A skeleton kept in an old wooden box in the basement of Philadelphia’s Penn Museum has regained his history, and what an illustrious one it is. Curator of the museum’s Physical Anthropology Section Dr. Janet Monge knew the skeleton was there, one of 2,000 complete skeletons in the collection, but it had no catalog card or any other identifying marks. It might have remained a mystery skeleton forever had it not been for one of my favorite things: an ambitious digitization project.

A skeleton kept in an old wooden box in the basement of Philadelphia’s Penn Museum has regained his history, and what an illustrious one it is. Curator of the museum’s Physical Anthropology Section Dr. Janet Monge knew the skeleton was there, one of 2,000 complete skeletons in the collection, but it had no catalog card or any other identifying marks. It might have remained a mystery skeleton forever had it not been for one of my favorite things: an ambitious digitization project.

In 2012, the Penn Museum and the British Museum embarked on a collaborative mission to digitize all the artifacts, photographs, archives, maps, notes and other documents from Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations of Ur, now in southern Iraq, from 1922 and 1934. The 12 years of excavations were joint expeditions of the British Museum and the Penn Museum. As was common archaeological practice at the time, half of what they unearthed remained in country, while the other half was split evenly between the two institutions. Funded with a $1.28 million grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, Ur of the Chaldees: A Virtual Vision of Woolley’s Excavations will digitally reunite all the products of these seminal digs and make high resolution images of every pot fragment, cuneiform tablet, archaeological layer map, bull-headed lyre, etc. available for free in an online database.

In 2012, the Penn Museum and the British Museum embarked on a collaborative mission to digitize all the artifacts, photographs, archives, maps, notes and other documents from Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations of Ur, now in southern Iraq, from 1922 and 1934. The 12 years of excavations were joint expeditions of the British Museum and the Penn Museum. As was common archaeological practice at the time, half of what they unearthed remained in country, while the other half was split evenly between the two institutions. Funded with a $1.28 million grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, Ur of the Chaldees: A Virtual Vision of Woolley’s Excavations will digitally reunite all the products of these seminal digs and make high resolution images of every pot fragment, cuneiform tablet, archaeological layer map, bull-headed lyre, etc. available for free in an online database.

Dr. William Hafford, Penn Museum’s Ur Digitization Project Manager, encountered in the course of his work some division lists recording which items were sent to Philadelphia and which to London. It was the list for the 1929-1930 dig season (a fateful season during which Katharine Woolley invited Agatha Christie to visit the dig where she met her future husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan) that caught his eye.

Dr. William Hafford, Penn Museum’s Ur Digitization Project Manager, encountered in the course of his work some division lists recording which items were sent to Philadelphia and which to London. It was the list for the 1929-1930 dig season (a fateful season during which Katharine Woolley invited Agatha Christie to visit the dig where she met her future husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan) that caught his eye.

It said that the Penn Museum would receive, among other items, one tray of “mud of the flood” and two “skeletons.” Further research into the Museum’s object record database indicated that one of those skeletons, 31-17-404, deemed “pre-flood” and found in a stretched position, was recorded as “Not Accounted For” as of 1990.

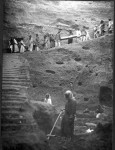

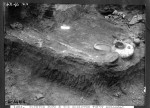

Exploring the extensive records Woolley kept, Hafford was able to find additional information and images of the missing skeleton, including Woolley himself painstakingly removing an Ubaid skeleton intact, covering it in wax, bolstering it on a piece of wood, and lifting it out using a burlap sling. When he queried Dr. Monge about it, she had no record of such a skeleton in her basement storage—but noted that there was a “mystery” skeleton in a box.

When the box was opened later that day, it was clear that this was the same skeleton in Woolley’s field records, preserved and now reunited with its history.

The fact that he’s garnered the nickname “Noah” is a hint of that history. The skeleton is 6,500 years old, 2,000 years older than the remains found in the more glamorous Royal Cemetery of Ur. Woolley found it in Pit F, a trench he dug 50 feet deep under the surface of the archaeological site of Ur. When he reached 40 feet down, he countered a thick layer of water-lain silt that became known as the “flood layer.” This was the find that provided evidence of a great flood, not the world-destroying flood that would thousands of years later be described in the Biblical story of Noah, but a major local disaster that submerged Ur when it was an island surrounded by marshes. People regrouped after the flood, rebuilding Ur and burying their dead, but the story of the flood became legend and was incorporated in literature like the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The fact that he’s garnered the nickname “Noah” is a hint of that history. The skeleton is 6,500 years old, 2,000 years older than the remains found in the more glamorous Royal Cemetery of Ur. Woolley found it in Pit F, a trench he dug 50 feet deep under the surface of the archaeological site of Ur. When he reached 40 feet down, he countered a thick layer of water-lain silt that became known as the “flood layer.” This was the find that provided evidence of a great flood, not the world-destroying flood that would thousands of years later be described in the Biblical story of Noah, but a major local disaster that submerged Ur when it was an island surrounded by marshes. People regrouped after the flood, rebuilding Ur and burying their dead, but the story of the flood became legend and was incorporated in literature like the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Woolley kept digging underneath the flood layer and found 48 graves from the Ubaid period (5,500 B.C. to 4,000 B.C.). The Penn skeleton had been buried with ten pottery vessels at his feet in a grave dug into the silt, which indicates he had survived the flood.

Woolley kept digging underneath the flood layer and found 48 graves from the Ubaid period (5,500 B.C. to 4,000 B.C.). The Penn skeleton had been buried with ten pottery vessels at his feet in a grave dug into the silt, which indicates he had survived the flood.

Thanks to Woolley’s conscientious method of excavation and preservation — coating the skeleton and the soil around it  in wax then covering it in plaster of Paris to keep it safe during the journey — Noah will be a great boon to research on this early period of Ur. Modern technology may be able to reveal much about his life, diet, health, perhaps cause of death, maybe even some DNA given the good condition of his teeth. Not much is known about the Ubaid period, so this research could fill in a great many blanks. And let’s not forget the silt. Archaeologists are learning amazing things from context soil nowadays.

in wax then covering it in plaster of Paris to keep it safe during the journey — Noah will be a great boon to research on this early period of Ur. Modern technology may be able to reveal much about his life, diet, health, perhaps cause of death, maybe even some DNA given the good condition of his teeth. Not much is known about the Ubaid period, so this research could fill in a great many blanks. And let’s not forget the silt. Archaeologists are learning amazing things from context soil nowadays.