Penn Museum archaeologists have discovered the tomb of a previously unknown pharaoh from Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, ca. 1650 B.C., in Abydos. The new pharaoh’s name is Woseribre Senebkay and his tomb was found next to that of 13th Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep I last week.

Penn Museum archaeologists have discovered the tomb of a previously unknown pharaoh from Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, ca. 1650 B.C., in Abydos. The new pharaoh’s name is Woseribre Senebkay and his tomb was found next to that of 13th Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep I last week.

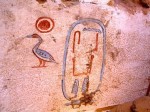

The tomb of Senebkay consists of four chambers with a decorated limestone burial chamber. The burial chamber is painted with images of the goddesses Nut, Nephthys, Selket, and Isis flanking the king’s canopic shrine. Other texts name the sons of Horus and record the king’s titulary and identify him as the “king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Woseribre, the son of Re, Senebkay.”

Senebkay’s tomb was badly plundered by ancient tomb robbers who had ripped apart the king’s mummy as well as stripped the pharaoh’s tomb equipment of its gilded surfaces. Nevertheless, the Penn Museum archaeologists recovered the remains of king Senebkay amidst debris of his fragmentary coffin, funerary mask, and canopic chest. Preliminary work on the king’s skeleton of Senebkay by Penn graduate students Paul Verhelst and Matthew Olson (of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations) indicates he was a man of moderate height, ca. 1.75 m (5’10), and died in his mid to late 40s.

This is a highly significant discovery because it confirms that there was an independent ruling dynasty in Abydos contemporary with the dynasties ruling northern and southern Egypt. The northern 15th Dynasty rulers were Hyksos, invaders from what are today Syria, Lebanon and Israel. Down south in Thebes the 16th Dynasty was native Egyptian. Right around the time the Kingdom of Abydos ended, ca. 1600 B.C., the Thebans began a war to expel the occupiers in the north and re-unify Egypt. The war lasted 50 years. The Hyksos were defeated and the New Kingdom founded.

This is a highly significant discovery because it confirms that there was an independent ruling dynasty in Abydos contemporary with the dynasties ruling northern and southern Egypt. The northern 15th Dynasty rulers were Hyksos, invaders from what are today Syria, Lebanon and Israel. Down south in Thebes the 16th Dynasty was native Egyptian. Right around the time the Kingdom of Abydos ended, ca. 1600 B.C., the Thebans began a war to expel the occupiers in the north and re-unify Egypt. The war lasted 50 years. The Hyksos were defeated and the New Kingdom founded.

This Abydos Dynasty may have been a kind of buffer state between the two. They used the Anubis-Mountain area of South Abydos as a royal necropolis conveniently located next to the richer tombs of Middle Kingdom pharaohs like Sobekhotep I. There are approximately 16 tombs from the Abydos dynasty in the necropolis which range in date from 1650–1600 B.C., making Senebkay one of the first to be buried.

The archaeological team has located 10 of the possible 16 tombs. Six of them have been excavated; four have been detected by ground penetrating radar but not entered yet. Four of the six explored tombs had been gutted by ancient looters, but tomb number five had the remains of Senebkay. The cedar canopic chest that held his organs was, shall we say, borrowed from Sobekhotep I’s tomb. We know this because his name is still on it, although Senebkay’s people tried to obscure the name by gilding the chest.

The archaeological team has located 10 of the possible 16 tombs. Six of them have been excavated; four have been detected by ground penetrating radar but not entered yet. Four of the six explored tombs had been gutted by ancient looters, but tomb number five had the remains of Senebkay. The cedar canopic chest that held his organs was, shall we say, borrowed from Sobekhotep I’s tomb. We know this because his name is still on it, although Senebkay’s people tried to obscure the name by gilding the chest.

That’s not the only piece of Sobekhotep’s funerary regalia to get recycled. The 60-ton red quartzite sarcophagus originally in his tomb was discovered in the sixth tomb of the Abydos kings. Archaeologists haven’t yet found a cartouche or any other information that might identify the pharaoh who pilfered the massive sarcophagus, but they think that wasn’t the first time it was re-used by the Abydos rulers.

That’s not the only piece of Sobekhotep’s funerary regalia to get recycled. The 60-ton red quartzite sarcophagus originally in his tomb was discovered in the sixth tomb of the Abydos kings. Archaeologists haven’t yet found a cartouche or any other information that might identify the pharaoh who pilfered the massive sarcophagus, but they think that wasn’t the first time it was re-used by the Abydos rulers.

The short-lived dynasty fills in a hole in the Turin King List. The ancient papyrus from the reign of Ramses II (ca. 1200 B.C.) has been damaged. There are two partial king names that read as “Woser…re” that top a list that originally had more than a dozen king names but now all have been lost.

The Abydos kings were nowhere near as wealthy and powerful as their neighbors to north and south. Senebkay’s limestone tomb is small and poorly appointed. The painting is colorful and lovely, but it’s fairly unsophisticated and sparse. This is probably why they recycled older pharaoh’s fancy gear.

The Abydos kings were nowhere near as wealthy and powerful as their neighbors to north and south. Senebkay’s limestone tomb is small and poorly appointed. The painting is colorful and lovely, but it’s fairly unsophisticated and sparse. This is probably why they recycled older pharaoh’s fancy gear.

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time archaeologists have stumbled on these tombs. Legendary Egyptologist Flinders Petri unearthed four of the tomb in 1901-1902, but he didn’t recognize them as royal or even high-status tombs because of how modest they are.

The excavation season is over for now, but team leader Josef Wegner of the University of Pennsylvania believes they will discover much more about the Abydos dynasty when they return in the spring. King’s tombs are usually flanked by the tombs of queens, courtiers and other important officials.