On Sunday May 17th, 2009, three-year-old James Hyatt, his father and grandfather were exploring a field in Hockley, Essex. James went first, using his grandfather’s metal detector. After five minutes of scanning, the machine alerted.

On Sunday May 17th, 2009, three-year-old James Hyatt, his father and grandfather were exploring a field in Hockley, Essex. James went first, using his grandfather’s metal detector. After five minutes of scanning, the machine alerted.

“It went beep, beep, beep. Then we dug into the mud. There was gold there,” James, now four, said.

“We didn’t have a map. Only pirates use treasure maps,” he stated.

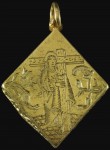

James is indeed wise in the way of treasure. After digging down eight inches into the soil, they pulled out an engraved locket which turned out to be reliquary from the early 1500s. As a gold object more than 300 years old, the locket was declared official treasure trove under the terms of the 1996 Treasure Act at a coroner’s inquest.

When it made the news in late 2010, there was much excited speculation that the discovery was so rare it could be worth millions of pounds. It is rare — one of only four similar pieces known — but the market value turned out to be considerably lower. The British Museum acquired it for £70,000 ($110,000) and the sum was split between the Hyatt family and the owner of the land on which the locket was found. In terms of history, however, it’s a million dollar discovery which is why it’s now on display in the British Museum’s Medieval Europe gallery.

When it made the news in late 2010, there was much excited speculation that the discovery was so rare it could be worth millions of pounds. It is rare — one of only four similar pieces known — but the market value turned out to be considerably lower. The British Museum acquired it for £70,000 ($110,000) and the sum was split between the Hyatt family and the owner of the land on which the locket was found. In terms of history, however, it’s a million dollar discovery which is why it’s now on display in the British Museum’s Medieval Europe gallery.

The diamond-shaped pendant is engraved on the front with the image of a female saint, probably Saint Helena, mother of Constantine, holding the cross. Dashes along the length and width of the cross are meant to indicate wood grain. The saint stands on a checkerboard pattern tile floor while on either side of her and the cross are floral tendrils.

On the back side is a veritable shower of blood droplets falling out of and over four incisions and a cut heart symbolizing the five wounds of Christ. That back piece is actually a panel that slides out along grooves cut into the sides. Inside would have been kept a small relic. Given the imagery on the pendant, the contents were probably thought to be a piece of the True Cross which according to legend Saint Helena found on her trip to the Holy Land from 326 to 328 A.D. Helena is often depicted holding the cross because of her famous finds.

On the back side is a veritable shower of blood droplets falling out of and over four incisions and a cut heart symbolizing the five wounds of Christ. That back piece is actually a panel that slides out along grooves cut into the sides. Inside would have been kept a small relic. Given the imagery on the pendant, the contents were probably thought to be a piece of the True Cross which according to legend Saint Helena found on her trip to the Holy Land from 326 to 328 A.D. Helena is often depicted holding the cross because of her famous finds.

The back didn’t open when the reliquary was first found. The bottom was damaged, pressed inwards so it was derailed from its guide grooves. Marilyn Hockey, Head of Metals Conservation in the British Museum’s Department of Conservation and Scientific Research was able to correct this by painstakingly prying the back up from the bottom working under a microscope to lift the panel with a miniature probe.

When the back finally slid out, conservators found (drumroll) a few flax fibers locally grown. Sorry, no piece of the True Cross. Examination of the fibers with a scanning electron microscope identified fragments of the outer stems of flax. These are unprocessed and would not be present if the flax fibers were from threads of linen fabric. They’re root hairs, basically, which could well have gotten in there during the pendant’s sojourn underground.

When the back finally slid out, conservators found (drumroll) a few flax fibers locally grown. Sorry, no piece of the True Cross. Examination of the fibers with a scanning electron microscope identified fragments of the outer stems of flax. These are unprocessed and would not be present if the flax fibers were from threads of linen fabric. They’re root hairs, basically, which could well have gotten in there during the pendant’s sojourn underground.

On three sides of the of the pendant are inscribed the names of the Three Wise Men — Iaspar (Caspar), Melcior (Melchiore), Baltasar (Balthazar) — in a lovely Lombardic script. The fourth side has a floral tendril similar to the ones on either side of Helena.

The pendant is 1 inch wide and 1.3 inches long which makes its rich decoration even more unusual and difficult to produce. Experts believe the engravings were likely enameled when the piece was new. That would have given the object a rich combination of colors on top of the precious metal, a popular style in late Medieval jewelry. Only a very wealthy person could have afforded to buy such an expensive symbol of their pious dedication to the blood and wounds of Christ.