A team of British and Puerto Rican archaeologists have discovered a collection of early colonial inscriptions alongside earlier indigenous iconography on the walls of a cave on the Caribbean island of Mona. It’s a unique document of the interaction between indigenous and European culture and at the time of their earliest interactions.

A team of British and Puerto Rican archaeologists have discovered a collection of early colonial inscriptions alongside earlier indigenous iconography on the walls of a cave on the Caribbean island of Mona. It’s a unique document of the interaction between indigenous and European culture and at the time of their earliest interactions.

Columbus first encountered Mona, a small island between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, on his second voyage in 1494. Its location within a day’s canoe trip of the larger islands ensured the indios of Mona were well-connected to interregional trade networks, and when the Spanish arrived, the island found itself on one of the main Atlantic routes to and from the Indies. The indigenous population sold supplies to the ships — cassava bread, water — and produced consumer goods like cotton shirts and hammocks to the first settlers. Thus the people of Mona were involved with Europeans from the beginning, modifying their own behaviors and traditions in response to first contact and colonization, and in turn having an impact on the Spanish as they and their children began to forge a new American identity.

Columbus first encountered Mona, a small island between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, on his second voyage in 1494. Its location within a day’s canoe trip of the larger islands ensured the indios of Mona were well-connected to interregional trade networks, and when the Spanish arrived, the island found itself on one of the main Atlantic routes to and from the Indies. The indigenous population sold supplies to the ships — cassava bread, water — and produced consumer goods like cotton shirts and hammocks to the first settlers. Thus the people of Mona were involved with Europeans from the beginning, modifying their own behaviors and traditions in response to first contact and colonization, and in turn having an impact on the Spanish as they and their children began to forge a new American identity.

The archaeology of Mona reflects this cultural blending process. European glass beads, storage jars, ceramics, coins and the remains of livestock from 1493 through 1590 have been found on the island mixed with indigenous artifacts — ceramics, tools — and equipment for the processing of food. The vast cave networks dotting the Isle of Mona display the same mixing of cultures in the form of art and inscriptions on the walls and ceilings.

The archaeology of Mona reflects this cultural blending process. European glass beads, storage jars, ceramics, coins and the remains of livestock from 1493 through 1590 have been found on the island mixed with indigenous artifacts — ceramics, tools — and equipment for the processing of food. The vast cave networks dotting the Isle of Mona display the same mixing of cultures in the form of art and inscriptions on the walls and ceilings.

Mona is practically more cave than anything else. Sheer limestone cliffs line the shores, peppered with more than 200 cave systems. Because the surface of the island is thick with plant life, the cool, rocky caves became a sort of subway system where the locals could travel to other points without having to hack their way through dense vegetation. The caves were also the island’s sole source of fresh water. Clear indications of indigenous usage has been found in 30 of the 70 cave systems on the island that have been studied by archaeologists since 2013.

Mona is practically more cave than anything else. Sheer limestone cliffs line the shores, peppered with more than 200 cave systems. Because the surface of the island is thick with plant life, the cool, rocky caves became a sort of subway system where the locals could travel to other points without having to hack their way through dense vegetation. The caves were also the island’s sole source of fresh water. Clear indications of indigenous usage has been found in 30 of the 70 cave systems on the island that have been studied by archaeologists since 2013.

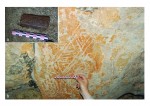

The caves of Mona have the greatest variety of surviving indigenous iconography in the Caribbean. Symbols including geometric shapes, swirling meanders, anthropomorphic and anthrozoomorphic figures have been found on the walls and ceilings of cave chambers. The inscribed caves are hard to get to, their entrances small, person-sized holes high up on the cliff face, and the indigenous artwork only appears in the deep dark inside the caves, far from the light of the entrance. These were likely deliberate choices, as caves and the iconography held religious significance. The Europeans followed, perhaps literally, in indigenous footsteps to add their own religious spin to the sacred spaces of Mona.

The caves of Mona have the greatest variety of surviving indigenous iconography in the Caribbean. Symbols including geometric shapes, swirling meanders, anthropomorphic and anthrozoomorphic figures have been found on the walls and ceilings of cave chambers. The inscribed caves are hard to get to, their entrances small, person-sized holes high up on the cliff face, and the indigenous artwork only appears in the deep dark inside the caves, far from the light of the entrance. These were likely deliberate choices, as caves and the iconography held religious significance. The Europeans followed, perhaps literally, in indigenous footsteps to add their own religious spin to the sacred spaces of Mona.

