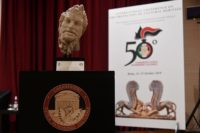

A marble head of Pan stolen 51 years ago has been returned to Italy. The statue head, which dates to the 1st-2nd century A.D., was looted in February 1968 from the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine hill. US Ambassador to Italy Lewis Eisenberg formally handed over the looted object to Culture Minister Dario Franceschini in a ceremony on Rome on Thursday.

A marble head of Pan stolen 51 years ago has been returned to Italy. The statue head, which dates to the 1st-2nd century A.D., was looted in February 1968 from the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine hill. US Ambassador to Italy Lewis Eisenberg formally handed over the looted object to Culture Minister Dario Franceschini in a ceremony on Rome on Thursday.

Carabinieri special investigators spotted the marble head in a California auction catalog in 2016 and notified their U.S. counterparts.

U.S. attache Armando Astorga said the piece entered the United States in the mid-2000s, after spending many years in private hands in Europe.

So far, the investigation has not determined the original thief.

The Farnese Gardens were built over the in-filled ruins of Tiberius’ palace by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III, in 1550. They were the first private botanical gardens in Europe, filled with rare plants imported from Africa and the Americas, grottos, aviaries, monumental gates, terraced balconies and staircases scaling the Palatine from the Campo Vaccino below. Alessandro Farnese’s collection of ancient statuary, assembled from finds on his own property and the acquisition of entire collections from other noble families, was installed in the botanical gardens.

The view from the garden included the Arch of Titus, the iconic three columns of the Temple of Castor of Pollux and the Basilica of Maxentius. In the 17th century the water supply to the Palatine was restored and the Farnese family expanded the garden to include fountains. Between the exotic plants, picturesque fountains, dramatic views and the Vatican museum-quality ancient sculptures, the Farnese Gardens became a popular stop for Grand Tourists of the moneyed classes.

The view from the garden included the Arch of Titus, the iconic three columns of the Temple of Castor of Pollux and the Basilica of Maxentius. In the 17th century the water supply to the Palatine was restored and the Farnese family expanded the garden to include fountains. Between the exotic plants, picturesque fountains, dramatic views and the Vatican museum-quality ancient sculptures, the Farnese Gardens became a popular stop for Grand Tourists of the moneyed classes.

The remains of the Roman and Imperial fora would be excavated in the 19th century, but by then the Farnese Gardens were almost as ruined as the great civic structures of the ancient city. When Antonio, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, the last Farnese of the patrilineal line died in 1731, Alessandro’s Palatine summer villa, botanical gardens and the greatest collection of ancient statuary assembled since antiquity passed into the hands of Antonio’s niece Elizabetta Farnese, Queen consort of King Philip V of Spain, and thence to her son Charles of Bourbon, soon to be king of Naples and the Two Sicilies. As absentee landowners, the Bourbon-Parmas neglected their Roman properties and by the mid-18th century the Farnese Gardens were already in decay. A century later, the villa and garden were largely in ruins.

The last King of the Two Sicilies, Francis II, sold the Farnese Gardens to Napoleon III of France. After the full Unification of Italy with Rome as its capital in 1870, the state bought the property and began to excavate it, seeking the remains of the ancient imperial palaces like the one Alessandro Farnese had so blithely filled in to make his garden. The archaeological site has been excavated off and on since then.

Just over a year after the head of Pan was stolen from the site, the Carabinieri Art Squad was founded on May 3rd, 1969. It was the first national police force division dedicated specifically to the protection of cultural heritage, anticipating by a year the UNESCO Convention combatting the illegal export and traffic in cultural artifacts. To mark the 50th anniversary of this important milestone in the fight against the illicit traffic in archaeological and artistic treasures, the Carabinieri are currently hosting an international conference on heritage protection. The head of Pan was repatriated on the opening day of the conference, a fitting celebration of the anniversary.