The Noceto Vasca Votiva, a large wooden basin discovered in the Po Plain of northern Italy, has been absolutely dated to 1444 B.C. thanks to an innovative combination of tree ring and radiocarbon dating. Previously the date range could only narrowed down to 1600-1300 B.C., and the new precise date places the construction of this monumental pool at a moment of great societal change in Bronze Age northern Italy.

The Noceto Vasca Votiva, a large wooden basin discovered in the Po Plain of northern Italy, has been absolutely dated to 1444 B.C. thanks to an innovative combination of tree ring and radiocarbon dating. Previously the date range could only narrowed down to 1600-1300 B.C., and the new precise date places the construction of this monumental pool at a moment of great societal change in Bronze Age northern Italy.

The structure was discovered in 2004 during construction work on a hill in the south side of Noceto. Digging in the side of the hill revealed a large stratified pit containing fragments of pottery and wooden posts. Subsequent excavations revealed an extraordinary structure that is unique on the archaeological record. It was located at the edge of a Terramare, a Late Bronze Age settlement of a type found in Po Plain. The remains of the settlement are almost completely gone, destroyed by quarrying in the 19th century.

The structure was discovered in 2004 during construction work on a hill in the south side of Noceto. Digging in the side of the hill revealed a large stratified pit containing fragments of pottery and wooden posts. Subsequent excavations revealed an extraordinary structure that is unique on the archaeological record. It was located at the edge of a Terramare, a Late Bronze Age settlement of a type found in Po Plain. The remains of the settlement are almost completely gone, destroyed by quarrying in the 19th century.

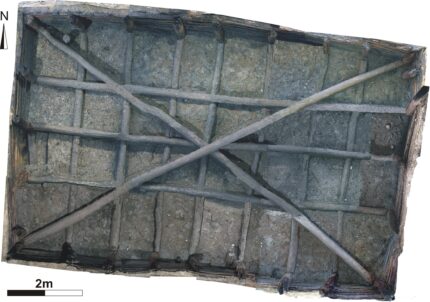

It was built of oak poles, beams and planks and measures about 40 by 23 feet, larger than most home in-ground pools today. The wood-lined tank was also in-ground. The hillside was dug out to make a large pit into which the structure was inset. It was constructed in two phases. The first tank, known as the Lower Tank, collapsed either during construction or right after it. The remains consist of 36 vertical poles planted into the subsoil at regular intervals along a rectangular perimeter. Planks were locked into grooves on the poles to support the pit walls, and at the floor level posts and boards were anchored to posts in the center of the pit and to horizontal beams. Wood shavings and tools were found there indicating the walls, under pressure from the heavy clay soil, collapsed suddenly before it was finished.

It was built of oak poles, beams and planks and measures about 40 by 23 feet, larger than most home in-ground pools today. The wood-lined tank was also in-ground. The hillside was dug out to make a large pit into which the structure was inset. It was constructed in two phases. The first tank, known as the Lower Tank, collapsed either during construction or right after it. The remains consist of 36 vertical poles planted into the subsoil at regular intervals along a rectangular perimeter. Planks were locked into grooves on the poles to support the pit walls, and at the floor level posts and boards were anchored to posts in the center of the pit and to horizontal beams. Wood shavings and tools were found there indicating the walls, under pressure from the heavy clay soil, collapsed suddenly before it was finished.

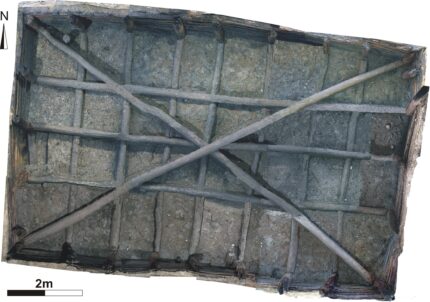

The second tank, known as the Upper Tank, was built on top of it. Some of the Lower Tank’s wood was recycled into the Upper, but the design, shape and size were altered to correct the flaws that caused the first tanks demise. Much more of the Upper Tank survives, preserved for millennia in the anoxic environment created by layers of sediment, peat and rainwash. It consists of 26 vertical poles along the rectangular perimeter. The poles hold almost 250 horizontal beams that slightly overlap each to create a strong interlocking structure. Beams crisscross the base of the rectangle, first across its width, then across it length. They are reinforced by two long beams that cross the tank on the diagonal to act as supports for the four corner poles.

