally on the way home.