The Kunstmuseum Basel reopens on Tuesday, May 12th, allowing visitors to enjoy a little-known aspect of Renaissance art: small-format stained glass paintings created by Old Masters like Hans Holbein the Younger. Very few of these works survive today, but for a brief period in the 16th century they were wildly popular in Switzerland and southern Germany, donated by organizations and prominent individuals to adorn civic buildings, monasteries, churches, universities and guildhalls.

The Kunstmuseum Basel reopens on Tuesday, May 12th, allowing visitors to enjoy a little-known aspect of Renaissance art: small-format stained glass paintings created by Old Masters like Hans Holbein the Younger. Very few of these works survive today, but for a brief period in the 16th century they were wildly popular in Switzerland and southern Germany, donated by organizations and prominent individuals to adorn civic buildings, monasteries, churches, universities and guildhalls.

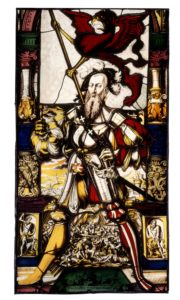

Beyond its immediate artistic appeal, the genre is of great interest in both a historical and a sociocultural perspective. Stained glass paintings were commissioned by institutions such as the estates of the Old Swiss Confederacy (today’s cantons), monasteries, and guilds as well as individuals. Donating such a work was a common and widely recognized act of social communication, lending lasting expression to alliances, friendships, and honors. That is why virtually every stained glass painting prominently features the donor’s coat of arms. The imagery surrounding this central element varies widely and includes depictions of religious themes as well as personifications and allegories, representations of professions, and motifs and scenes from Swiss history.

The Kunstmuseum Basel has more than 20 of these rare stained glass paintings in its permanent collection, and close to 400 of the preparatory drawings used to create the glass pieces. For the Luminous Figures: Drawings and Stained Glass Paintings from Holbein to Ringler exhibition, curators selected 20 of the most significant paintings and 70 preparatory drawings. Other museums — the Victoria and Albert in London, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, and the Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, Zurich — loaned works for the exhibition as well.

The Kunstmuseum Basel has more than 20 of these rare stained glass paintings in its permanent collection, and close to 400 of the preparatory drawings used to create the glass pieces. For the Luminous Figures: Drawings and Stained Glass Paintings from Holbein to Ringler exhibition, curators selected 20 of the most significant paintings and 70 preparatory drawings. Other museums — the Victoria and Albert in London, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, and the Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, Zurich — loaned works for the exhibition as well.

On display are the earliest surviving preparatory drawing for a glass painting (dating to around 1470/80) and striking pen-and-ink prep drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger and other masters. The museum was able to pair up a few of the preparatory drawings with the finished glass paintings, bringing them back together again for the first time in five centuries.

On display are the earliest surviving preparatory drawing for a glass painting (dating to around 1470/80) and striking pen-and-ink prep drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger and other masters. The museum was able to pair up a few of the preparatory drawings with the finished glass paintings, bringing them back together again for the first time in five centuries.

As usual with museum exhibitions, there are a number of associated events on the calendar where people can learn more about stained glass in general and this very specific and localized expression of the medium. One extremely cool event really sets the “luminous figures” in their precise historical and cultural context. It’s a guided tour of Basel Town Hall (built between 1504 and 1514) and the Schützenhaus (the firing range built in the 1560s by Basel’s Riflemen guild that was in continuous use until 1899 and is now a restaurant that I very much want to patronize) which still have their original stained glass paintings in situ.

As usual with museum exhibitions, there are a number of associated events on the calendar where people can learn more about stained glass in general and this very specific and localized expression of the medium. One extremely cool event really sets the “luminous figures” in their precise historical and cultural context. It’s a guided tour of Basel Town Hall (built between 1504 and 1514) and the Schützenhaus (the firing range built in the 1560s by Basel’s Riflemen guild that was in continuous use until 1899 and is now a restaurant that I very much want to patronize) which still have their original stained glass paintings in situ.