The second tank, known as the Upper Tank, was built on top of it. Some of the Lower Tank’s wood was recycled into the Upper, but the design, shape and size were altered to correct the flaws that caused the first tanks demise. Much more of the Upper Tank survives, preserved for millennia in the anoxic environment created by layers of sediment, peat and rainwash. It consists of 26 vertical poles along the rectangular perimeter. The poles hold almost 250 horizontal beams that slightly overlap each to create a strong interlocking structure. Beams crisscross the base of the rectangle, first across its width, then across it length. They are reinforced by two long beams that cross the tank on the diagonal to act as supports for the four corner poles.

All of this took an enormous amount of work and determination to accomplish. Excavating the hillside, removing tons of soil, dragging the oak timbers to site and building the tank not once but twice underscores how important it was to the builders. Sediment analysis found that the once completed, the Upper Tank was filled with water.

All of this took an enormous amount of work and determination to accomplish. Excavating the hillside, removing tons of soil, dragging the oak timbers to site and building the tank not once but twice underscores how important it was to the builders. Sediment analysis found that the once completed, the Upper Tank was filled with water.

Its location at the top of the hill was too inconvenient for a cistern. There are no channels as there would be if it was used for irrigation. Archaeologists unearthed a large quantity of depositions: about 150 whole vases, 25 miniature vessels, seven clay figurines, plus baskets, handles, spindles, shovels and wooden plow parts. They were not haphazardly strewn into the tank, but carefully lowered into it in at least three separate deposition events. This indicates the tank was used for ritual purposes.

The exact dates of the tanks was pinpointed by a team from Cornell University’s Tree-Ring Laboratory using 28 wood samples, nine from the Upper Tank, 19 from the Lower Tank.

Among the lab’s specialties is tree-ring sequenced radiocarbon “wiggle-matching,” in which ancient wooden objects are dated by matching the patterns of radiocarbon isotopes from their annual growth increments (i.e., tree rings) with patterns from datasets found elsewhere around the world. This enables ultra-precise dating even when a continuous tree-ring sequence for a particular species and geographic area is not yet available.

“Working at an archaeological site, you’re often trying to do dendrochronology with relatively few samples, sometimes in less than ideal condition, because they’ve been falling apart for the last 3,500 years before you get to see them. It’s not like a healthy tree that is growing out in the wild right now,” Manning said. “We often measure the samples a number of times to extract as much signal as we can.” […]

Manning’s team made multiple attempts with different samples. While the wood from the Noceto site was well-preserved – a rarity, given its age – there was an unexpected challenge when the samples did not seem to fit the international radiocarbon calibration curve that is used for matching tree-ring sequences. This suggested the curve needed revising for certain time periods, and in 2020 a new version was published. The Noceto data finally fit.

By combining radiocarbon dating calibrated via dendrochronologies from southern Germany, Ireland and North America, along with computer-intensive statistics, the Cornell team was able to establish a tree-ring record that spanned several hundred years. They pegged the construction of the lower and upper tanks at 1444 and 1432 B.C., respectively; and they determined the finished structure was in use for several decades before it was abandoned, for reasons that may never be known.

The new timeline is particularly significant because it synchs up with a period of enormous change in Italian prehistory.

