Last summer, the Philadelphia Museum of Art announced a major restoration project to clean, conserve and regild the statue of Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that graces the top of the museum’s Great Stair Hall. The 13-foot statue of the Huntress drawing her bow was made in 1893 to top the tower of architect Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden. Standing on one foot on a spherical base, Diana was originally a weather vane, turning with the wind atop her tower; only later was she riveted to her base for her own safety. She was the tallest point in the city in her day, and shone so brightly that she could be seen from New Jersey.

Last summer, the Philadelphia Museum of Art announced a major restoration project to clean, conserve and regild the statue of Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that graces the top of the museum’s Great Stair Hall. The 13-foot statue of the Huntress drawing her bow was made in 1893 to top the tower of architect Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden. Standing on one foot on a spherical base, Diana was originally a weather vane, turning with the wind atop her tower; only later was she riveted to her base for her own safety. She was the tallest point in the city in her day, and shone so brightly that she could be seen from New Jersey.

Sadly, her fate was tied to that of the building which was demolished in 1925 to make way for the New York Life Insurance Building. New York Life put her in storage hoping she would find a new home in the city, but every attempt to keep her in New York failed and in 1932 she was adopted by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

(New York did come to regret its callous rejection of its once-iconic golden lady. In 1967, with the city in the process of building the fourth and last iteration of Madison Square Garden over the graveyard of yet another demolished Beaux Arts masterpiece, the original Penn Station, New York mayor John Lindsay asked Philadelphia mayor James Tate if they could have Diana back to put her inside the new Garden. Tate declined, pointing out that “when no one wanted this poor little orphan girl, Philadelphia took her in, gave her a palatial home and created a beautiful image for her with a worldwide reputation.”)

(New York did come to regret its callous rejection of its once-iconic golden lady. In 1967, with the city in the process of building the fourth and last iteration of Madison Square Garden over the graveyard of yet another demolished Beaux Arts masterpiece, the original Penn Station, New York mayor John Lindsay asked Philadelphia mayor James Tate if they could have Diana back to put her inside the new Garden. Tate declined, pointing out that “when no one wanted this poor little orphan girl, Philadelphia took her in, gave her a palatial home and created a beautiful image for her with a worldwide reputation.”)

After three decades exposed to the elements and seven years in storage, Diana needed some work when she got to Philadelphia. She was in decent condition overall, but her surface was darkened by corrosion and everything but a few traces of the original gilding was gone. In the midst of the Great Depression, the museum had neither the means nor the inclination to regild her. Decades later, in the mid-1980s, the museum did consider regilding Diana, but the time and funding wasn’t there. There was no immediate conservation need since the statue was structurally sound.

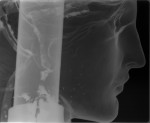

Thanks to the financial support of Bank of America’s Global Art Conservation Project, in 2013 Diana finally got a full makeover. The focus of the project was first and foremost to analyze and document the statue’s surface and structure. The armature, including the weather vane mechanism which still exists inside the spherical base, was examined for condition and to learn more about how Diana was built. Traces of gilding were examined by a scanning electron microscope to determine the exact composition and color of the original gold. The whole statue was X-rayed and subjected to ultrasonic thickness testing to assess the condition of the molded copper sheets Saint-Gaudens soldered and riveted together.

Thanks to the financial support of Bank of America’s Global Art Conservation Project, in 2013 Diana finally got a full makeover. The focus of the project was first and foremost to analyze and document the statue’s surface and structure. The armature, including the weather vane mechanism which still exists inside the spherical base, was examined for condition and to learn more about how Diana was built. Traces of gilding were examined by a scanning electron microscope to determine the exact composition and color of the original gold. The whole statue was X-rayed and subjected to ultrasonic thickness testing to assess the condition of the molded copper sheets Saint-Gaudens soldered and riveted together.

One the initial observations and tests were complete, conservators cleaned the corrosion, revealing the lovely copper color and the joins. The statue was then primed with a corrosion inhibiting paint containing zinc chromate which left the surface an alarming canary yellow. Thankfully that phase didn’t last long. The statue was then painstakingly covered with 180 square feet of 23.4-karat red gold leaf. Because Saint-Gaudens disliked the use of very bright gold at eye level, the gilding was toned down to match his original intent.

One the initial observations and tests were complete, conservators cleaned the corrosion, revealing the lovely copper color and the joins. The statue was then primed with a corrosion inhibiting paint containing zinc chromate which left the surface an alarming canary yellow. Thankfully that phase didn’t last long. The statue was then painstakingly covered with 180 square feet of 23.4-karat red gold leaf. Because Saint-Gaudens disliked the use of very bright gold at eye level, the gilding was toned down to match his original intent.

The process took five months. In November, the scaffolding came down and Diana was revealed in her freshly gilded splendor. Behold the shiny:

Visitors to the museum during the restoration got to observe it happening in real time, and the whole process was filmed and shown on screens in the museum. The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s conservation page has two videos illustrating the restoration process. I hope many more will follow because those two are straight awesome.

Visitors to the museum during the restoration got to observe it happening in real time, and the whole process was filmed and shown on screens in the museum. The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s conservation page has two videos illustrating the restoration process. I hope many more will follow because those two are straight awesome.

In this one you see conservators sampling traces of the original gilding, doing cleaning tests before removing the corrosion over the whole statue, doing a boroscopic (self-lit remote camera) examination of interior, opening the ball and removing the bow and arrow.

This video features the steam cleaning done after the acidic cleanser removed the corrosion, the X-ray imaging and ultrasonic thickness testing, and the scanning electron microscope analysis of the gold traces.