After more than a decade of restoration work, Santa Maria Antiqua, one of the earliest and most historically significant Christian churches in Rome, will be open to tour groups by invitation only starting in September of this year, then open to the public at large in 2013. Built out of part of a palace complex on the Palatine dating to the reign of Emperor Domitian (reigned 81-96 A.D.), the building was converted into a Christian church in the sixth century. It was the second Christian church consecrated in the Roman Forum, the religious and political center of the ancient city, and thanks to various sackings and demolitions of later structures, it remains one of only two Christian churches in the Forum today. (The other is Santi Cosma e Damiano, built a few decades before Santa Maria.)

After more than a decade of restoration work, Santa Maria Antiqua, one of the earliest and most historically significant Christian churches in Rome, will be open to tour groups by invitation only starting in September of this year, then open to the public at large in 2013. Built out of part of a palace complex on the Palatine dating to the reign of Emperor Domitian (reigned 81-96 A.D.), the building was converted into a Christian church in the sixth century. It was the second Christian church consecrated in the Roman Forum, the religious and political center of the ancient city, and thanks to various sackings and demolitions of later structures, it remains one of only two Christian churches in the Forum today. (The other is Santi Cosma e Damiano, built a few decades before Santa Maria.)

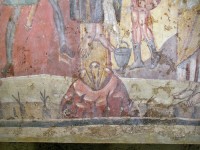

Some of the materials used and style of the paintings are characteristically Byzantine, an unusual approach in the city of Rome, perhaps the product of artists and workshops from the Eastern Empire. Over the next three centuries, the walls were extensively frescoed, with later works sometimes painted over earlier ones. These layered paintings provide unique insight into the development of Byzantine and early medieval art, especially since much Byzantine religious art was destroyed by 8th and 9th century Iconoclasm in the East. Thankfully, Byzantine control over the West was weak by that time. Popes Gregory II and Gregory III rejected Byzantine imperial edicts to destroy all religious art, thus sparing Rome from the wholesale destruction of early Christian art suffered in Constantinople.

Some of the materials used and style of the paintings are characteristically Byzantine, an unusual approach in the city of Rome, perhaps the product of artists and workshops from the Eastern Empire. Over the next three centuries, the walls were extensively frescoed, with later works sometimes painted over earlier ones. These layered paintings provide unique insight into the development of Byzantine and early medieval art, especially since much Byzantine religious art was destroyed by 8th and 9th century Iconoclasm in the East. Thankfully, Byzantine control over the West was weak by that time. Popes Gregory II and Gregory III rejected Byzantine imperial edicts to destroy all religious art, thus sparing Rome from the wholesale destruction of early Christian art suffered in Constantinople.

The earliest painting dates to the middle of the 6th century. It’s known as a Maria Regina because it depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned, wearing a garment festooned with pearls in the style of a Byzantine empress. It’s thought to be the earliest surviving depiction of Mary as Queen of Heaven. It’s on a wall to the right of the apse, and probably was painted before the apse was even finished. On top of her are another six layers of frescoed plaster. Flaking and wear reveal fragments of each layer. This wall is known as the palimpsest wall because of the exposed superimposed layers. The website of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome has a neato Flash applet illustrating the stratigraphy of the palimpsest.

The earliest painting dates to the middle of the 6th century. It’s known as a Maria Regina because it depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned, wearing a garment festooned with pearls in the style of a Byzantine empress. It’s thought to be the earliest surviving depiction of Mary as Queen of Heaven. It’s on a wall to the right of the apse, and probably was painted before the apse was even finished. On top of her are another six layers of frescoed plaster. Flaking and wear reveal fragments of each layer. This wall is known as the palimpsest wall because of the exposed superimposed layers. The website of the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome has a neato Flash applet illustrating the stratigraphy of the palimpsest.

Another notable work is the portraits of medical saints, painted during the early 8th century during the papacy of John VII. Historians believe people came to the chapel to be healed by the images of the saints, a tradition of the Eastern Church instituted in Rome during the Byzantine Papacy (537-752) when all the popes were selected by the Eastern Emperor. When the Roman papacy sought the patronage of Frankish King Pepin instead, Eastern customs fell out of favor. This is one of the only depictions of the medical saint tradition extant.

Another notable work is the portraits of medical saints, painted during the early 8th century during the papacy of John VII. Historians believe people came to the chapel to be healed by the images of the saints, a tradition of the Eastern Church instituted in Rome during the Byzantine Papacy (537-752) when all the popes were selected by the Eastern Emperor. When the Roman papacy sought the patronage of Frankish King Pepin instead, Eastern customs fell out of favor. This is one of the only depictions of the medical saint tradition extant.

