The moated brick manor house of Oxburgh Hall has been through a myriad cycles of growth, decline, expansion, dereliction and reconstruction since it was first built in 1482 by Sir Edmund Bedingfeld. It came within a hair’s breadth of demolition in 1952 before it was saved at the very last minute by Lady Sybil Bedingfeld who gave it the National Trust. It is currently undergoing a £6million program of repairs to the roof, structural timbers and tiles, 14 dormer windows and its 27 brick chimneys. It is a massive feat of engineering (wrapping a building surrounded by a moat that cannot be drained in full scaffolding is … tricky) and conservation.

The moated brick manor house of Oxburgh Hall has been through a myriad cycles of growth, decline, expansion, dereliction and reconstruction since it was first built in 1482 by Sir Edmund Bedingfeld. It came within a hair’s breadth of demolition in 1952 before it was saved at the very last minute by Lady Sybil Bedingfeld who gave it the National Trust. It is currently undergoing a £6million program of repairs to the roof, structural timbers and tiles, 14 dormer windows and its 27 brick chimneys. It is a massive feat of engineering (wrapping a building surrounded by a moat that cannot be drained in full scaffolding is … tricky) and conservation.

The work on the roof is so extensive that temporary roofing was rigged to allow all of the 17,000+ tiles and coverings to be removed for structural work on the timbers. The floorboards were painstakingly lifted, numbered and removed, exposing the underfloor for the first time in centuries. The floorboards date to a Victorian-era renovation, but builders at the time simply laid them over the 16th and 17th century ceilings, leaving the underfloors entirely undisturbed. Archaeologists expected to find some old discarded fragments under the floors — newspapers, candy wrappers, buttons, pins — and their expectations were quickly met when they discovered a box of Terry’s Gold Leaf chocolates, complete with all the packaging and wrappers, missing only the chocs themselves.

The work on the roof is so extensive that temporary roofing was rigged to allow all of the 17,000+ tiles and coverings to be removed for structural work on the timbers. The floorboards were painstakingly lifted, numbered and removed, exposing the underfloor for the first time in centuries. The floorboards date to a Victorian-era renovation, but builders at the time simply laid them over the 16th and 17th century ceilings, leaving the underfloors entirely undisturbed. Archaeologists expected to find some old discarded fragments under the floors — newspapers, candy wrappers, buttons, pins — and their expectations were quickly met when they discovered a box of Terry’s Gold Leaf chocolates, complete with all the packaging and wrappers, missing only the chocs themselves.

A few weeks later they found some old rats’ nests and it turns out the rodents at Oxburgh Hall had excellent taste in bedding. There were fragments of 16th century sheet music and of a 16th century English edition of the King’s Psalms. Next to the nests was a large fragment from a 15th century illuminated Bible, only slightly gnawed. It contains a passage from Psalm 39 from the Vulgate highlighted with blue and gold letters.

A few weeks later they found some old rats’ nests and it turns out the rodents at Oxburgh Hall had excellent taste in bedding. There were fragments of 16th century sheet music and of a 16th century English edition of the King’s Psalms. Next to the nests was a large fragment from a 15th century illuminated Bible, only slightly gnawed. It contains a passage from Psalm 39 from the Vulgate highlighted with blue and gold letters.

Upon closer examination, two of the nests were found to contain more than 200 fragments of luxury textiles including silk, satin, linen, velvet and leather. There are pieces with fine embroidery and ribbons. They date to the late 16th, early 17th century and were probably snippets of larger sections. The rats recognized their high-end qualities and made off with as many remnants as they could get their tiny little hands on.

Upon closer examination, two of the nests were found to contain more than 200 fragments of luxury textiles including silk, satin, linen, velvet and leather. There are pieces with fine embroidery and ribbons. They date to the late 16th, early 17th century and were probably snippets of larger sections. The rats recognized their high-end qualities and made off with as many remnants as they could get their tiny little hands on.

One of the largest pieces is browny-gold slashed silk, with each of the slashes revealing gold thread. Slashing was very popular for men’s clothing during the 16th century and was used for doublets, jackets and sleeves. It was placed over a textile of a contrasting colour which would be revealed through the slashes. We have the rats to thank for the remarkable condition of these textiles; begin kept below the floorboards for hundreds of years has prevented them from decaying and has allowed us to find out so much more about life at Oxburgh Hall.

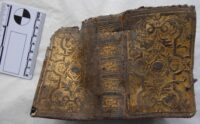

That was in May. Two weeks ago, builders hit a motherlode, not in the rats’ nests but it was in a nearby void in the attic. It is a full leatherbound copy of the King’s Psalms published in 1568 and is in exceptional condition, even if was the source for the fragments found in the rats’ nests. There is only one other copy of this book known to exist and it’s in the British Library.

That was in May. Two weeks ago, builders hit a motherlode, not in the rats’ nests but it was in a nearby void in the attic. It is a full leatherbound copy of the King’s Psalms published in 1568 and is in exceptional condition, even if was the source for the fragments found in the rats’ nests. There is only one other copy of this book known to exist and it’s in the British Library.

The Kynges Psalmes was originally written by John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, in the 1st half of the 16th century and first published in England c.1544. Fisher was executed by Henry VIII for refusing to accept him as the supreme head of the Church of England and is honoured as a martyr and a saint by the Catholic church. Interestingly, this edition was translated into English from Fisher’s Latin by none other than Katherine Parr, who tweaked the emphasis of some of the text (perhaps in collaboration with her husband) in order to emphasise Henry VIII’s religious authority, obedience to God, and military prowess. The English version of The King’s Psalms, which we have at Oxburgh, was therefore highly regarded by Protestants.

This is of particular significance because the Bedingfelds were Catholic, and staunchly so. They were persecuted, fined and harassed for their recusancy. Oxburgh Hall is famous for its priests’ hole, a trapdoor in the floor that is the most popular stop for visitors to the estate.

Russell Clement, general manager,said: “We had hoped to learn more of the history of the house during the reroofing work… but these finds are far beyond anything we expected to see. These objects contain so many clues which confirm the history of the house as the retreat of a devout Catholic family, who retained their faith across the centuries.

“This is a building which is giving up its secrets slowly. We don’t know what else we might come across or what might remain hidden for future generations to reveal.”