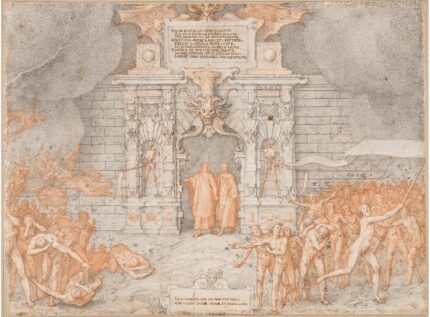

This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, diplomat, poet and author of the seminal Divine Comedy. In honor of the occasion, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence has digitized a rare set of illustrations of the Divine Comedy in high definition and made them available online for the first time. The 88 drawings illustrating the Divine Comedy were created by Mannerist painter Federico Zuccari in the late 16th century and few of them have ever been exhibited, and even then only twice, once in 1865 and once in 1993. Very little known but beloved by Dante scholars, the Zuccari drawings are widely considered the most important illustrations of Dante’s masterpiece until Gustave Doré’s burst on the scene in 1861.

This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, diplomat, poet and author of the seminal Divine Comedy. In honor of the occasion, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence has digitized a rare set of illustrations of the Divine Comedy in high definition and made them available online for the first time. The 88 drawings illustrating the Divine Comedy were created by Mannerist painter Federico Zuccari in the late 16th century and few of them have ever been exhibited, and even then only twice, once in 1865 and once in 1993. Very little known but beloved by Dante scholars, the Zuccari drawings are widely considered the most important illustrations of Dante’s masterpiece until Gustave Doré’s burst on the scene in 1861.

Zuccari (also spelled Zuccaro) is best known today for having completed the frescoes inside the dome of Florence’s cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore (Vasari started them), but he was famous in his time and very much in demand by the crowned heads of Europe. His patrons included several popes, Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots and Philip II of Spain. He was working King Philip, designing frescoes for the El Escorial palace north of Madrid, when he embarked on his illustrations of the Divine Comedy in 1586. It took him two years to complete all 88 drawings.

Zuccari (also spelled Zuccaro) is best known today for having completed the frescoes inside the dome of Florence’s cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore (Vasari started them), but he was famous in his time and very much in demand by the crowned heads of Europe. His patrons included several popes, Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots and Philip II of Spain. He was working King Philip, designing frescoes for the El Escorial palace north of Madrid, when he embarked on his illustrations of the Divine Comedy in 1586. It took him two years to complete all 88 drawings.

They entered the collection of the Uffizi in 1738, donated by Anna Maria  Luisa de’ Medici, Electress Palatine, less than a year after she saved the Medici’s art collection for Florence in perpetuity. Today the pages are extremely fragile. They are kept in a dark, temperature and moisture-controlled environment and can only be exposed every five years. That makes them all but inaccessible to scholars as well as to the public, which is why the Uffizi has chosen to digitize them in their entirety so the works can be studied without putting them at risk.

Luisa de’ Medici, Electress Palatine, less than a year after she saved the Medici’s art collection for Florence in perpetuity. Today the pages are extremely fragile. They are kept in a dark, temperature and moisture-controlled environment and can only be exposed every five years. That makes them all but inaccessible to scholars as well as to the public, which is why the Uffizi has chosen to digitize them in their entirety so the works can be studied without putting them at risk.

The museum has compiled the digitized Zuccardi illustrations into a journey mirroring their original context in a bound volume. Zuccardi’s illustrations are on the right page; on the left are the verses from the Divine Comedy being illustrated, plus short synopses written by Zuccardi himself. The Zuccardi exhibition is currently only available in Italian, but an English version is imminent. Meanwhile, you can peruse the illustrations in each of three cantos —Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. Already available in English is an exhibition exploring Dante’s connection to the visual arts and how the poet and his masterpiece were represented.