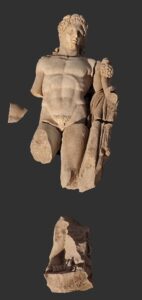

A larger-than-life statue of young Hercules has been found in the Greek city of Philippi. It dates to the 2nd century A.D. and is in unusually good condition despite suffering some damage. The club and the right arm are fragmented, and the right leg below the thigh is missing, but the head is intact, as are the torso and the tell-tale skin of the Nemean Lion. On top of his abundant mane of curls is a wreath of vine leaves tied around his head by a band that dangles down his neck and shoulders.

A larger-than-life statue of young Hercules has been found in the Greek city of Philippi. It dates to the 2nd century A.D. and is in unusually good condition despite suffering some damage. The club and the right arm are fragmented, and the right leg below the thigh is missing, but the head is intact, as are the torso and the tell-tale skin of the Nemean Lion. On top of his abundant mane of curls is a wreath of vine leaves tied around his head by a band that dangles down his neck and shoulders.

Originally founded as Crenides by colonists from the island of Thassos in 360 B.C., the town was conquered by Philip II, King of Macedon, and refounded in 356 BC as Philippi. It leapt into prominence thanks to its neighboring gold mines and important position on the royal route crossing Macedonia. Little remains of the Greek city today. It is famed as the site of the final battle between the armies of Caesar’s partisans Octavian and Mark Antony and those of his assassins Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus in 42 B.C. Philippi prospered under the Roman Empire, continuing through the fall of the Western Empire and, centuries later, the fall of Byzantine Empire. It was abandoned only after the Ottoman conquest of the 14th century.

The team of students and archaeologists from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki discovered the statue on the eastern side of one of the ancient city’s main thoroughfares at the point where it intersected with another major axis stretching north. Where the two streets met they widened into a square. There was a large structure on the square, likely a fountain, which survives only in fragments. The Hercules statue was the piece de resistance of this central structure.

The team of students and archaeologists from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki discovered the statue on the eastern side of one of the ancient city’s main thoroughfares at the point where it intersected with another major axis stretching north. Where the two streets met they widened into a square. There was a large structure on the square, likely a fountain, which survives only in fragments. The Hercules statue was the piece de resistance of this central structure.

The fountain/building is much younger than the statue that adorned it. It is Byzantine, dating to the 8th or 9th century A.D. They simply reused a piece of local statuary that was still in good shape to decorate the square.

The fountain/building is much younger than the statue that adorned it. It is Byzantine, dating to the 8th or 9th century A.D. They simply reused a piece of local statuary that was still in good shape to decorate the square.

We know from the sources as well as from the archaeological data that in Constantinople statues from the classical and Roman period adorned buildings and public spaces until the late Byzantine period.

This find demonstrates the way public spaces were decorated in the important cities of the Byzantine Empire, including Philippi.