The first Dare Stone was found by a California grocer named Louis E. Hammond who claimed to have discovered it while looking for hickory nuts in a swamp on the east bank of the Chowan River near Edenton, North Carolina, in September of 1937. He couldn’t read the inscription which appeared to be in an unknown foreign language. Two months later he showed the stone to historians at Emory University in Atlanta, among them Dr. Haywood Pearce, Jr., hoping to get the inscription translated. They determined that it was English and made out the names “Ananias Dare & Virginia” on the front of the stone.

The first Dare Stone was found by a California grocer named Louis E. Hammond who claimed to have discovered it while looking for hickory nuts in a swamp on the east bank of the Chowan River near Edenton, North Carolina, in September of 1937. He couldn’t read the inscription which appeared to be in an unknown foreign language. Two months later he showed the stone to historians at Emory University in Atlanta, among them Dr. Haywood Pearce, Jr., hoping to get the inscription translated. They determined that it was English and made out the names “Ananias Dare & Virginia” on the front of the stone.

Those names rang a very loud bell. The daughter of Ananias and Eleanor White Dare, Virginia Dare was the first English child born in North America. She and her parents were part of a group of English settlers sent by Sir Walter Raleigh to settle his land claim in the Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia. Eleanor’s father John White dropped the 118 people off on Roanoke Island in July of 1587 and went back to England for supplies a couple of weeks later. His return was delayed by a little contretemps with the Spanish Armada. When he finally reached the shores of Roanoke again three years had passed and the only sign of his daughter, granddaughter and the rest of the colonists was the word “CROATOAN” carved on a wooden post. Neither White nor anyone else that we know of saw any of the Roanoke colonists again.

Those names rang a very loud bell. The daughter of Ananias and Eleanor White Dare, Virginia Dare was the first English child born in North America. She and her parents were part of a group of English settlers sent by Sir Walter Raleigh to settle his land claim in the Chesapeake Bay area of Virginia. Eleanor’s father John White dropped the 118 people off on Roanoke Island in July of 1587 and went back to England for supplies a couple of weeks later. His return was delayed by a little contretemps with the Spanish Armada. When he finally reached the shores of Roanoke again three years had passed and the only sign of his daughter, granddaughter and the rest of the colonists was the word “CROATOAN” carved on a wooden post. Neither White nor anyone else that we know of saw any of the Roanoke colonists again.

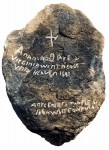

The full inscription appeared to be a note from Eleanor White Dare to her father. The front read: “Ananias Dare &/ Virginia Went Hence/ Unto Heaven 1591/ Anye Englishman Shew/ John White Govr Via.” On the back was carved:

The full inscription appeared to be a note from Eleanor White Dare to her father. The front read: “Ananias Dare &/ Virginia Went Hence/ Unto Heaven 1591/ Anye Englishman Shew/ John White Govr Via.” On the back was carved:

“Father Soone After You/ Goe for England Wee Cam/ Hither. Onlie Misarie & Warre/ Tow Yeere. Above Halfe Deade ere Tow/ Yeere More From Sickenes Beine Foure & Twentie./ Salvage with Message of Shipp Unto Us. Smal/ Space of Time they Affrite of Revenge Rann/ Al Awaye. Wee Bleeve it Nott You. Soone After/ Ye Salvages Faine Spirits Angrie. Suddaine/ Murther Al Save Seaven. Mine Childe. Ananais to Slaine wth Much Misarie./ Burie Al Neere Foure Myles Easte This River/ Uppon Small Hil. Names Writ Al Ther/ On Rocke. Putt This Ther Alsoe. Salvage/ Shew This Unto You & Hither Wee/ Promise You to Give Greate/ Plentie Presents. EWD”

History.com has an excellent zoomable viewer that allows you to vew the stone and its inscription in great detail. Here’s the front. Here’s the back.

Excited at the prospect of having found a remarkably full account of one of the great mysteries of American history, Pearce decided to follow up on the stone. Emory wasn’t interested in pursuing it, so Pearce, who was vice president of Brenau College (today Brenau University) in Gainesville, Georgia, where his father, Haywood Pearce, Sr., was president, recommended the college acquire the stone. It did, for $1,000. Shortly thereafter, Pearce Jr. went with Hammond to the purported find site. Pearce thought it might be a grave marker and hoped to discover the grave of Ananias and Virginia Dare. They found nothing that first time and found nothing the four more times they explored the swamps over the next year and a half, but the locals reported all kinds of stories of having seen other stones, even the mast of a ship, in the swamp.

