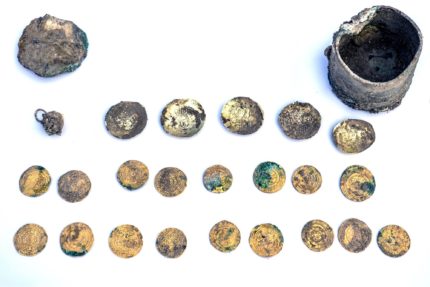

Archaeologists have discovered a bronze pot containing 24 rare 11th century coins from the Byzantine Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate. One gold pendant earring was included with the coins in the pot before it was buried between two stones on the edge of a well in an Islamic-era home.

Archaeologists have discovered a bronze pot containing 24 rare 11th century coins from the Byzantine Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate. One gold pendant earring was included with the coins in the pot before it was buried between two stones on the edge of a well in an Islamic-era home.

The coins are very high value. There are 18 Fatimid dinars composed of 24K gold, five coins of Byzantine Emperor Michael VII Doukas (1071 – 1078 A.D.)  and one of Romanos III (1028 – 1034 A.D.), both of 22K gold. This is an unusual mixture of investment-sized denominations. It strongly suggests whoever buried this hoard was a merchant or trader of some sort. Large, highly recognizable and highly valued denominations were used to make deals on large quantities, not as walk-around cash. They were not in circulation in Cesarea. They were barely in circulation anywhere. The Byzantine coins almost never left the boundaries of the Empire period. Only a few of them have been found in Israel before.

and one of Romanos III (1028 – 1034 A.D.), both of 22K gold. This is an unusual mixture of investment-sized denominations. It strongly suggests whoever buried this hoard was a merchant or trader of some sort. Large, highly recognizable and highly valued denominations were used to make deals on large quantities, not as walk-around cash. They were not in circulation in Cesarea. They were barely in circulation anywhere. The Byzantine coins almost never left the boundaries of the Empire period. Only a few of them have been found in Israel before.

Even the bronze pot the treasure was buried in was expensive and special. Usually hoards were wrapped and buried in wood or pottery. The bronze container would have had significant value just on its own. There’s evidence it once had a matching bronze lid, but it was stoppered with a makeshift piece of ceramic when it was hidden.

Even the bronze pot the treasure was buried in was expensive and special. Usually hoards were wrapped and buried in wood or pottery. The bronze container would have had significant value just on its own. There’s evidence it once had a matching bronze lid, but it was stoppered with a makeshift piece of ceramic when it was hidden.

Based on the date range of the coins and the mixture of Caliphate and Byzantine mintings, archaeologists postulate that the vase was buried at the end of the Islamic period during the wars of the First Crusade in the late 11th and early 12th century. King Baldwin I of Jerusalem had conquered his crown in July 1100 and quickly stuffed more cities under his shiny new monarchical belt. Cesarea fell on May 17th, 1101. The city founded by Herod the Great was important under Roman, Byzantine and Caliphate rule, a prosperous center of trade with public fountains and gardens. When it was conquered by the crusaders, it had a majority Muslim population many of whom fled the town to avoid a sticky fate.

Based on the date range of the coins and the mixture of Caliphate and Byzantine mintings, archaeologists postulate that the vase was buried at the end of the Islamic period during the wars of the First Crusade in the late 11th and early 12th century. King Baldwin I of Jerusalem had conquered his crown in July 1100 and quickly stuffed more cities under his shiny new monarchical belt. Cesarea fell on May 17th, 1101. The city founded by Herod the Great was important under Roman, Byzantine and Caliphate rule, a prosperous center of trade with public fountains and gardens. When it was conquered by the crusaders, it had a majority Muslim population many of whom fled the town to avoid a sticky fate.

According to contemporary accounts, most of the inhabitants of Caesarea were massacred by the army of Baldwin I, king of the recently created Kingdom of Jerusalem.

“The cache is a silent testimony to one of the most dramatic events in the history of Caesarea – the violent conquest of the city by the Crusaders. Someone hid their fortune, hoping to retrieve it – but never returned,” the archaeologists said. “It is reasonable to assume that the treasure’s owner and his family perished in the

massacre or were sold into slavery, and therefore were not able to retrieve their gold,” they added.

The cache constituted a small fortune, since at the time just one or two of these coins were equivalent to the annual salary of a simple farmer, said Robert Kool, an [Israel Antiquities Authority] coin expert.

The most recent coin in the hoard is one of the Byzantine coins of Michael II Doukas, minted in the last year of his reign. The dinars have not been cleaned yet. Their inscriptions will provide precise dates.

For a brief period in honor of Hanukkah and the traditional gift of “gelt,” gold coins, the hoard is on display at the Caesarea Port. The exhibition ends when the last Hanukkah candle goes out and the find will continue to be conserved, stabilized and studied.