Using specimens from the Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum, researchers from the at McMaster University and the University of Sydney have mapped the genome of the 19th century cholera bacterium that killed millions of people during the 1800s. There are two genetically distinct biotypes of the main cholera strain, Vibrio cholerae. One of them, the classical, was dominant in the 19th century only to be overtaken by the other, El Tor, in the 20th century. Since cholera does its damage by colonizing the intestines rather than the blood, it doesn’t leave behind traces of its DNA in the teeth or bones. You can only find cholera bacteria in the intestinal soft tissues, and obviously they decay very quickly so although many cholera burial sites are known, there’s no use attempting to extract cholera DNA from historical remains.

Using specimens from the Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum, researchers from the at McMaster University and the University of Sydney have mapped the genome of the 19th century cholera bacterium that killed millions of people during the 1800s. There are two genetically distinct biotypes of the main cholera strain, Vibrio cholerae. One of them, the classical, was dominant in the 19th century only to be overtaken by the other, El Tor, in the 20th century. Since cholera does its damage by colonizing the intestines rather than the blood, it doesn’t leave behind traces of its DNA in the teeth or bones. You can only find cholera bacteria in the intestinal soft tissues, and obviously they decay very quickly so although many cholera burial sites are known, there’s no use attempting to extract cholera DNA from historical remains.

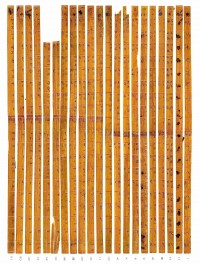

That’s where the Mütter Museum’s remarkable collection comes into play. Founded in 1858 by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia around Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter’s collection of medical specimens, tools and oddities, the Mütter Museum contains a number of preserved specimens of intestines of cholera victims. One specimen, labeled 3090.13, holds a chunk of intestine from a man who died in the cholera epidemic that struck Philadelphia in May of 1849, killing 340,045 people in the city by the time it was finished. (The 1849 epidemic killed a total of 1,772,193 around the country.) The specimen was collected by Dr. John Neill for a study on the effects of cholera on the lining of the intestine. He delivered a report on his findings to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and the specimens he displayed became part of the Mütter Museum collection a decade later.

Researchers took a small sample of the intestinal specimen and were able to extract sufficient DNA traces to map the entire genome of the bacterium. They were able to confirm that it was the classical biotype that spread in the 1849 epidemic, and that indeed it was responsible for five of the seven major cholera outbreaks since 1817. (Before this study only the culprit of the most recent two outbreaks was identified as El Tor.)

Researchers took a small sample of the intestinal specimen and were able to extract sufficient DNA traces to map the entire genome of the bacterium. They were able to confirm that it was the classical biotype that spread in the 1849 epidemic, and that indeed it was responsible for five of the seven major cholera outbreaks since 1817. (Before this study only the culprit of the most recent two outbreaks was identified as El Tor.)

Using a sophisticated technique to extract, purify and enrich fragments of the pathogen’s DNA, the team collected precious genomic data, which answered many unresolved questions.

The researchers identified “novel genomic islands”, or genome regions that don’t occur in current strains. In addition, a well-known genic region involved in toxicity of the pathogen (a sequence called “CTX”) occurs more times in the ancient strain than in its modern descendants.

This may mean that this strain was more virulent, say researchers, but further testing will be needed.

Regarding the origins, the team’s calculations show that the classical strain and El Tor co-existed in humans and estuaries for many centuries, potentially thousands of years prior to the 19th century pandemics, and emerged as a full-blown infection in humans in the early 1800’s.

That’s not to say the 19th century is the first time the cholera bacterium made humans sick. Scientists believe the strains co-evolved in a water column in the Bay of Bengal for thousands of years before crossing over into people’s intestines around 5,000 years ago. This was a time of major transition, when the climate in Indian was drying up and causing formerly nomadic peoples to settle around water sources, farm the land and form communities. The population expanded and with more people comes more poop and contaminated water which then creates novel forms and bacteria and back and forth in the dizzying, endless waltz between pathogen and humanity.

This discovery underscores the importance of what may seem like dusty old useless pieces of people bobbing in specimen jars still held in museums, universities and hospitals all over the world. They may hold the key to the history of past epidemics and provide invaluable insight into diseases that still afflict millions of people.

It’s great to see the Mütter Museum still breaking new ground in medical research 156 years after it was founded for that very purpose. I think they should have a sale on their cholera plushie to celebrate their role in the mapping of the genome of its less adorable cousin.

It’s great to see the Mütter Museum still breaking new ground in medical research 156 years after it was founded for that very purpose. I think they should have a sale on their cholera plushie to celebrate their role in the mapping of the genome of its less adorable cousin.