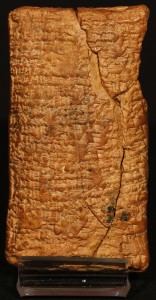

A marble slab inscribed with Roman-era water laws has been unearthed in the ancient city of Laodicea in western Turkey. The highly detailed law was written by the Laodicea Assembly in 114 A.D. and approved by Aulus Vicirius Martialis, proconsul of the Roman Asia province, in the provincial capital at Ephesus. It was carved on a slab and erected in the city to put fear in the heart of all water scofflaws.

A marble slab inscribed with Roman-era water laws has been unearthed in the ancient city of Laodicea in western Turkey. The highly detailed law was written by the Laodicea Assembly in 114 A.D. and approved by Aulus Vicirius Martialis, proconsul of the Roman Asia province, in the provincial capital at Ephesus. It was carved on a slab and erected in the city to put fear in the heart of all water scofflaws.

The Roman affinity for practical engineering ensured cities had access to public water. Aqueducts carried enormous quantities of water from nearby sources to the urbs where it was split up into lead pipes and reservoirs supplying the fountains, baths and drinking water throughout the city. Keeping people from illegally tapping into the pipes to supply their own homes was a constant struggle. If too many people helped themselves, not only would the water flow be disrupted for their neighbors, but the sewer system tied into the water system suffered as well since it required regular flushing. Backed up sewers and low water supply make for uncomfortable and dangerously unsanitary conditions in any city.

Water management was thus an essential aspect of city administration and violators of the common water good were subject to heavy penalties. In Laodicea, anyone caught polluting the water, damaging the pipes and channels, opening sealed pipes or stealing the city water for private use would have to pay fines as high as 12,500 denarii. A legionary was paid 300 denarii a year in the early second century A.D., so fines in the thousands would be complete disasters for regular people. Many of the most egregious public water thieves were quite wealthy since they had homes into which city water could be easily and discretely diverted, so it was important that the fines be large if they were to act as any kind of deterrent.

[Excavations head Professor Celal Şimşek of Pamukkale University] said the 1,900-year-old rules to prevent water pollution had a very special place, adding, “The fine for damaging the water channel or polluting the water is 5,000 denarius, nearly 50,000 Turkish Liras. The fine is the same for those who break the seal and attempt illegal use. Also, there are penalties for senior staff that overlook the illegal use of water. They pay 12,500 denarius. Those who denounce the polluters are given one-eighth of the penalty as a reward, according to the rules.”

A translation from the Greek of one section of the inscription:

“Those who divide the water for his personal use, should pay 5,000 denarius to the imperial treasury; it is forbidden to use the city water for free or grant it to private individuals; those who buy the water cannot violate the Vespasian Edict; those who damage water pipes should pay 5,000 denarius; protective roofs should be established for the water depots and water pipes in the city; the governor’s office [will] appoint two citizens as curators every year to ensure the safety of the water resource; nobody who has farms close to the water channels can use this water for agriculture.”

Founded in the 3rd century B.C., Laodicea was part of the Kingdom of Pergamon when its last king Attalus III bequeathed it to Rome in 133 B.C. Laodicea was hard hit during the two decades of war between Rome and Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, and it was only after the end of the last Mithraditic War (75-63 B.C.) that the sleepy town grew into prosperous city under Roman rule. Strabo, who was himself a native of Amasya, Pontus, (now Turkey) and whose family held important positions under Mithridates VI, describes the rise Laodicea in Book XII, Chapter 8.16 of his Geography:

Founded in the 3rd century B.C., Laodicea was part of the Kingdom of Pergamon when its last king Attalus III bequeathed it to Rome in 133 B.C. Laodicea was hard hit during the two decades of war between Rome and Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, and it was only after the end of the last Mithraditic War (75-63 B.C.) that the sleepy town grew into prosperous city under Roman rule. Strabo, who was himself a native of Amasya, Pontus, (now Turkey) and whose family held important positions under Mithridates VI, describes the rise Laodicea in Book XII, Chapter 8.16 of his Geography:

Laodiceia, though formerly small, grew large in our time and in that of our fathers, even though it had been damaged by siege in the time of Mithridates Eupator. However, it was the fertility of its territory and the prosperity of certain of its citizens that made it great: at first Hieron, who left to the people an inheritance of more than two thousand talents and adorned the city with many dedicated offerings, and later Zeno the rhetorician and his son Polemon, the latter of whom, because of his bravery and honesty, was thought worthy even of a kingdom, at first by Antony and later by Augustus. The country round Laodiceia produces sheep that are excellent, not only for the softness of their wool, in which they surpass even the Milesian wool, but also for its raven-black colour, so that the Laodiceians derive splendid revenue from it[.]