In Cave 18, archaeologists found 250 indigenous works on the walls and ceilings 10 chambers and tunnels. The soft, swirling motifs were made by “finger-fluting,” ie, dragging one or more fingers through the mineral and organic deposits on the surfaces, and have been radiocarbon dated to the 14th and 15th century. More than 30 inscriptions in Spanish and Latin followed, applied to the same areas. They include proper names, dates and Christian symbols like crosses and the IHS Christogram.

In Cave 18, archaeologists found 250 indigenous works on the walls and ceilings 10 chambers and tunnels. The soft, swirling motifs were made by “finger-fluting,” ie, dragging one or more fingers through the mineral and organic deposits on the surfaces, and have been radiocarbon dated to the 14th and 15th century. More than 30 inscriptions in Spanish and Latin followed, applied to the same areas. They include proper names, dates and Christian symbols like crosses and the IHS Christogram.

Unlike the locals who climbed and crouched to apply their artwork to a variety of locations, the Europeans added their stuff where they stood, at about 1.8 meters — average height for Europeans at that time — above the floor. Also unlike the locals, they carved their inscriptions with edged tools into the limestone.

Three inscribed phrases are present in chambers H and K: ‘Plura fecit deus’, ‘dios te perdone’ and ‘verbum caro factum est (bernardo)’. Palaeographic analysis of letter forms, the use of abbreviation and writing conventions place these in the sixteenth century…. ‘Plura fecit deus’, or ‘God made many things’, is the first inscription encountered after entering chamber H. There is no obvious contemporary textual source; the commentary appears to be a spontaneous response to whatever the visitor experienced in the cave. There is a strong spatial inference that ‘things’ is a reference to the extensive indigenous iconography present. The phrase may express the theological crisis of the New World discovery, throwing the personal human experience and reaction into sharp relief. […]

Particularly striking are two depictions of Calvary. The first consists of three crosses, the central one with the Latin inscription ‘Iesus’ (Jesus) set at a height of over 3m in chamber G…. Stylistically, all three are barred cross-on-base motifs, in use in the sixteenth century; similar examples are found from contemporary contexts in Europe and South America…. A second Calvary panel is made up of two crosses, one of which is a barred cross-on-base, the other a simple two-stroke Latin cross. These flank a pre-existing indigenous anthropomorphic figure. This triptych has clear compositional parallels with representations of Calvary in which the central figure is strikingly cast as an indigenous Jesus.

There are 17 more crosses in the cave, from simple downstroke-and-crosstroke Latin crosses to more complex Potent and Calvary crosses. Some are finger-drawn, probably by converted indios. Many of them were made near and above pre-existing indigenous iconography.

There are 17 more crosses in the cave, from simple downstroke-and-crosstroke Latin crosses to more complex Potent and Calvary crosses. Some are finger-drawn, probably by converted indios. Many of them were made near and above pre-existing indigenous iconography.

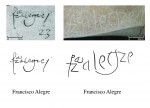

We know it wasn’t indigenous converts doing the carving because several of the Spanish artists did us the courtesy of leaving their Kilroy Wuz Here. From the mid-16th century, Myguel Rypoll,  Alonso Pérez Roldan el Mozo and Alonso de Contreras signed the wall. The above-mentioned Bernardo signed off on his “verbum caro factum est” line, and one Capitán Francisco Alegre, a royal official in Puerto Rico in the mid-16th century, signed his name. It’s actually quite impressive considering he was carving it in the wall how similar it is to his actual signature on a page.

Alonso Pérez Roldan el Mozo and Alonso de Contreras signed the wall. The above-mentioned Bernardo signed off on his “verbum caro factum est” line, and one Capitán Francisco Alegre, a royal official in Puerto Rico in the mid-16th century, signed his name. It’s actually quite impressive considering he was carving it in the wall how similar it is to his actual signature on a page.

[Dr. Alice Samson from the University of Leicester School of Archaeology and Ancient History] said the marks were made by some of the earliest colonisers to arrive in the Americas. These colonisers would have been taken to the caves, places considered particularly sacred, and were responding with respect to what they saw, engaging in a religious dialogue.

“We have this idea of when the first Europeans came to the New World of them imposing a very rigid Christianity. We know a lot about the inquisition in Mexico and Peru and the burning of libraries and the persecution of indigenous religions.

“What we are seeing in this Caribbean cave is something different. This is not zealous missionaries coming with their burning crosses, they are people engaging with a new spiritual realm and we get individual responses in the cave and it is not automatically erasure, it is engagement.”

You can read the full paper published in the journal Antiquity free of charge here.