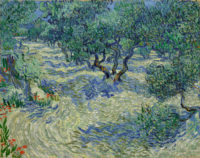

Conservators have discovered the body of a definitely deceased grasshopper resting in disarticulated peace among Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Trees. Mary Shafter at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, was examining the work under a microscope as part of a research project for the upcoming catalogue of the museum’s collection of 104 French paintings when she spotted the little guy entombed in the deadly embrace of van Gogh’s thick impasto in the shadow of the first olive tree on the right. At first she couldn’t tell what it was; she thought it might be the leaf debris or an imprint left by leaf on the paint when it was still wet. A closer inspection at the foreign body revealed that it had a head (a decapitated one) and was animal, not vegetable.

Conservators have discovered the body of a definitely deceased grasshopper resting in disarticulated peace among Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Trees. Mary Shafter at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, was examining the work under a microscope as part of a research project for the upcoming catalogue of the museum’s collection of 104 French paintings when she spotted the little guy entombed in the deadly embrace of van Gogh’s thick impasto in the shadow of the first olive tree on the right. At first she couldn’t tell what it was; she thought it might be the leaf debris or an imprint left by leaf on the paint when it was still wet. A closer inspection at the foreign body revealed that it had a head (a decapitated one) and was animal, not vegetable.

Van Gogh liked to paint out of doors, en plein air, as the French (and art historians) call it. Conservators working on his paintings often find leaves, sand, specks of dirt, even small bugs embedded in the canvas. Grasshoppers are not so common. The members of the Nelson-Atkins team were excited by the grasshopper find, and at the prospect of the creature adding new information to the record about when Van Gogh painted Olive Trees. The general date is known, 1889, which was a troubled time for the artist. The year before he’d had his massive break-up out with his former bestie Gauguin followed in short order by the ear cutting incident. In 1889 Van Gogh checked himself into the asylum at the Monastery Saint-Paul de Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence and remained there into 1890. The team hoped that if the grasshopper’s date of death could be identified from its stage in the growth/reproductive cycle or seasonal changes, then they might be able to conclusively determine whether Van Gogh painted Olive Trees during his stay in the mental health ward.

Paleoentomologist Dr. Michael S. Engel of the University of Kansas and American Museum of Natural History in New York City, came to their aid. He observed the insect under the microscope and realized that it was incomplete. The scattered body parts were missing the thorax and abdomen. He also was able to discern no sign of movement in the paint where the grasshopper’s bits were embedded, which means it was dead and dismembered before it hit the wet paint. This grasshopper was not pining for the fjords anymore by the time it landed on its eternal resting canvas. It therefore had nothing to contribute to the dating of its now thoroughly glamorous coffin.

Paleoentomologist Dr. Michael S. Engel of the University of Kansas and American Museum of Natural History in New York City, came to their aid. He observed the insect under the microscope and realized that it was incomplete. The scattered body parts were missing the thorax and abdomen. He also was able to discern no sign of movement in the paint where the grasshopper’s bits were embedded, which means it was dead and dismembered before it hit the wet paint. This grasshopper was not pining for the fjords anymore by the time it landed on its eternal resting canvas. It therefore had nothing to contribute to the dating of its now thoroughly glamorous coffin.

So the trapped grasshopper came to nothing, new data-wise, but it’s still a thrilling little slice of Van Gogh’s process frozen in time. He was deeply passionate about capturing life in movement in its natural setting. In one letter to his brother Theo from 1885, he went off on an extended rant about artists who reuse the same old backdrops, tableaux vivants, orientalist and heroic themes, rehashed styles, even models in their studio set pieces, how phony and lifeless their depictions were. He named names too.

Perhaps you think that I’m wrong to comment on this — but — I’m so gripped by the thought that all these exotic paintings are painted in THE STUDIO. But just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself! Then all sorts of things like the following happen — I must have picked a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand &c. — not to mention that, when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them &c. Not to mention that when one arrives on the heath after a couple of hours’ walk in this weather, one is tired and hot. Not to mention that the figures don’t stand still like professional models, and the effects that one wants to capture change as the day wears on.

That passage, which is not really a complaint so much as a recognition of how valuable working outdoors was to him despite the million irritants, explains exactly how the grasshopper likely got into the paint. He was either blown onto the wet canvas by wind or perhaps got stuck on it when Van Gogh lugged the large, heavy painting back home.

Visitors to the museum have been fascinated by the find. The grasshopper bits are less than half an inch in size and can’t possible compete with the density, vibrancy and complexity of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes, but that hasn’t stopped visitors from doing their utmost to spot the wee body parts in the shadow of that tree.

While the grasshopper becomes an engaging topic for museum visitors, more significant research on Olive Trees is underway. Analysis by Mellon Science Advisor John Twilley confirms that van Gogh used a type of red pigment that gradually faded over time. These findings suggest that areas where van Gogh employed this red, either alone or mixed with other colors, appear slightly different today than when the painting was completed.

“Color relationships were central to van Gogh’s practice,” said Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator of European Art. “Since we now know that portions of the canvas where van Gogh employed this particular red pigment have faded, those color relationships are altered.”

The artist’s letters often referred to his works by their dominant colors, which means the more recent changes in appearance can present uncertainty as to which painting van Gogh alluded to in his descriptions. With funding through the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Endowment for Scientific Research in Conservation, more research is being conducted to evaluate the impact of these color shifts. The research is expected to clarify the original appearance of Olive Trees and to offer a clearer understanding of its place within van Gogh’s series of works on this theme.