It’s the first month of the new year and we already have a fine addition to my collection of Pompeii metaphors used to describe archaeological sites that are nothing at all like Pompeii. This time it’s the town of Cerreto Sannita in the southern Italian region of Campania being made to wear the Pompeii colors. The connection is that both cities were struck by a horrific cataclysm, but the comparisons pretty much end there. The town was reduced to rubble by an earthquake in the 17th century and a new Cerreto Sannita was built next to the ruins (to distinguish it from the new town, the site of the medieval ruins is called Cerreto antica). Little of the old city is visible today. Whatever is left is underground.

To ferret out the remnants of Cerreto antica, archaeologists have deployed a drone named Indiana Jones. With its onboard laser and videocamera, Indiana Jones is surveying the site above and below ground. Indiana’s lidar data will be the jumping off point for a hands-on archaeological excavation. The site will then be secured and any structures exposed will be stabilized. Artifacts recovered during the dig will be catalogued, and finally, the drone and dig information will be used to create a 3D model of the complete site. The “Medieval Cerreto” model won’t be just a virtual recreation, but a starting point for exploring the terrain, history and traditions of the town.

To ferret out the remnants of Cerreto antica, archaeologists have deployed a drone named Indiana Jones. With its onboard laser and videocamera, Indiana Jones is surveying the site above and below ground. Indiana’s lidar data will be the jumping off point for a hands-on archaeological excavation. The site will then be secured and any structures exposed will be stabilized. Artifacts recovered during the dig will be catalogued, and finally, the drone and dig information will be used to create a 3D model of the complete site. The “Medieval Cerreto” model won’t be just a virtual recreation, but a starting point for exploring the terrain, history and traditions of the town.

The Cerreto project is part of an initiative funded by Ministry of Education, Universities and Research that seeks to addresses issues of structural security while developing methods to integrate the protection, oversight and sustainable redevelopment of historical sites. The aim is to bring added safety and value to sites of cultural interest in seismically active areas, and boy is this area seismically active.

The towns, like Cerreto Sannita, in the environs of Benevento have a long, storied past of earthquake-induced upheaval. In fact, Cerreto itself once prospered mightily from an earthquake that drove residents out of the nearby town of Telesia. For centuries a regional administrative center under Lombard and Norman authorities, Telesia was seat of a bishopric from the 4th century A.D. until a massive series of earthquakes struck the central Apennine regions for an incredible seven months, from January until September of 1349. Sinkholes and landslides filled up with stagnant water, soil became swampy and volcanic fissures that emanated carbon dioxide and sulfur fumes made the air close to unbreathable. Telesia was abandoned and much of the population moved to Cerreto.

The towns, like Cerreto Sannita, in the environs of Benevento have a long, storied past of earthquake-induced upheaval. In fact, Cerreto itself once prospered mightily from an earthquake that drove residents out of the nearby town of Telesia. For centuries a regional administrative center under Lombard and Norman authorities, Telesia was seat of a bishopric from the 4th century A.D. until a massive series of earthquakes struck the central Apennine regions for an incredible seven months, from January until September of 1349. Sinkholes and landslides filled up with stagnant water, soil became swampy and volcanic fissures that emanated carbon dioxide and sulfur fumes made the air close to unbreathable. Telesia was abandoned and much of the population moved to Cerreto.

This gave the town a major economic, political and demographic boost. In 1593, Bishop Cesare Bellocchi instituted the diocesan seminary in Cerreto Sannita. After his death two years later, the new bishop, Eugenio Savino, moved into a palace in Cerreto donated by a local nobleman and made it the new official seat of the diocese which was renamed the Diocese of Telese or Cerreto Sannita. The town was now an important religious center, replete with churches, monasteries and convents.

Karma struck on June 5th, 1688. Cerreto Sannita was the epicenter of an earthquake estimated by seismologists to have been more than 7.0 on the Richter Scale. More than 4,000 people, half the population of the town, died and the entire town was razed to the ground. Six days later, Bishop Giovanni Battista de Bellis wrote to the head of the Congregation for Bishops reporting on the disaster.

“I am forced, crying, to advise you of the horrific spectacle of desolation in this my diocese, for the earthquake that struck at five the night before Pentecost while I was left weeping for my misery and that of my people. … Telese from ancient times was abandoned and my predecessor bishops moved to Cerreto, already populous, and there built a church, extremely beautiful, and to this church they transferred the services of the Cathedral where 15 Canons officiated. In this land of Cerreto there was the Church of San Martino, parochial and collegial, with 11 Canons and the Archpriest. There was a monastery of Conventual friars, a distinguished place of study, a monastery of Capuchin friars, a convent of the Nuns of the Order of Saint Clair where there were 65 nuns and converts.

Now this land with the churches, monasteries and everything, in the time it takes to recite a Credo, collapsed all, all, all, without there remaining standing even one house to take refuge in, something that anyone who did not see it would scarce believe it.”

The response was sympathetic but laconic. The Bishop went over the Curia’s head and appealed straight to Pope Innocent XI, explaining how the entire town had been leveled, that only three small dwellings belonging to a potter had survived the quake at all, and their walls were either crumbling or about to collapse, listing the numbers of dead in every convent, monastery and church, and asking that Rome help with emergency funds. He received no response. Only with the election of Pope Alexander VIII, a man known for his magnanimity, in 1689 did the diocese receive financial support for the reconstruction of the cathedral.

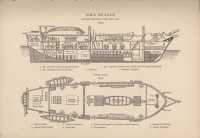

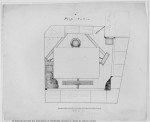

Unlike Telesia, Cerreto was not abandoned. It was rebuilt from scratch. Count Marzio Carafa stopped residents who were already beginning to rebuild their homes using the rubble and instead turned to royal engineer Giovanni Battista Manni to plan a town with particular attention to seismic stability. Also aided by his bother Marino and Bishop de Bellis, Marzio Carafa moved the city center downvalley onto a broad, low hill that was significantly more stable than the land the old town had been built on. It was all private property which the Count claimed through a sort of medieval version of eminent domain.

Unlike Telesia, Cerreto was not abandoned. It was rebuilt from scratch. Count Marzio Carafa stopped residents who were already beginning to rebuild their homes using the rubble and instead turned to royal engineer Giovanni Battista Manni to plan a town with particular attention to seismic stability. Also aided by his bother Marino and Bishop de Bellis, Marzio Carafa moved the city center downvalley onto a broad, low hill that was significantly more stable than the land the old town had been built on. It was all private property which the Count claimed through a sort of medieval version of eminent domain.

He also took out a loan of 3,000 ducats to build one and two-room houses that he sold to residents for manageable sums of 50 to 184 ducats. Since they had lost everything, the Count authorized his debt collector to extend loans for the purchase of the houses with interest-free repayments for three years and 6% interest the fourth. Eight years after the earthquake, the new town was complete and every resident owned his own new home with seismic design features like split support windows.

Inspired by Roman urbs, the new Cerreto Sannita had two major streets (decumani) parallel to each other with one-way traffic in opposite directions running down the length of the town and a number of small streets (cardini) connecting the two arteries. There were no defensive walls, no cramped and crooked alleys. It remains to this day one of the only surviving examples of a pure planned city from the late 17th century.