Speaking of Queen Elizabeth I, Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) curators think an altar cloth from St Faith’s Church in Bacton, Herefordshire, may be the only known surviving piece of one of the monarch’s famously elaborate gowns. There is no conclusive proof that the cross-shaped piece of fabric once belonged to the queen herself, but there’s very solid circumstantial evidence.

Speaking of Queen Elizabeth I, Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) curators think an altar cloth from St Faith’s Church in Bacton, Herefordshire, may be the only known surviving piece of one of the monarch’s famously elaborate gowns. There is no conclusive proof that the cross-shaped piece of fabric once belonged to the queen herself, but there’s very solid circumstantial evidence.

The altar cloth has belonged to the small rural church for centuries. The richly embroidered cloth, long rumored to have a connection to the Virgin Queen, stopped being used as altar cloth and was placed in a glass display case in 1909. The church received it from Blanche Perry, daughter of a Welsh nobleman who was born in Bacton and became one of the queen’s most loyal and longest serving ladies. Brought to court by her aunt Lady Troy who Henry VIII appointed Lady Mistress to his children Prince Edward and Princess Elizabeth, Blanche was Elizabeth’s attendant for 57 years, ultimately rising to the exalted rank of Chief Gentlewoman of Queen Elizabeth’s most honourable Privy Chamber and Keeper of Her Majesty’s jewels, a role she held from 1565 until her death in 1590.

An epitaph she wrote for her funerary monument at St Faith’s describes her lifelong dedication to the Princess and later Queen Elizabeth, “whose cradle saw I rocked, her servant then as when she her crown achieved and remained til death my door had knocked…. A maid in court and never no man’s wife, sworn of Queen Elizabeth’s head chamber always with the Maiden Queen a maid did end my life.” She commissioned the monument at the time of her planned retirement (1576-1577), but she never did retire. She was Chief Gentlewoman until the end, after which the Queen had her buried with much pomp in St. Margaret’s, Westminster. Only her heart made it back to St Faith’s, her heart and a beautiful piece of fabric.

An epitaph she wrote for her funerary monument at St Faith’s describes her lifelong dedication to the Princess and later Queen Elizabeth, “whose cradle saw I rocked, her servant then as when she her crown achieved and remained til death my door had knocked…. A maid in court and never no man’s wife, sworn of Queen Elizabeth’s head chamber always with the Maiden Queen a maid did end my life.” She commissioned the monument at the time of her planned retirement (1576-1577), but she never did retire. She was Chief Gentlewoman until the end, after which the Queen had her buried with much pomp in St. Margaret’s, Westminster. Only her heart made it back to St Faith’s, her heart and a beautiful piece of fabric.

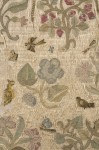

Experts from the Historic Royal Palaces asked to examine the textile last year. They identified it as an Elizabethan skirt panel from the late 16th century, and not just any skirt panel, but one of royal quality. It is cream silk woven through with silver thread with embroidery in colored silks, gold thread and silver thread. It was embroidered with florals — columbines, daffodils, roses, honeysuckle, oak leaves, acorns, mistletoe — and animals — birds, dragonflies, butterflies, caterpillars, frogs, fish, dogs, stags, squirrels. There are also miniature boats being rowed by tiny humans. This was professional embroidery of the highest standard.

Experts from the Historic Royal Palaces asked to examine the textile last year. They identified it as an Elizabethan skirt panel from the late 16th century, and not just any skirt panel, but one of royal quality. It is cream silk woven through with silver thread with embroidery in colored silks, gold thread and silver thread. It was embroidered with florals — columbines, daffodils, roses, honeysuckle, oak leaves, acorns, mistletoe — and animals — birds, dragonflies, butterflies, caterpillars, frogs, fish, dogs, stags, squirrels. There are also miniature boats being rowed by tiny humans. This was professional embroidery of the highest standard.

The sumptuary laws explicitly reserved such rich garments for members of the immediate royal family. A single gown could cost the equivalent of labourer’s yearly income. Curators believe it was a gift from the Queen to Blanche Parry, a rare, valued gift that was a token of the Queen’s high esteem, love and friendship. Queen Elizabeth didn’t give away her dresses very often, and no garments from her royal wardrobe have survived, only accessories. This section is the only piece of fabric known that is likely to have come from a gown of Elizabeth’s. It survived because it was treated with reverence, very quickly converted into an altar piece and treated with utmost care for the next four centuries.

The HRP curators have removed it from its frame and frozen it to kill any critters that might have been gnawing on its delicate fibers. Conservators will now analyze it and recommend a course of action that will preserve it in the long term. After it is conserved in the laboratories of Hampton Court, HRP hopes it will go on public display. St Faith’s is still the undisputed owner, however, so they’ll have to determine where it will be exhibited in the long-term. One possibility is that a replica will be made for the church, while the original is kept in the security and ideal conservation conditions of the Historic Royal Palaces.

The HRP curators have removed it from its frame and frozen it to kill any critters that might have been gnawing on its delicate fibers. Conservators will now analyze it and recommend a course of action that will preserve it in the long term. After it is conserved in the laboratories of Hampton Court, HRP hopes it will go on public display. St Faith’s is still the undisputed owner, however, so they’ll have to determine where it will be exhibited in the long-term. One possibility is that a replica will be made for the church, while the original is kept in the security and ideal conservation conditions of the Historic Royal Palaces.