The remains of the Temple of Mithras discovered under central London’s Walbrook Square in 1954 has returned to its original location and it looks great, better than it has in 50+ years. The temple, first built around 240 A.D., was unearthed by archaeologists William Francis Grimes and Audrey Williams in the very last days of a two-year archaeological survey of the site before the construction of new office buildings. The temple was identified as a Mithraeum when the beautifully sculpted head of Mithras, complete with Phrygian cap, was found. A reporter happened to be there and took a picture. Mithras’ beauty caused a sensation and almost half a million people came to visit the excavation.

The remains of the Temple of Mithras discovered under central London’s Walbrook Square in 1954 has returned to its original location and it looks great, better than it has in 50+ years. The temple, first built around 240 A.D., was unearthed by archaeologists William Francis Grimes and Audrey Williams in the very last days of a two-year archaeological survey of the site before the construction of new office buildings. The temple was identified as a Mithraeum when the beautifully sculpted head of Mithras, complete with Phrygian cap, was found. A reporter happened to be there and took a picture. Mithras’ beauty caused a sensation and almost half a million people came to visit the excavation.

The ensuing public outcry forced the city to abandon its original plan — the demolition of the temple to make way for ugly concrete squares of cheap mid-century offices — and come up with a compromise solution. The excavation would be extended and once the archaeologists were done, the temple remains would be removed and reinstalled a few hundred feet away at ground level so the public could enjoy it. In 1962, plan B was completed and London’s Mithraeum was reconstructed on an empty patch of

The ensuing public outcry forced the city to abandon its original plan — the demolition of the temple to make way for ugly concrete squares of cheap mid-century offices — and come up with a compromise solution. The excavation would be extended and once the archaeologists were done, the temple remains would be removed and reinstalled a few hundred feet away at ground level so the public could enjoy it. In 1962, plan B was completed and London’s Mithraeum was reconstructed on an empty patch of  land on Victoria Street. The objects discovered would go the Museum of London, except for the incredibly rare surviving wood benches and joists from the temple’s original floor, preserved in the waterlogged soil where the lost Walbrook River had once coursed. They were thrown out like so much trash.

land on Victoria Street. The objects discovered would go the Museum of London, except for the incredibly rare surviving wood benches and joists from the temple’s original floor, preserved in the waterlogged soil where the lost Walbrook River had once coursed. They were thrown out like so much trash.

Unfortunately plan B was poorly executed. Modern concrete was used to patch up holes and build up some of the lost masonry. The temple was not installed in its original configuration and was basically unrecognizable compared to how it had looked in situ. Things did not improve as the city grew up around it, leaving it looking like a random, weird, squat rectangle of brick and mortar benches.

In 2010, the Walbrook Square site was bought by Bloomberg LP who planned to build a grand new European HQ there. Of course they knew about the potential for archaeological remains under the site, so an in depth survey was commissoned and this time the soggy muck of the lost Walbrook River turned in an even more spectacular feat of preservation. The excavation unearthed entire city streets, large slices of Roman London from its earliest days in 40 A.D. to the final withdrawal of Roman troops in the 5th century. Wood streets, wood walls, wood wells, a wood door, thousands and thousands of assorted objects made of leather, wood, textiles as well as metal and stone. The oldest dated writing ever found in Britain was discovered on one of hundreds of Roman wood tablets from the Bloomberg dig.

In 2010, the Walbrook Square site was bought by Bloomberg LP who planned to build a grand new European HQ there. Of course they knew about the potential for archaeological remains under the site, so an in depth survey was commissoned and this time the soggy muck of the lost Walbrook River turned in an even more spectacular feat of preservation. The excavation unearthed entire city streets, large slices of Roman London from its earliest days in 40 A.D. to the final withdrawal of Roman troops in the 5th century. Wood streets, wood walls, wood wells, a wood door, thousands and thousands of assorted objects made of leather, wood, textiles as well as metal and stone. The oldest dated writing ever found in Britain was discovered on one of hundreds of Roman wood tablets from the Bloomberg dig.

The Bloomberg coporation has far deeper pockets than the small potatoes real estate developers in 1954, so it made ambitious plans to include all of these archaeological marvels in an underground display space in the Bloomberg. Not only would Roman London’s many layers be viewable to the public, but it would foot the bill to rescue the poor, benighted reconstructed temple remains from their incongruous street-level location and overmortared neglect. The temple

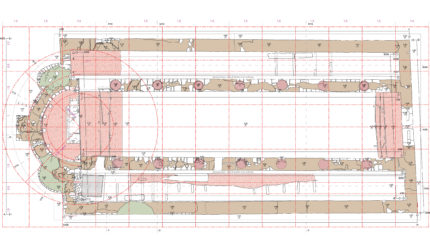

The Bloomberg coporation has far deeper pockets than the small potatoes real estate developers in 1954, so it made ambitious plans to include all of these archaeological marvels in an underground display space in the Bloomberg. Not only would Roman London’s many layers be viewable to the public, but it would foot the bill to rescue the poor, benighted reconstructed temple remains from their incongruous street-level location and overmortared neglect. The temple  would return to its original location, dismantled, cleaned of modern interpolations and reinstalled in situ as it had once been. There it would have the chance to be seen in its proper context, safe from the elements, and would even be reunited with another piece of the temple that was discovered during the recent excavation.

would return to its original location, dismantled, cleaned of modern interpolations and reinstalled in situ as it had once been. There it would have the chance to be seen in its proper context, safe from the elements, and would even be reunited with another piece of the temple that was discovered during the recent excavation.

Tha planned opening date for the new Bloomberg building and its greatest of all basements was 2017, and right on schedule, the London Mithraeum at Bloomberg SPACE opens November 14th.

Tha planned opening date for the new Bloomberg building and its greatest of all basements was 2017, and right on schedule, the London Mithraeum at Bloomberg SPACE opens November 14th.

Michael Bloomberg, the founder of the company, said they were stewards of the ancient site and its artefacts. “London has a long history as a crossroads for culture and business, and we are building on that tradition.”

The Mithraeum incorporates a new daylit art gallery at ground level with an opening installation, Another View from Nowhen, by the Dublin artist Isabel Nolan. A huge glass case displays more than 600 of the 14,000 objects found on the site, including a wooden door, a hobnailed sandal, a tiny gladiator’s helmet carved in amber, and a wooden tablet with the oldest record of a financial transaction from Britain.

You can’t just walk in to see this archaeological treasure. Entrance is free of charge, but you must book first to guarantee entry. Click this link to book tickets, and have a poke around the website while you’re at it because it’s really very good. They worked hard to collect images and footage of the 1950s excavation and have incorporated them effectively on the site.

You can’t just walk in to see this archaeological treasure. Entrance is free of charge, but you must book first to guarantee entry. Click this link to book tickets, and have a poke around the website while you’re at it because it’s really very good. They worked hard to collect images and footage of the 1950s excavation and have incorporated them effectively on the site.