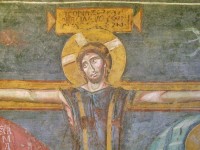

The frescoes in the chapel of Theodotus, named after a wealthy and prominent official at the court of Pope Zaccarias (r. 741-752) whose family is depicted in one of the paintings, are some of the best preserved. Sequences include the Crucifixion, the martyrdom of Quiricus (aka Cyricus) and Julietta, and the Virgin and Christ Child accompanied by Saints Peter, Paul, Julietta and Pope Zaccarias.

The frescoes in the chapel of Theodotus, named after a wealthy and prominent official at the court of Pope Zaccarias (r. 741-752) whose family is depicted in one of the paintings, are some of the best preserved. Sequences include the Crucifixion, the martyrdom of Quiricus (aka Cyricus) and Julietta, and the Virgin and Christ Child accompanied by Saints Peter, Paul, Julietta and Pope Zaccarias.

The church was abandoned in the 9th century after it was damaged by an earthquake and subsequent landslide in 847. In a classic historical paradox, the earthquake that wiped it off the map is probably what saved the frescoes from getting obliterated by war or new architectural fads. A new church, Santa Maria Liberatrice, was built on top of part of the old church in the 13th century. Santa Maria Liberatrice was rebuilt in Baroque style in 1600.

The church was abandoned in the 9th century after it was damaged by an earthquake and subsequent landslide in 847. In a classic historical paradox, the earthquake that wiped it off the map is probably what saved the frescoes from getting obliterated by war or new architectural fads. A new church, Santa Maria Liberatrice, was built on top of part of the old church in the 13th century. Santa Maria Liberatrice was rebuilt in Baroque style in 1600.

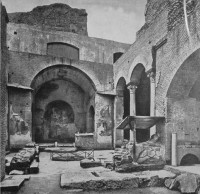

Santa Maria Antiqua was rediscovered again in 1701 by scavengers looking for building material in the Roman Forum. The apse was excavated and became a popular subject for artists and tourists to visit. They only got three months to enjoy the view, however, because the landowner decided to rebury it.

Urban legend has it that it was rediscovered yet again in 1900, when a monk fell into a sinkhole while digging in the vegetable garden. What we know for sure is that in 1900, as new excavations revealed more and more of the Roman Forum around it, the government decided to dispose of that pesky medieval/Baroque church in their way. Archaeologist Giacomo Boni took on the task of destroying history. The old church was so well built it took them two years to take it down. They had to use dynamite in the end, and no, there was no archaeological survey done on the site at any point during those two years.

Urban legend has it that it was rediscovered yet again in 1900, when a monk fell into a sinkhole while digging in the vegetable garden. What we know for sure is that in 1900, as new excavations revealed more and more of the Roman Forum around it, the government decided to dispose of that pesky medieval/Baroque church in their way. Archaeologist Giacomo Boni took on the task of destroying history. The old church was so well built it took them two years to take it down. They had to use dynamite in the end, and no, there was no archaeological survey done on the site at any point during those two years.

Once fully excavated, Santa Maria Antiqua revealed more than 250 square meters (that’s 2690 square feet) of frescoes in brilliant color which of course immediately began to degrade courtesy of exposure to the elements. As excavations in the Forum continued, the church was used as a storage space for ancient artifacts. A wooden roof was built over the central nave in 1910 to try to stop the rapid deterioration.

Once fully excavated, Santa Maria Antiqua revealed more than 250 square meters (that’s 2690 square feet) of frescoes in brilliant color which of course immediately began to degrade courtesy of exposure to the elements. As excavations in the Forum continued, the church was used as a storage space for ancient artifacts. A wooden roof was built over the central nave in 1910 to try to stop the rapid deterioration.

It wasn’t enough. From 1912 until 1957, 12% of the frescoes were detached from the wall, transferred to new supports and kept in the Forum museum. In 1980 the church was closed permanently to the public and conservation work began in situ this time. In 2001, a program of thorough documentation and restoration was begun with funding and collaboration from the World Monuments Fund, among others, and it’s this program that is finally coming to an end. Some of the detached panels have been returned to their original locations.

The portraits of saints, surrounded by images of date trees and improbable fringed curtains, will remain partly unrestored and noticeably eroded.

“It leaves space for imagination,” said Werner Matthias Schmid, a principal conservator for the project, while giving a recent tour of the damp and dimly lighted church. Glaring white patches where paint had peeled away have been toned down to a grayish color. “We diminished the distortions of the losses,” he said.

The conservators have methodically documented their decisions about every millimeter of the restoration, as they stabilized flaking paint and undid failing old repairs. […]

The conservators have found Latin and Greek inscriptions in the murals in addition to traces of ancient brush strokes. The saints’ eyes and pearl strands are formed from dots of white lime. “Up close they’re almost three-dimensional,” Mr. Schmid said.

And now my favorite part: the before and after pics.