Excited at the prospect of having found a remarkably full account of one of the great mysteries of American history, Pearce decided to follow up on the stone. Emory wasn’t interested in pursuing it, so Pearce, who was vice president of Brenau College (today Brenau University) in Gainesville, Georgia, where his father, Haywood Pearce, Sr., was president, recommended the college acquire the stone. It did, for $1,000. Shortly thereafter, Pearce Jr. went with Hammond to the purported find site. Pearce thought it might be a grave marker and hoped to discover the grave of Ananias and Virginia Dare. They found nothing that first time and found nothing the four more times they explored the swamps over the next year and a half, but the locals reported all kinds of stories of having seen other stones, even the mast of a ship, in the swamp.

Pearce was tantalized by the possibility that there might be more markers with information on the Lost Colony and recklessly offered a $500 reward for any stones connected to the Roanoke colonists. Not surprisingly, inscribed stones suddenly started popping up like weeds. Brenau University wound up with close to 50 of these stones, most of them “discovered” by a stonecutter from Fulton County, Georgia, named Bill Eberhardt. Three other people who claimed to have found inscribed stones were later found to be connected to Eberhardt.

A 1940 preliminary report by a team of 34 historians commissioned by the Smithsonian Institution and headed by Samuel Eliot Morison of Harvard found no evidence the stones were fake and declared that a “preponderance of evidence points to the authenticity of the stones.” The Dare Stones made big headlines, putting Brenau on the map. Cecil B. DeMille expressed interest in doing a movie about Roanoke based on the stones.

The good press came to an end on April 26th, 1941, when an article by Boyden Sparkes in the Saturday Evening Post exposed the stones as frauds, possibly made in collusion with the Pearces who had received much benefit in prestige and attention. The spelling was too consistent to be Elizabethan, Sparkes’ research concluded, and words like “primeval” and “reconnoiter” in the inscriptions weren’t used in English until a century after the time they were meant to have been carved in stone. Hammond was a shadowy figure that not even the Pinkerton Detective Agency could pin down. The stones were found as far south as the Chattahoochee River just outside Atlanta, an implausible distance for this trail of stone bread crumbs to travel.

Just like that, the Dare Stones fell into ignomy and obscurity. They were kept in the Brenau University basement boiler room and only rarely received attention from scholars and documentarians. They made an appearance in a 1977 episode of the In Search of… series hosted by Leonard Nimoy dedicated to the Lost Colony. (Watch the full episode here.) A book published in 1991, A Witness for Eleanor Dare, by Robert W. White, rebutted Sparkes’ article and weighed in on the side of authenticity. In 2013, the History Channel documentary Mystery of Roanoke touched on the stones. Last October, the History Channel dedicated a new special to the Dare Stones. Roanoke: Search for the Lost Colony found new linguistic evidence suggesting that the first stone might be authentic.

Just like that, the Dare Stones fell into ignomy and obscurity. They were kept in the Brenau University basement boiler room and only rarely received attention from scholars and documentarians. They made an appearance in a 1977 episode of the In Search of… series hosted by Leonard Nimoy dedicated to the Lost Colony. (Watch the full episode here.) A book published in 1991, A Witness for Eleanor Dare, by Robert W. White, rebutted Sparkes’ article and weighed in on the side of authenticity. In 2013, the History Channel documentary Mystery of Roanoke touched on the stones. Last October, the History Channel dedicated a new special to the Dare Stones. Roanoke: Search for the Lost Colony found new linguistic evidence suggesting that the first stone might be authentic.

Now Brenau University is taking a fresh look at the first Dare Stone, the only one that has even a chance of being real.

[Brenau President Ed] Schrader has begun to assemble a team of experts in various disciplines—archaeology, geology, history and the study of Elizabethan writing—to re-examine the quartz stone. Sometime in this year or next, he wants to launch an expedition to the Chowan River near Edenton, N.C., where the first rock is believed to have been found, to search for more evidence.

“If it is real, it is the most important pre-colonial artifact by Europeans in the Americas,” the 64-year-old says, softly placing is fingers on the stone. “The speculation’s gone on long enough.”