Ancient pearls have been discovered in fossil form going back to the Cretaceous Period (145-65 million years ago), but they don’t appear in the archaeological record until fairly recently. Conventional jeweler’s wisdom has it that the oldest archaeological pearl known is the 5000-year-old Jomon pearl, found in Japan and named after the semi-settled hunter-gatherer period of Japanese prehistory (ca. 14,000 B.C.-300 B.C.) to which it dates, but as so often happens, conventional wisdom is wrong. There isn’t much reliable information about the Jomon pearl that I was able to discover online, no academic research, no details about where it was found, just the same two sentences on page after page of “famous pearls” websites, but there are properly documented pearls that are far older than 5000 years.

According to Pearls: A Natural History, a gorgeously illustrated book written in conjunction with the American Museum of Natural History’s and The Field Museum’s Pearls exhibit that I had the great fortune to see when it was on the road in 2003, the oldest pearls found connected to human habitation have been found in Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites in Mesopotamia and Arabia. Some of them were found in shell midden piles, discards from harvests of freshwater mollusks. Two perforated pearls dating to between 3700 and 3400 B.C. were found grasped in the right hands of one male and one female skeleton buried facing the sea at the Ras al-Hamra site in Oman.

According to Pearls: A Natural History, a gorgeously illustrated book written in conjunction with the American Museum of Natural History’s and The Field Museum’s Pearls exhibit that I had the great fortune to see when it was on the road in 2003, the oldest pearls found connected to human habitation have been found in Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites in Mesopotamia and Arabia. Some of them were found in shell midden piles, discards from harvests of freshwater mollusks. Two perforated pearls dating to between 3700 and 3400 B.C. were found grasped in the right hands of one male and one female skeleton buried facing the sea at the Ras al-Hamra site in Oman.

Excavations in the early 2000s by the British Archaeological Expedition to Kuwait unearthed a pearl dating to around 5000 B.C. at the As-Sabiyah site inland from the northern edge of Kuwait Bay. The pearl is pierced through so clearly its intended use was decorative. A number of mother-of-pearl beads, buttons and other kinds of shell jewelry were also found, evidence of the long tradition of pearling in the Persian Gulf.

Excavations in the early 2000s by the British Archaeological Expedition to Kuwait unearthed a pearl dating to around 5000 B.C. at the As-Sabiyah site inland from the northern edge of Kuwait Bay. The pearl is pierced through so clearly its intended use was decorative. A number of mother-of-pearl beads, buttons and other kinds of shell jewelry were also found, evidence of the long tradition of pearling in the Persian Gulf.

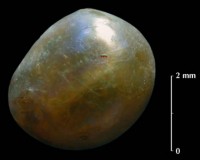

A new study has moved the oldest date of archaeological pearls even further back to approximately 5500 B.C. Researchers with the French Foreign Ministry have found 42 burials in the Neolithic site of Umm al-Quwain 2 in the United Arab Emirates. The burials were spread through four shell layers from different periods alternating with layers of sterile sand. In the earliest shell layer, recently radiocarbon dated to 5500 B.C., a small pearl 0.07 inches in diameter was recovered after excavation from sand stuck to the skull of skeleton/burial 4.

A new study has moved the oldest date of archaeological pearls even further back to approximately 5500 B.C. Researchers with the French Foreign Ministry have found 42 burials in the Neolithic site of Umm al-Quwain 2 in the United Arab Emirates. The burials were spread through four shell layers from different periods alternating with layers of sterile sand. In the earliest shell layer, recently radiocarbon dated to 5500 B.C., a small pearl 0.07 inches in diameter was recovered after excavation from sand stuck to the skull of skeleton/burial 4.

Interestingly, this pearl was not perforated. It wasn’t worn on a string or embroidered onto clothing. Like more recent archaeological pearls discovered placed on the upper lip of a buried skeleton, it appears to have had a ritual role.

Interestingly, this pearl was not perforated. It wasn’t worn on a string or embroidered onto clothing. Like more recent archaeological pearls discovered placed on the upper lip of a buried skeleton, it appears to have had a ritual role.

The pearl is remarkably well preserved, its luster dimmed, perhaps, but not destroyed, thanks to the layers of shell which lowered the pH level of the sand layers. That same mechanism preserved an impressive 18 pearls from 4700 – 4100 B.C. found on the UAE island of Akab. The Akab pearls come in white, pink and orange shades and retain their original luster. Almost all of them are round, which are far less frequently found in nature than the baroque shapes.

French adventurer Henry de Monfreid described going traditional pearl fishing on the Red Sea with four men in 1935. They worked all day and found only 27 pearls in 1000 oysters. Out of that 27, 20 were baroque and five were round ones the size of a pinhead. That means the Neolithic pearl divers, who already were doing an incredibly dangerous and difficult job, discarded the vast majority of the pearls they found in favor of the ones closest to spherical.

French adventurer Henry de Monfreid described going traditional pearl fishing on the Red Sea with four men in 1935. They worked all day and found only 27 pearls in 1000 oysters. Out of that 27, 20 were baroque and five were round ones the size of a pinhead. That means the Neolithic pearl divers, who already were doing an incredibly dangerous and difficult job, discarded the vast majority of the pearls they found in favor of the ones closest to spherical.

It’s amazing to think of how powerful a role pearls played in Neolithic sea-dependent cultures and how far back that goes. They weren’t just objects of great beauty and fragility, prizes to be kept and to inspire trade with Mesopotamian civilizations. They were also symbols used in the most profound rituals surrounding life and death.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell

Ariel’s song, Act 1, Scene 2, The Tempest