There’s a new contender for oldest message in a bottle. This one was found by retired postal worker Marianne Winkler when it washed up on the shore of the German island of Amrum on the North Sea coast. She was there on vacation, walking on the beach, when she came across the clear bottle on April 17th.

There’s a new contender for oldest message in a bottle. This one was found by retired postal worker Marianne Winkler when it washed up on the shore of the German island of Amrum on the North Sea coast. She was there on vacation, walking on the beach, when she came across the clear bottle on April 17th.

A card inside invited the finder in big, bold red letters to “BREAK THE BOTTLE” but Marianne and her husband Holst first tried to open it without breaking the glass. When that proved impossible, they followed instructions. The message in the bottle was a postage-paid postcard that asked in English, German and

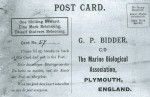

A card inside invited the finder in big, bold red letters to “BREAK THE BOTTLE” but Marianne and her husband Holst first tried to open it without breaking the glass. When that proved impossible, they followed instructions. The message in the bottle was a postage-paid postcard that asked in English, German and  Dutch for finders to answer questions about where they’d found the bottle and when. Everyone who sent their postcard to the Marine Biological Association (MBA) in Plymouth would earn one shiny shilling in reward. The Winklers photocopied the postcard, filling in the information as requested on the copy, then mailed the card and copy to the MBA.

Dutch for finders to answer questions about where they’d found the bottle and when. Everyone who sent their postcard to the Marine Biological Association (MBA) in Plymouth would earn one shiny shilling in reward. The Winklers photocopied the postcard, filling in the information as requested on the copy, then mailed the card and copy to the MBA.

MBA researchers were shocked to receive the Winklers’ missive. There was no date on the card, but they recognized it as one of 1020 bottles released from December 1904 through August 1906 by MBA council member and future president George Parker Bidder. Bidder was studying bottom water currents (currents just above the seabed) and sent out what he called “bottom bottles” to trace the movements of the currents and fish.

MBA researchers were shocked to receive the Winklers’ missive. There was no date on the card, but they recognized it as one of 1020 bottles released from December 1904 through August 1906 by MBA council member and future president George Parker Bidder. Bidder was studying bottom water currents (currents just above the seabed) and sent out what he called “bottom bottles” to trace the movements of the currents and fish.

Bidder’s experiment revealed a number of interesting results, one being that it confirmed the view of naturalists who supposed that bottom feeders tend to move against the current. He concluded that the main drift in all his series of bottle releases seemed to be in the opposite direction to the migration of plaice at the same time of year. Moreover, Bidder expressed the opinion that the percentage of bottles recovered by the trawls did not differ from the percentage of plaice in the same area caught by the trawl at the same time. This meant that Bidder could use the bottles as an instrument for assessing the intensity of trawling because they cannot migrate.

What was probably his most significant finding from his experiments was that many of his bottom-trailers got cast on the English shore, whereas surface bottles would, for the most part go across the North Sea. He deduced, regarding the bottom flow, “that the isochrones of the stream-front were shaped on the shoreline; and such a formation of the bottom current suggested the creeping-in of heavy water.”

Most of the bottles were retrieved by trawlers in the year immediately after their release and researchers assumed the rest were long gone, destroyed or in the open ocean. It’s been years since any cropped up, so many years that nobody even knows when the last one was found. This bottle has traveled more than 600 nautical miles over 108 years, making it the oldest known message in a bottle.

Most of the bottles were retrieved by trawlers in the year immediately after their release and researchers assumed the rest were long gone, destroyed or in the open ocean. It’s been years since any cropped up, so many years that nobody even knows when the last one was found. This bottle has traveled more than 600 nautical miles over 108 years, making it the oldest known message in a bottle.

The official record-holder for oldest message in a bottle, found 99 years and 43 days after its 1914 release, was also released as part of a study of undercurrents. It was one 1,890 bottles released by the Glasgow School of Navigation to map the currents around Scotland and it seems to have understood its brief well because it was retrieved from the waters west of the Shetland Islands.

It’s not really the oldest message in a bottle, though. The message from a German hiker found by Baltic fishermen last year was released in 1913 and floated for almost 101 years, and one found in British Columbia in 2013 was released in September of 1906 by a passenger on a steamer traveling from San Francisco to Bellingham, Washington. The Baltic message hasn’t been confirmed as a record yet, and the finder of the bottle in Canada didn’t want to open it for fear of damaging it, so even though he said he was planning on writing the Guinness World Records committee, unless he was willing to open the bottle its age couldn’t be confirmed.

The Winkler’s bottle is older than both of them. The latest it could have been released was a month before the one found in British Columbia was released, and it stayed in the water two years longer. I know the records committee isn’t in the business of judging quality, but perhaps there should be some distinction made between bottles released in oceanographic studies and ones released by individuals. The odds of one of thousands of bottles surviving a century are obviously significantly higher than the odds of a single bottle surviving, and when you think “message in a bottle,” mass-mailings aren’t really what come to mind. The fascination of the message in a bottle relies on the romantic image of one person casting his or her thoughts into the world in the hope that someone somewhere might find it.

The MBA has submitted its candidate for the oldest message in a bottle to the Guinness Book of World Records and are waiting to hear back. Meanwhile, they made good on Bidder’s promise. They found a period English shilling on eBay and sent it to the Winklers.

The MBA has submitted its candidate for the oldest message in a bottle to the Guinness Book of World Records and are waiting to hear back. Meanwhile, they made good on Bidder’s promise. They found a period English shilling on eBay and sent it to the Winklers.