The latest and greatest DNA technology has revealed the origins of some of the 80 men buried in a Roman-era cemetery in York. The burials have intrigued and mystified archaeologists since they were first discovered under the garden of an 18th century mansion on Driffield Terrace in 2004. Of the

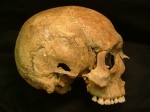

The latest and greatest DNA technology has revealed the origins of some of the 80 men buried in a Roman-era cemetery in York. The burials have intrigued and mystified archaeologists since they were first discovered under the garden of an 18th century mansion on Driffield Terrace in 2004. Of the  80 individuals, 48 of them, 60% of the total and 79% of the 61 skeletons with surviving crania and cervical vertebrae, had been decapitated from behind with a very sharp, very fine blade. Their heads were buried with them but not in anatomically correct or even consistent positions. Skulls were placed on the chest, between the legs and at their feet.

80 individuals, 48 of them, 60% of the total and 79% of the 61 skeletons with surviving crania and cervical vertebrae, had been decapitated from behind with a very sharp, very fine blade. Their heads were buried with them but not in anatomically correct or even consistent positions. Skulls were placed on the chest, between the legs and at their feet.

Decapitated remains have been found in Roman cemeteries before, but very few. One study tallied 98 decapitations making up 6% of the inhumation burials in cemeteries where decapitations were found. The York burials were so unique because of the unprecedented high proportion of decapitated individuals in the cemetery, four times higher than the proportion found in any other Romano-British cemetery. The second highest number of decapitations is 15 out of 94 burials (16%) unearthed from a Roman cemetery in Cassington, Oxfordshire.

Decapitated remains have been found in Roman cemeteries before, but very few. One study tallied 98 decapitations making up 6% of the inhumation burials in cemeteries where decapitations were found. The York burials were so unique because of the unprecedented high proportion of decapitated individuals in the cemetery, four times higher than the proportion found in any other Romano-British cemetery. The second highest number of decapitations is 15 out of 94 burials (16%) unearthed from a Roman cemetery in Cassington, Oxfordshire.

Another unique feature of the Driffield Terrace burials is that they were all men. Decapitated individuals found in all the other Roman burial grounds had the usual demographic spread you’d expect of an attritional cemetery. There were men, women, young, old, adult, child. The York burials were also all under the age of 45 and taller than average. Five of them had other wounds inflicted by a blade besides the cuts to the neck, jaw, clavicle and scapula associated with

Another unique feature of the Driffield Terrace burials is that they were all men. Decapitated individuals found in all the other Roman burial grounds had the usual demographic spread you’d expect of an attritional cemetery. There were men, women, young, old, adult, child. The York burials were also all under the age of 45 and taller than average. Five of them had other wounds inflicted by a blade besides the cuts to the neck, jaw, clavicle and scapula associated with  decapitation. Two were stabbed in the abdomen; one was cut through the thigh muscles to the femur; two were parrying fractures to the forearm and hand, likely incurred trying to deflect a blow to the head. Sixteen individuals had perimortem blunt force trauma to the cranium. Evidence of healed trauma was rife, including cranial, facial, dental and metacarpal fractures that were likely incurred by violence. One skeleton’s pelvis showed signs of what may have been bite marks from a lion or bear.

decapitation. Two were stabbed in the abdomen; one was cut through the thigh muscles to the femur; two were parrying fractures to the forearm and hand, likely incurred trying to deflect a blow to the head. Sixteen individuals had perimortem blunt force trauma to the cranium. Evidence of healed trauma was rife, including cranial, facial, dental and metacarpal fractures that were likely incurred by violence. One skeleton’s pelvis showed signs of what may have been bite marks from a lion or bear.

Osteological evidence indicates they were trained to fight from a young age. Their right arms were consistently longer than their left, which means they’d been using weapons regularly since before they’d finished growing. Most them also showed signs of inadequate nutrition in childhood which they overcame to become healthy, strapping young men.

Osteological evidence indicates they were trained to fight from a young age. Their right arms were consistently longer than their left, which means they’d been using weapons regularly since before they’d finished growing. Most them also showed signs of inadequate nutrition in childhood which they overcame to become healthy, strapping young men.

The single-sex grouping, young age, height and extensive evidence of violence indicated these were fighting men, but just what kind was unclear. The cemetery was southwest of the city walls of Roman Eboracum along the main road to Tadcaster just across the river from the legionary fortress. Legionaries had an age limit and height requirement. Gladiators or criminals sentenced to death were the other possibilities.

The placement of the cemetery atop a promontory on the main road makes it unlikely that they were criminals or outcasts. It’s too sweet a spot to leave it to executed criminals. The date of the burials — from the 2nd to the 4th century A.D. — was an important time for York. Roman emperor Septimius Severus actually lived in Eboracum off and on during the early 3rd century when it was the capital of the Britannia.

To determine the place of original of the individuals, a team from Trinity College Dublin used cutting-edge genomic analysis. DNA was extracted from the dense inner ear bones of seven of the Driffield Terrace burials and subjected to whole genome analysis.

To determine the place of original of the individuals, a team from Trinity College Dublin used cutting-edge genomic analysis. DNA was extracted from the dense inner ear bones of seven of the Driffield Terrace burials and subjected to whole genome analysis.

The nearest modern descendants of the Roman British men sampled live not in Yorkshire, but in Wales. A man from a Christian Anglo-Saxon cemetery in the village of Norton, Teesside, has genes more closely aligned to modern East Anglia and Dutch individuals and highlights the impact of later migrations upon the genetic makeup of the earlier Roman British inhabitants.

However, one of the decapitated Romans had a very different story, of Middle Eastern origin he grew up in the region of modern day Palestine, Jordan or Syria before migrating to this region and meeting his death in York.

This is the first genomic analysis of ancient Britons, but given the precision of the results it’s certainly not the last.

Rui Martiniano who undertook the analysis said: “This is the first refined genomic evidence for far-reaching ancient mobility and also the first snapshot of British genomes in the early centuries AD, indicating continuity with an Iron Age sample before the migrations of the Anglo-Saxon period.”

You can read the full genomic study in this month’s Nature Communications.