The Duomo of Monza has antecedants dating to the 6th century when the Lombards ruled swaths of Italy. Monza, in the northern Italian region of Lombardy, was the summer residence of the Lombard Queen Theodelinda (c. 570-628). In 595 she had a chapel dedicated to John the Baptist built next to her royal palace in Monza. In the 13th century a new church was built on the remains of Theodelinda’s chapel. It was rebuilt again in the early 14th century and expanded significantly at the end of the century. Two chapels were added in the expansion, one dedicated to the Virgin Mary and another across from it on the north side of the cathedral transept dedicated to Queen Theodelinda. She got such high billing because she converted her first husband King Authari to Catholic Christianity and after his death, she converted her second husband King Agilulf first to Christianity and then to Catholicism. Arianism was predominant among Lombards at the time, so Theodelinda was instrumental in establishing a foundation of Nicene Christianity among the Lombards.

The Duomo of Monza has antecedants dating to the 6th century when the Lombards ruled swaths of Italy. Monza, in the northern Italian region of Lombardy, was the summer residence of the Lombard Queen Theodelinda (c. 570-628). In 595 she had a chapel dedicated to John the Baptist built next to her royal palace in Monza. In the 13th century a new church was built on the remains of Theodelinda’s chapel. It was rebuilt again in the early 14th century and expanded significantly at the end of the century. Two chapels were added in the expansion, one dedicated to the Virgin Mary and another across from it on the north side of the cathedral transept dedicated to Queen Theodelinda. She got such high billing because she converted her first husband King Authari to Catholic Christianity and after his death, she converted her second husband King Agilulf first to Christianity and then to Catholicism. Arianism was predominant among Lombards at the time, so Theodelinda was instrumental in establishing a foundation of Nicene Christianity among the Lombards.

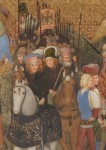

The vault of the Theodelinda Chapel was painted with figures of saints and evangelists in the 1430s. In 1441, the Zavattari family of Milan were commissioned to decorate the chapel walls with a series of frescoes depicting scenes from the life of the Lombard queen. Pater familias Franceschino, who worked for decades on the stained glass windows of the Duomo of Milan, and his sons Giovanni and Gregorio painted 45 scenes on five levels from the floor to the vaulted ceiling. They used a variety of media — egg tempera, oil tempera, dry painting, fresco, stucco relief, gilding — showcasing the Zavattari’s workshop experience in diverse art forms.

The vault of the Theodelinda Chapel was painted with figures of saints and evangelists in the 1430s. In 1441, the Zavattari family of Milan were commissioned to decorate the chapel walls with a series of frescoes depicting scenes from the life of the Lombard queen. Pater familias Franceschino, who worked for decades on the stained glass windows of the Duomo of Milan, and his sons Giovanni and Gregorio painted 45 scenes on five levels from the floor to the vaulted ceiling. They used a variety of media — egg tempera, oil tempera, dry painting, fresco, stucco relief, gilding — showcasing the Zavattari’s workshop experience in diverse art forms.

The result was a massive masterpiece covering 5,400 square feet of wall space. It is considered by many to be the greatest example of the International Gothic style espoused by artists like Carlo Crivelli. Also like Crivelli, the Zavattari used gesso decorative elements to create dimension and relief and then gilded them. In fact there is gold everywhere. The skies aren’t blue; they’re gold. The crowns, the jewels, the hair, the helmets, the clothes, the musical instruments, the tables, the goblets, the spurs, the scepters, the reliquaries, the crosses, the candelabra, the candles, the horses’ manes, architectural elements are all gilded. Little wonder that it’s been nicknamed “the Sistine Chapel of the North.”

The result was a massive masterpiece covering 5,400 square feet of wall space. It is considered by many to be the greatest example of the International Gothic style espoused by artists like Carlo Crivelli. Also like Crivelli, the Zavattari used gesso decorative elements to create dimension and relief and then gilded them. In fact there is gold everywhere. The skies aren’t blue; they’re gold. The crowns, the jewels, the hair, the helmets, the clothes, the musical instruments, the tables, the goblets, the spurs, the scepters, the reliquaries, the crosses, the candelabra, the candles, the horses’ manes, architectural elements are all gilded. Little wonder that it’s been nicknamed “the Sistine Chapel of the North.”

The scenes of Theodelinda’s life story were taken from 8th century monk Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards (the parts about Theodelinda start here) and from 13th century historian Bonincontro Morigia’s Chronicle of Monza. The first 23 cover the meeting and marriage of Theodelinda and Authari. Scenes 24 to 30 depict her second marriage to Agilulf. In scenes 31 to 41 are the founding of the church, the death of Agilulf and of Theodelinda. The last scenes depict Byzantine Emperor Constans II’s failed attack on the Lombards of southern Italy and his return to Byzantium with his tail between his legs.