“You’ve had one way of life in operation for hundreds of years, and then you seem to have a switch to fewer, larger settlements, more international trade, more specialization, such as textile manufacture, and a change in burial practices,” Manning said. “There is something of a pattern all around the world. Nearly every time there’s a major change in social organization, there tends often to be an episode of building what might be described as unnecessary monuments. So when you get the first states forming in Egypt, you get the pyramids. Stonehenge marks a major change in southern England. Noceto is not the scale of Stonehenge, but it has some similarities – an act of major place-making.”

The study has been published in the journal PLoS ONE and can be read in its entirety here.

Excavation of a necropolis in the ancient Roman town of Boutae, near Annecy is southeastern France, has yielded rich Germanic funerary furnishings. Radiocarbon dating and analysis of the artifacts dates the necropolis to between the second half of the 5th century and the second half of the 7th, indicating there was a stable population of Burgundians living in Boutae after the establishment of the First Kingdom of Burgundy in the Rhineland and Savoy in 443.

Excavation of a necropolis in the ancient Roman town of Boutae, near Annecy is southeastern France, has yielded rich Germanic funerary furnishings. Radiocarbon dating and analysis of the artifacts dates the necropolis to between the second half of the 5th century and the second half of the 7th, indicating there was a stable population of Burgundians living in Boutae after the establishment of the First Kingdom of Burgundy in the Rhineland and Savoy in 443. Roman roads and on the Alpis Graia, the route leading to the Petit Saint-Bernard alpine pass, Boutae prospered under the Roman Empire. It was razed and much of the population killed in the Germanic invasions of the mid-3rd century, but it was rebuilt in the 3rd century. The vicus was largely abandoned in the early 5th century in the wake of the Burgundian invasion, but some of pockets of the town were used until the end of the 7th century.

Roman roads and on the Alpis Graia, the route leading to the Petit Saint-Bernard alpine pass, Boutae prospered under the Roman Empire. It was razed and much of the population killed in the Germanic invasions of the mid-3rd century, but it was rebuilt in the 3rd century. The vicus was largely abandoned in the early 5th century in the wake of the Burgundian invasion, but some of pockets of the town were used until the end of the 7th century. documented until last year. INRAP archaeologists explored almost half an acre and unearthed 227 graves, a fraction of the total burials at the site. There are a variety of grave types including wooden coffins, hollowed out trunks, sandstone slabs. Thirty of the graves contained high quality furnishings, either worn by the deceased or placed in the pit. Their decorative style mark the grave goods as Burgundian.

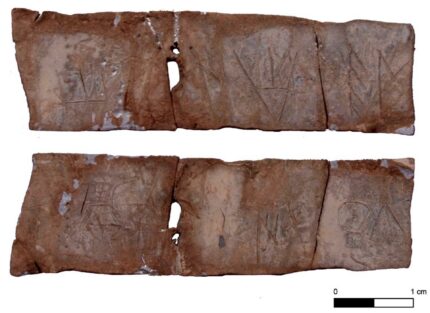

documented until last year. INRAP archaeologists explored almost half an acre and unearthed 227 graves, a fraction of the total burials at the site. There are a variety of grave types including wooden coffins, hollowed out trunks, sandstone slabs. Thirty of the graves contained high quality furnishings, either worn by the deceased or placed in the pit. Their decorative style mark the grave goods as Burgundian. Most of the objects are objects of adornment or grooming. There are a dozen decorated bone combs, glass beads on necklaces and châtelaines, belt buckles, shoe buckles, a three-piece toiletry kit, a silver gilt fibula shaped like a bird of prey with a garnet eye and a matched set of fibulae in the shape of galloping horses. Only two weapons were found: an arrowhead and a scramasax with a fragment of its wooden scabbard still attached.

Most of the objects are objects of adornment or grooming. There are a dozen decorated bone combs, glass beads on necklaces and châtelaines, belt buckles, shoe buckles, a three-piece toiletry kit, a silver gilt fibula shaped like a bird of prey with a garnet eye and a matched set of fibulae in the shape of galloping horses. Only two weapons were found: an arrowhead and a scramasax with a fragment of its wooden scabbard still attached.