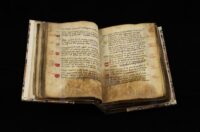

The University of Cambridge has embarked on a two-year project to catalogue, digitize and conserve 180 medieval medical manuscripts in the Cambridge Libraries collection. About 8,000 medical recipes spread in manuscripts at the University Library, the Fitzwilliam Museum and in a dozen individual Cambridge colleges will be published for the first time in the Cambridge Digital Library. High-resolution photographs of the recipes will be accompanied by transcriptions of the text and detailed descriptions of the historical context of the recipes and manuscripts.

The University of Cambridge has embarked on a two-year project to catalogue, digitize and conserve 180 medieval medical manuscripts in the Cambridge Libraries collection. About 8,000 medical recipes spread in manuscripts at the University Library, the Fitzwilliam Museum and in a dozen individual Cambridge colleges will be published for the first time in the Cambridge Digital Library. High-resolution photographs of the recipes will be accompanied by transcriptions of the text and detailed descriptions of the historical context of the recipes and manuscripts.

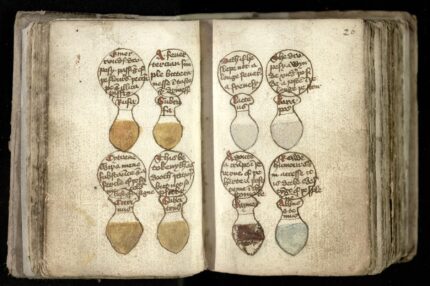

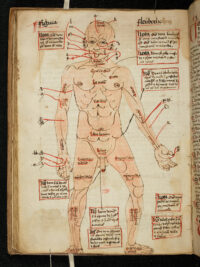

The books vary widely. There are alchemical treatises, devotional books, legal books and of course medical texts, including personal compilations of  home remedies. They are written in Latin, French and Middle English. Most of them to the 14th or 15th centuries with some outliers. The oldest manuscript is 1000 years old. Some are richly illuminated, containing elaborate diagrams of the human body and a prodigious diversity of urine color/smell/taste flowcharts.

home remedies. They are written in Latin, French and Middle English. Most of them to the 14th or 15th centuries with some outliers. The oldest manuscript is 1000 years old. Some are richly illuminated, containing elaborate diagrams of the human body and a prodigious diversity of urine color/smell/taste flowcharts.

The recipes themselves consist of lists of ingredients and instructions for preparation. A great many of them are common plants like herbs and flowers, but when animal ingredients are involved, things get uncomfortably close to that Neo-Babylonian ghost-raising ritual Irving Finkel wanted to try for Halloween a few years ago.

One treatment for gout involves stuffing a puppy with snails and sage and roasting him over a fire: the rendered fat was then used to make a salve. Another proposes salting an owl and baking it until it can be ground into a powder, mixing it with boar’s grease to make a salve, and likewise rubbing it onto the sufferer’s body.

To treat cataracts – described as a ‘web in the eye’ – one recipe recommends taking the gall bladder of a hare and some honey, mixing them together and then applying it to the eye with a feather over the course of three nights.

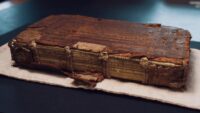

The medical recipe texts of Cambridge form one of the largest medieval medical writing collections in the UK and well-used by scholars, but only a small percentage of interested have had the opportunity to explore the books in person. Many are too fragile to be freely accessed at all and need emergency conservation before they can even be digitized.

The medical recipe texts of Cambridge form one of the largest medieval medical writing collections in the UK and well-used by scholars, but only a small percentage of interested have had the opportunity to explore the books in person. Many are too fragile to be freely accessed at all and need emergency conservation before they can even be digitized.

The project team’s transcriptions will open the manuscripts’ contents to health researchers and historians of medicine, enabling keyword searching, surveys of treatments for specific ailments, or quantitative analyses of particular ingredients or preparatory techniques.

Cover-to-cover digitisation will enable researchers to see the recipes in their original setting: where they were written on the page and how they were presented, and whether they were added by different hands or at different times. Conservation will also guarantee continued physical access to the material for future generations of researchers.

“All of the digital images made by the Library’s Digital Content Unit, together with the detailed descriptions and transcriptions produced by the project cataloguers, will be published on the Cambridge Digital Library – making them available to anyone, anywhere in the world with an internet connection,” said Dr Freeman.