The village of Slocum in Anderson County, east Texas, was a relatively well-off farming community founded by emancipated slaves after the Civil War. It was small but well-appointed, with a school, two churches, a store and a post office, all black owned and operated. On July 29th, 1910, that all came to an end when a mob of hundreds of white men descended on the town and gunned down every resident they could find. While the official list of the dead is eight people, those are only the ones who can be confirmed today. The real tally will likely never be known. Whoever wasn’t killed ran for their lives to other towns in Texas or up North (hopefully not to Tulsa or East St. Louis or Chicago), forced to leave their property behind to be stolen by the murderers.

Information on the events as they unfolded over the two ensuing days of mayhem was chaotic and confused. Slocum was an isolated town and the mob had cut many of the phone lines before the attack to ensure their targets were as helpless as possible. The stories that were able to make it into the press came from the perpetrators. They claimed a white farmer had shot a black man who owed him money, spurring the black population of Slocum to take up arms and go full Nat Turner on the white people in surrounding communities. Nothing gets a good white mob going better than rumors of a black insurrection, and it doesn’t have to be true to work. Other stories circulating involved an unpaid debt that resulted in the black debtor insulting the white creditor, and a lynching in a nearby town fomenting revolt among the black people of Slocum.

Information on the events as they unfolded over the two ensuing days of mayhem was chaotic and confused. Slocum was an isolated town and the mob had cut many of the phone lines before the attack to ensure their targets were as helpless as possible. The stories that were able to make it into the press came from the perpetrators. They claimed a white farmer had shot a black man who owed him money, spurring the black population of Slocum to take up arms and go full Nat Turner on the white people in surrounding communities. Nothing gets a good white mob going better than rumors of a black insurrection, and it doesn’t have to be true to work. Other stories circulating involved an unpaid debt that resulted in the black debtor insulting the white creditor, and a lynching in a nearby town fomenting revolt among the black people of Slocum.

The source of much of this deadly chatter was likely a prominent white man named Jim Spurger who was angry when African American Abe Wilson was put in charge of a road improvement project that Spurger wanted for himself. A witness would later tell a grand jury that Spurger claimed he’d been “threatened and outraged until it had become unbearable”. Whatever the cause, the white avengers assembled and started shooting.

Even within a single article there were vastly differing reports, see this story in the July 31st The Abilene Daily Reporter so charmingly subtitled “Whites Gathered Arms and Went Coon Hunting.” The headline declares “23 Negroes, 4 Whites Dead,” but in the very first paragraph the figures change to “two white men and fifteen negroes have already been killed,” and when the story continues on page six, the numbers change again, dropping to zero in the case of white fatalities.

According to official statements made here tonight 18 negroes are known to be dead as a result of the race riots which occurred during the day and the number will likely be increased to 25, and a dozen more injured. It is not known definitely that any white men have been killed, but several have been injured.

No white men were killed. It wasn’t a “battle” or “race riot.” It was a premeditated massacre. Here’s how Anderson County Sheriff William Black, who was on the scene, described what was going on as quoted in an August 1st, 1910, New York Times article (pdf):

“Men were going about killing negroes as fast as they could find them, and so far as I was able to ascertain, without any real cause. These negroes have done no wrong that I could discover. There was just a hot-headed gang hunting them down and killing them. I don’t know how many there were in the mob, but I think there must have been 200 or 300. Some of them cut the telephone wires. They hunted the negroes down like sheep.”

Texas Rangers and state militia were deployed to restore order. District Judge B.H. Gardner ordered all area saloons closed (the mob was very thoroughly liquored up, to nobody’s surprise) and prohibited the sale of firearms or ammunition. By then most of the black residents were hiding in the swamps or safely out of town, so there weren’t many targets left. At the end of the first week in August, 16 white men, including James Spurger, and six black men were held in jail without bail. At least one of those black men was Jack Holley who had fled to Palestine, the county seat, when the violence engulfed Slocum killing one son and wounding another and asked to be jailed for his own protection.

