The British Library has begun a massive project to digitize all of King George III’s 50,000-piece map collection. George III was an avid collector, not just of things he personally loved but in true Enlightenment style, of things he thought would be of intellectual value to the nation. He added significantly to the royal art collection, dedicated a lifetime to collecting books that he made available to all scholars (not even John Adams was barred) and put together an extensive collection of mathematical and scientific instruments.

Maps and topography were a genuine passion of the king’s and had been since he was a young boy. There’s a well-known portrait of George III when he was Prince of Wales with his younger brother Edward Augustus at their lessons with tutor Francis Ayscough. Next to the future king is a globe, a book with an imprint of the Prince of Wales’ feathers leaning against it. It’s a prescient image. Once he was king, his love of geography became professionally important as well, and there are accounts of his dedication to learning every detail about the topographical details of ports, fortresses and cities.

Maps and topography were a genuine passion of the king’s and had been since he was a young boy. There’s a well-known portrait of George III when he was Prince of Wales with his younger brother Edward Augustus at their lessons with tutor Francis Ayscough. Next to the future king is a globe, a book with an imprint of the Prince of Wales’ feathers leaning against it. It’s a prescient image. Once he was king, his love of geography became professionally important as well, and there are accounts of his dedication to learning every detail about the topographical details of ports, fortresses and cities.

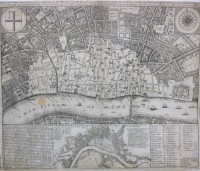

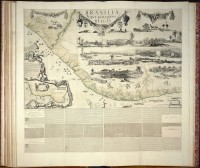

While British monarchs before him had squirreled away maps and atlases in various nooks of royal palaces, it was George III who brought them all together into a single collection that he then added to extensively. He had agents scouring Europe to acquire important pieces and even whole collections. He incorporated all gifts of maps and atlases to the monarch from his subjects into the collection. He even straight-up stole from royal engineers, military and colonial mapmakers who sent drawings, prints and watercolors for his inspection. Late 18th century land surveys done by British military surveyors for the American Board of Trade, for example, never made it to their commissioner. George was so enthralled with the series, which included a map of the Florida coast more than 22 feet long, that he just kept them all, bless his heart, and added them to the ever-expanding collection kept in a room next to his sleeping chamber in Buckingham House, then not yet an official palace.

By the time of King George III’s death in 1820, the Topographical Collection included 60,000 drawings, watercolors, manuscripts, prints, letters, reports and atlases dating from 1500 to the then-present. Half of the material covers Britain and its colonies (or former colonies after the American Revolution) while about 30% covers European countries like Italy and France that were popular Grand Tour destinations. The map collection was gifted to the nation by his son, George IV, along with the late king’s book collection. (He kept all the military maps for national security purposes.)

By the time of King George III’s death in 1820, the Topographical Collection included 60,000 drawings, watercolors, manuscripts, prints, letters, reports and atlases dating from 1500 to the then-present. Half of the material covers Britain and its colonies (or former colonies after the American Revolution) while about 30% covers European countries like Italy and France that were popular Grand Tour destinations. The map collection was gifted to the nation by his son, George IV, along with the late king’s book collection. (He kept all the military maps for national security purposes.)

Originally dispatched to the British Museum, George III’s Topographical Collection was moved to the British Library. Despite its royal pedigree and historical significance, the full collection was never thoroughly catalogued. The British Library moved to remedy that in 2013, raising funds from private donors to catalogue, conserve and digitize George’s beloved maps. It’s a massive job, expensive in time and money, and the library still doesn’t have the funds needed to complete it. They’ve started piecemeal using the donations they have. So far they have conserved, catalogued and digitized all color views, the maps and atlases of South and North America, China, Scotland, southwest England, Spain and 30% of London and southeast England. As of last month, about 25% of the collection has been digitized.

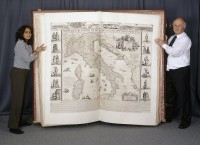

Right now the project is working on the gem of the collection, the gigantic The Klencke Atlas which was the world’s largest atlas until the publication of the Earth Platinum atlas in 2012 which is new so as far as I’m concerned it doesn’t count. At 5’9″ by 6’3″ when open, the atlas is literally man-sized. It wasn’t actually one of George III’s acquisitions. The atlas was given to King Charles II, a known map aficionado, in 1660 by a group of Dutch merchants led by sugar merchant Johannes Klencke as a gift celebrating the king’s restoration to the throne. On its huge pages are 41 walls maps of Europe, Britain, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East. Charles II liked it so much he put it with his most prized objects in his cabinet of curiosities at Whitehall Palace.

Right now the project is working on the gem of the collection, the gigantic The Klencke Atlas which was the world’s largest atlas until the publication of the Earth Platinum atlas in 2012 which is new so as far as I’m concerned it doesn’t count. At 5’9″ by 6’3″ when open, the atlas is literally man-sized. It wasn’t actually one of George III’s acquisitions. The atlas was given to King Charles II, a known map aficionado, in 1660 by a group of Dutch merchants led by sugar merchant Johannes Klencke as a gift celebrating the king’s restoration to the throne. On its huge pages are 41 walls maps of Europe, Britain, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East. Charles II liked it so much he put it with his most prized objects in his cabinet of curiosities at Whitehall Palace.

The Klencke Atlas has long been a favorite with British Library staff — there are photographs of curators being dwarfed by it going back to the 19th century — but photographing the giant pages themselves in any kind of quality was all but impossible until recently. The technology now makes it possible to capture high resolution images of sections of every page and digitally knit them together into a single image. This will give viewers the chance to the see both the big picture, as it were, of each page and to zoom in on the tiny details — names, labels, etc. — that would have been too blurred out to read a decade ago.

The digitization of the Klencke Atlas and 80 other pieces was funded by a donation from rare book seller Daniel Crouch who has a lovely outlook on the matter.

The digitization of the Klencke Atlas and 80 other pieces was funded by a donation from rare book seller Daniel Crouch who has a lovely outlook on the matter.

Crouch admits that it is “an unsexy cause — it’s not like naming a gallery. It is the digitisation of a lot of old stuff.” He stresses that, although “it doesn’t sound important or life-saving, it actually is. It’s the kind of resource that will be used in years to come and will make the holdings of the British Library accessible to all.”

The digitization of the Klencke Atlas is scheduled to be complete by the end of 2016. Meanwhile, there’s the other 75% of the Topographical Collection that still needs love and attention before we can spend entire weekends on a nerd bender of George III’s maps. The British Library needs another £500,000 ($730,000) to finish the job. To donate to the digitization project, go here and select “Unlock London maps” from the dropdown (it should be selected by default) once you’ve chosen an amount and clicked through.