The scenes of Theodelinda’s life story were taken from 8th century monk Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards (the parts about Theodelinda start here) and from 13th century historian Bonincontro Morigia’s Chronicle of Monza. The first 23 cover the meeting and marriage of Theodelinda and Authari. Scenes 24 to 30 depict her second marriage to Agilulf. In scenes 31 to 41 are the founding of the church, the death of Agilulf and of Theodelinda. The last scenes depict Byzantine Emperor Constans II’s failed attack on the Lombards of southern Italy and his return to Byzantium with his tail between his legs.

In keeping with the standard practice of the time, the style of dress is typical of the courts of 15th century northern Italy. The frescoes are replete with scenes of courtly life — hunts, banquets, balls, parties — and provide a uniquely rich window into the attire, hairstyles, weapons and armour of the 15th century Milanese court. There are no fewer than 28 scenes dedicated to weddings or preparation for weddings. This is thought to be a symbolic reference to the marriage of Bianca Maria Visconti, legitimized natural daughter and sole heir of Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, to Francesco Sforza. Theodelinda had chosen her second husband thereby making him king. Bianca’s marriage to Francesco ultimately transferred the dukedom of Milan from the Visconti to the Sforza family after her father’s death. They were married in 1441, the same year the Zavattari were commissioned to paint the chapel, probably by Filippo Maria Visconti.

In keeping with the standard practice of the time, the style of dress is typical of the courts of 15th century northern Italy. The frescoes are replete with scenes of courtly life — hunts, banquets, balls, parties — and provide a uniquely rich window into the attire, hairstyles, weapons and armour of the 15th century Milanese court. There are no fewer than 28 scenes dedicated to weddings or preparation for weddings. This is thought to be a symbolic reference to the marriage of Bianca Maria Visconti, legitimized natural daughter and sole heir of Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, to Francesco Sforza. Theodelinda had chosen her second husband thereby making him king. Bianca’s marriage to Francesco ultimately transferred the dukedom of Milan from the Visconti to the Sforza family after her father’s death. They were married in 1441, the same year the Zavattari were commissioned to paint the chapel, probably by Filippo Maria Visconti.

The chapel frescoes were repeatedly restored between the 17th and 19th centuries. During World War II, the walls were protected from bomb damage using sandbags, which had the unfortunate unintended consequence of increasing the moisture and salt levels inside the chapel. Those earlier restorations became increasingly unstable and the paint and stucco cracked and flaked. By 2007, the condition of the masterpiece was dire. Paint was lifting off and significant areas had suffered permanent losses.

The chapel frescoes were repeatedly restored between the 17th and 19th centuries. During World War II, the walls were protected from bomb damage using sandbags, which had the unfortunate unintended consequence of increasing the moisture and salt levels inside the chapel. Those earlier restorations became increasingly unstable and the paint and stucco cracked and flaked. By 2007, the condition of the masterpiece was dire. Paint was lifting off and significant areas had suffered permanent losses.

The World Monuments Fund, the Region of Lombardy, the Fondazione Gaiani (the organization in charge of preserving the Duomo of Milan) and other private foundations, began a three million euro restoration project in 2008. The latest technology — lasers, nanotech, imaging — combined with traditional arts to revive details lost for centuries, like a delicate damask pattern that had morphed into a dark block and reflections of red wine on the inside of a gold chalice. Areas of loss were filled in using organic paints without acrylic that can easily be removed with a wet sponge. “A favor for future restorers,” as project leader Anna Lucchini put it. A new lighting system was also installed to make the frescoes more easily seen by visitors on the ground. The restoration took seven years.

The World Monuments Fund, the Region of Lombardy, the Fondazione Gaiani (the organization in charge of preserving the Duomo of Milan) and other private foundations, began a three million euro restoration project in 2008. The latest technology — lasers, nanotech, imaging — combined with traditional arts to revive details lost for centuries, like a delicate damask pattern that had morphed into a dark block and reflections of red wine on the inside of a gold chalice. Areas of loss were filled in using organic paints without acrylic that can easily be removed with a wet sponge. “A favor for future restorers,” as project leader Anna Lucchini put it. A new lighting system was also installed to make the frescoes more easily seen by visitors on the ground. The restoration took seven years.

The newly refreshed frescoes were officially reopened to the public in a ceremony on October 16th, 2015.