A teratoma, for those of you who have not delved into the fascinating world of medical oddities, is a tumor, usually benign, in which abnormal germ cells cause random bits of body to grow inside organs that bear no relation to said bits. Teratomas have been found to contain hair, teeth, bone, skin, muscle, bronchi, fatty cells, thyroid tissue, and more. These are not parasitic twins or fetus in fetu situations. Early in embryonic development, germ cells are triggered by our genes to form sperm in males and eggs in females, but they are also pluripotent meaning they have the potential to develop through cellular differentiation into any cell type. Sometimes they get triggered abnormally, and a creepy little ball of teeth and hair winds up setting up shop in your ovaries, among other places.

It’s a fairly rare phenomenon and in 60% of cases patients are entirely asymptomatic so teratomas aren’t often encountered even among the living. They are virtually unheard of in the archaeological record because they have to calcify to survive the march of time, and once calcified they can be easily confused for simple stones by archaeologists who have no idea there’s lung tissue and teeth and hair inside that rock. It takes a special teratoma to calcify and be positioned in such a way that it is clearly identifiable as a mass of organic origin.

This special teratoma was found in the pelvic region of a woman who died and was buried in early 5th century Spain. Her skeletal remains were discovered in 2010 in a necropolis at the archeological site of La Fogonussa near the town of Lleida in Catalonia, Spain. She was 30 to 40 years old when she died and was buried under roof tiles (tegulae) that had been leaned against each other to form a gabled roof over her body, a common form of burial at the time. There were no grave goods found interred with her; she was likely of modest means.

This special teratoma was found in the pelvic region of a woman who died and was buried in early 5th century Spain. Her skeletal remains were discovered in 2010 in a necropolis at the archeological site of La Fogonussa near the town of Lleida in Catalonia, Spain. She was 30 to 40 years old when she died and was buried under roof tiles (tegulae) that had been leaned against each other to form a gabled roof over her body, a common form of burial at the time. There were no grave goods found interred with her; she was likely of modest means.

Physically she wasn’t in great shape. She had degenerative lesions from arthritis in her shoulder, wrist, hip, and knee and arthritic bone spurs in her spine. Then there was the round ball in her pelvis. Its position and shape strongly suggested that it was calcified organic material so it was sent to the lab for further analysis. There were all kinds of possible candidates: it could have been a large gallstone, a calcified lymph nodes, an ovarian calcification, even a coproliths (calcified feces). Researchers examined it visually and with CT scans to figure out what it was.

Physically she wasn’t in great shape. She had degenerative lesions from arthritis in her shoulder, wrist, hip, and knee and arthritic bone spurs in her spine. Then there was the round ball in her pelvis. Its position and shape strongly suggested that it was calcified organic material so it was sent to the lab for further analysis. There were all kinds of possible candidates: it could have been a large gallstone, a calcified lymph nodes, an ovarian calcification, even a coproliths (calcified feces). Researchers examined it visually and with CT scans to figure out what it was.

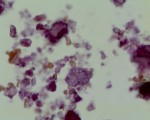

They found that it’s a partial sphere 42.72 millimeters (1.68 inches) in length and 44.27 millimeters (1.74 inches) in diameter at its widest point. It’s not a solid mass anymore. Most of the tissue has decayed leaving a shell 3.2 millimeters (.13 inches) thick at the thickest. That shell was once the capsule or outer layer of the tumor. There was some loose sediment inside the shell in which researchers found a thin piece of bone and two deformed teeth. An irregular bone formation attached to the inner wall also proved to contain teratoma treasure: two more deformed teeth.

They found that it’s a partial sphere 42.72 millimeters (1.68 inches) in length and 44.27 millimeters (1.74 inches) in diameter at its widest point. It’s not a solid mass anymore. Most of the tissue has decayed leaving a shell 3.2 millimeters (.13 inches) thick at the thickest. That shell was once the capsule or outer layer of the tumor. There was some loose sediment inside the shell in which researchers found a thin piece of bone and two deformed teeth. An irregular bone formation attached to the inner wall also proved to contain teratoma treasure: two more deformed teeth.

The teeth and bone prove that it’s no gallstone, but rather the only archaeological ovarian teratoma ever discovered. Only one other ancient teratoma has been reported in the paleopathological literature, an 1800-year-old mediastinic (above the pericardium but below the collarbone) teratoma published in 2009 by none other than Philippe Charlier, who between the teratoma, the 16th century royal mistress overdosing on gold, the head of Henry IV, the blood of Louis XVI and the ancient pooper scoopers, has had one mighty cool career.

The teeth and bone prove that it’s no gallstone, but rather the only archaeological ovarian teratoma ever discovered. Only one other ancient teratoma has been reported in the paleopathological literature, an 1800-year-old mediastinic (above the pericardium but below the collarbone) teratoma published in 2009 by none other than Philippe Charlier, who between the teratoma, the 16th century royal mistress overdosing on gold, the head of Henry IV, the blood of Louis XVI and the ancient pooper scoopers, has had one mighty cool career.

Researchers were not able to determine teratoma lady’s cause of death. Encapsulated ovarian teratomas are benign and not fatal in and of themselves, but they can cause complications that result in death.

“This ovarian teratoma could have been the cause of this woman’s death, because sometimes the development of teratomas results in displacement and functional disturbances of adjacent organs,” the researchers write. They note that infection, hemolytic anemia and pregnancy complications can also occur with an ovarian teratoma, events that could also have caused the woman’s death.

Or not. She could just as easily have died from a heart attack or a hundred other illnesses that can’t be identified from skeletal remains. Since the teratoma is small and was safely ensconced in her ovary, it wouldn’t have shown outwardly. She probably didn’t know she had a mass inside her, never mind a mass of teeth and bones.

Or not. She could just as easily have died from a heart attack or a hundred other illnesses that can’t be identified from skeletal remains. Since the teratoma is small and was safely ensconced in her ovary, it wouldn’t have shown outwardly. She probably didn’t know she had a mass inside her, never mind a mass of teeth and bones.