Archaeologists have discovered evidence in the bones 19th century Dutch farmers that the traditional wooden clogs that are now ubiquitous on key chains and souvenir stands but were once ubiquitous on human feet caused permanent osteological damage. An international team of osteoarchaeologists from Leiden University and Western University (Ontario, Canada) discovered the tell-tale bones in 2011 during an excavation of a historic church cemetery in the village of Middenbeemster, Netherlands, that was being relocated.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence in the bones 19th century Dutch farmers that the traditional wooden clogs that are now ubiquitous on key chains and souvenir stands but were once ubiquitous on human feet caused permanent osteological damage. An international team of osteoarchaeologists from Leiden University and Western University (Ontario, Canada) discovered the tell-tale bones in 2011 during an excavation of a historic church cemetery in the village of Middenbeemster, Netherlands, that was being relocated.

Beemster was a rural farming community, a dairy farming community, mainly, and the team was hoping to gather previously unrecorded data about the diet, health, common injuries, illnesses and general health of country folk in the 19th century Netherlands using osteobiographical and paleopathological analysis as well as stable isotope analysis (to find out what they ate) and mass spectrometry. There’s a significant body of work that’s already been done on the inhabitants of Dutch cities, but the rural areas have been little studied so this was a unique and important opportunity.

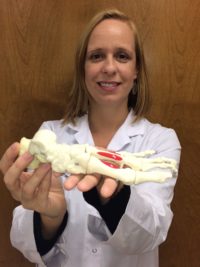

They were able to analyze 500 skeletons, most them very well-preserved, of adult women, men and children. Out of those remains, 130 complete feet were found. Bio-archaeologist and Western University Anthropology professor Andrea Waters-Rist examined the feet bones and found a consistent pattern among them: they presented a rare type of bone lesion called osteochondritis dissecans (OD) which looks like a chip or divot has been chiseled out of the bone. She didn’t even have to use a microscope to see them. The missing chunks at the joints were clearly visible to the naked eye.

They were able to analyze 500 skeletons, most them very well-preserved, of adult women, men and children. Out of those remains, 130 complete feet were found. Bio-archaeologist and Western University Anthropology professor Andrea Waters-Rist examined the feet bones and found a consistent pattern among them: they presented a rare type of bone lesion called osteochondritis dissecans (OD) which looks like a chip or divot has been chiseled out of the bone. She didn’t even have to use a microscope to see them. The missing chunks at the joints were clearly visible to the naked eye.

In the wider population, OD is found in less than one percent of individuals and the lesions affect various bones, very rarely those in the foot. A whopping 13% of the good folks from the Middenbeemster cemetery, on the other hand, had it and they only had it in their feet. Part of the cause was likely the hard physical labor involved in traditional farming, both inside the home and outside of it, but a lot of people fed their families with backbreaking work and they didn’t have craters in their feet bones. Researchers concluded that it was likely a combination of heavy labour and repetetive stress on certain areas of the feet cause by the iconic “klompen” (which are still worn today, btw, particularly in rural areas).

For farmers, the clogs would have been very useful shoes, as they were affordable, kept their feet dry and, if stuffed with straw, quite warm. As such, they would have been worn for most uses. As the clogs have a stiff sole, they could have amplified the stresses associated with farm work and travelling by foot.

That combination of hard work, while wearing klompen, day-in and day-out, caused the bone chip to form, Water-Rist explained.

“The sole is very hard and inflexible, which constrains the entire foot and we think because the footwear wasn’t good at absorbing any kind of shock, it was transferring into the foot and into the foot bones. It’s not very common in the foot. They were doing something different that we haven’t seen before,” she said.

Since these farmers lived in a time before industrialization, manual labour was more taxing on their body. Oftentimes the klompen was used as a tool for kicking down fences or pushing in a shovel – all tasks later made easier by machinery.

The results of the study of the klompen-related OD lesions have been published in the International Journal of Paleopathology but it’s behind a paywall so you’ll need a subscription or an institutional connection or to pay $31.50 to read it.