Texas Rangers and state militia were deployed to restore order. District Judge B.H. Gardner ordered all area saloons closed (the mob was very thoroughly liquored up, to nobody’s surprise) and prohibited the sale of firearms or ammunition. By then most of the black residents were hiding in the swamps or safely out of town, so there weren’t many targets left. At the end of the first week in August, 16 white men, including James Spurger, and six black men were held in jail without bail. At least one of those black men was Jack Holley who had fled to Palestine, the county seat, when the violence engulfed Slocum killing one son and wounding another and asked to be jailed for his own protection.

Gardner convened a grand jury and gave them these extraordinary instructions:

“All of you are white men, and all of you are Southern men, and it is your duty now to investigate the killing and murder of a large number of Negroes, say at least eight and possibly 10 or 12 or more, who have been killed in the southeastern part of your county by men of your color. I regard this affair as the most damaging that could happen in this county: That it is a disgrace, not only to the county, but to the state, and it is up to this jury to do its full duty.”

He subpoenaed virtually the entire town of Slocum. When some of the so-called leading white citizens refused to testify, Gardner had them arrested. Some black witnesses returned to town to give testimony only to mysteriously disappear again before they could take the stand. On August 17th, seven men, Jim Spurger among them, were indicted on 22 counts of murder. The cases were moved to Harris County for trial and that’s when things fell into the usual Jim Crow template: the defendants were released on bail and nobody was ever tried. Gardner and Black were voted out of office in the next elections.

Black residents never returned to Slocum. Their property was confiscated by various “legal” means (liens, sale of abandoned property for non-payment of taxes) and extralegal (just taking it) and people like Jack Holley, who had owned a store, a dairy and 300 acres of prime farmland, moved to Palestine without a dime and died a pauper. His family changed the spelling of their name to Hollie out of fear of reprisals, a perfectly reasonable fear when you consider that Gardner who was a) white and b) a judge, was violently assaulted by Spurger six years later.

The history of the massacre was covered up, ignored in text books and by the local historical society. People told the old stories in private, however. For years one of Jack Holley’s descendants, Constance Hollie-Ramirez, worked with other descendants of the victims to pull this ugly history out of the shadows into the light. Her father and uncle had tried to get a historical marker in the 1980s, but the chairman of the Anderson County historical commission, Jimmy Ray Odom, rejected their petition saying that “It was mislabeled a massacre. A massacre is when you kill hundreds of people.”

Hollie-Ramirez picked up where her parents left off and in 2011 the Texas Legislature passed a resolution (pdf) officially acknowledging the Slocum Massacre. Prospects for a historical marker picked up steam in 2014 with the publication of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas by Fort Worth journalist E. R. Bills. Hollie-Ramirez and Bills applied to the county for a roadside historical marker to commemorate the victims of the massacre. They were rejected. Anderson County Commissioner Greg Chapin wrote: “Without further evidence of legal documentation, or the facts of guilty parties taken (sic) responsibility for the incident, Anderson County cannot support the marker.”

So they went over the county’s head and applied directly to the Texas State Historical Association in Austin. Again the county historical commissioned was in opposition. Apparently not clear on how historical markers work, Odom wrote to state officials, “The citizens of Slocum today had absolutely nothing to do with what happened over a hundred years ago. This is a nice, quiet community with a wonderful school system. It would be a shame to mark them as racist from now until the end of time.” A wonderful school system with some painfully glaring omissions in their history texts, that is, and evidently by design.

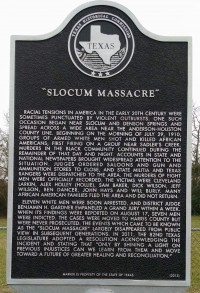

The application for a marker was approved last January after getting an exceptionally high rating of 98 out a possible 100 points. On Saturday, January 16th, 2015, Constance Hollie-Ramirez joined other descendants of the victims, author E. R. Bills and even Jimmy Ray Odom at the unveiling of the roadside marker commemorating the Slocum Massacre.